Digitizing Việt Nam marks a digital leap forward in Vietnam Studies through a Columbia - Fulbright collaboration, formalized through that began with a 2022 memorandum of understanding between the Weatherhead East Asian Institute and the Vietnam Studies Center. The Digitizing Việt Nam platform began with the generous donation of the complete archive by the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation to Columbia University in 2018.

Delve into Vietnam's history, culture, and society through cutting-edge tools and curated resources tailored for scholars, students, and educators.

Explore our digital archive dedicated to preserving and academically exploring Vietnam's historical, cultural & intellectual heritage.

Engage creatively with Vietnam Studies — Use Digitizing Vietnam's specialized tools to approach the field with fresh perspectives and critical insight.

Discover and teach Vietnam Studies with impact — Explore curated syllabi, lesson plans, and multimedia resources designed to support innovative and inclusive learning experiences.

Latest news and discoveries from the digital front of Vietnamese heritage.

Columbia University Libraries proudly unveils the Vietnamese Hán-Nôm Digital Collection, an exceptional digital archive of approximately 1,100 rare and invaluable texts drawn from the Hán-Nôm holdings of the National Library of Vietnam, Thắng Nghiêm Temple (Hà Nội), and Phổ Nhân Temple (Hưng Yên).

At the heart of this collection is a remarkable preservation effort led by the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation (VNPF), which, together with the National Library, digitized these works to safeguard Vietnam’s literary and intellectual heritage. Spanning the premodern to early modern eras, the texts illuminate a vast spectrum of knowledge, from literature, history, and geography to religion, medicine, musicology, folklore, and general science, all recorded using the Hán - Nôm script.

Following VNPF’s completion of its mission and dissolution in 2018, the collection was acquired by Columbia University Libraries in 2021. Today, the Libraries steward the archive in collaboration with the Digitizing Việt Nam Project, an ongoing initiative carried out by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University in collaboration with the Vietnam Studies Center at Fulbright University Vietnam, dedicated to supporting access, tools, and scholarship for students and researchers of Vietnamese studies worldwide.

View the collection here: https://dlc.library.columbia.edu/npf_vietnamese

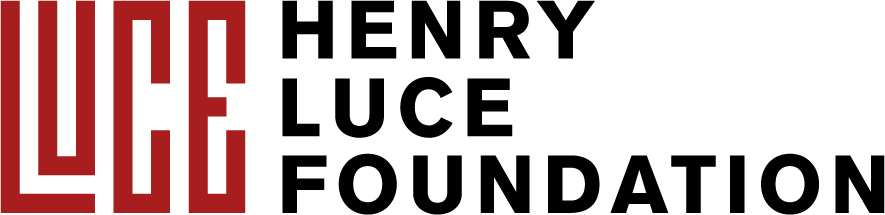

English-language scholarship has too often reduced South Vietnam to a mere American fabrication, portraying it as little more than an outgrowth of U.S. imperialism. As another title amongst the series Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University, Republican Vietnam, 1963–1975: War, Society, Diaspora (University of Hawaii, 2025), edited by Trinh M. Luu and Tuong Vu, decisively challenges this view by revealing the Second Republic as a diverse, dynamic, and internally driven society. Across twelve essays grounded in original archival research, the volume reconstructs the Second Republic in all its complexity, showing how politicians, students, educators, publishers, journalists, musicians, religious leaders, businesspeople, and ordinary citizens together forged a richly layered social world. This society was marked by remarkable entrepreneurial energy, a combative and outspoken press, globally connected religious institutions, a vibrant intellectual and associational life, and a level of artistic production unparalleled since the Vietnam War.

Although this period was brief, its intensity and creativity fostered a resilient republican spirit that Vietnamese refugees later carried into exile. The abundant legacy of vernacular music, print culture, and the many associations established by the Vietnamese diaspora attest to the republican values that once animated South Vietnamese life. Yet despite this complexity, popular media and much American scholarship have continued to depict South Vietnam as a fundamentally dependent polity, ruled by corrupt leaders beholden to U.S. interests. Against such reductive portrayals, this volume places South Vietnamese actors at the center of their own history, emphasizing their agency, aspirations, and struggles.

Republican Vietnam is the first scholarly collection devoted to the Second Republic to appear since the end of the Vietnam War, and among the earliest to employ republicanism as an analytical lens for reexamining twentieth-century Vietnamese history, the war itself, and the Vietnamese diaspora. Taken together, the essays demonstrate how warfare, intertwined with foreign intervention, shaped South Vietnam’s economy, culture, and the everyday lives of individuals and families. By bringing together scholarship from both Vietnam-based and diasporic studies, the volume bridges two fields that have long developed in parallel, laying essential groundwork for future cross-disciplinary research.

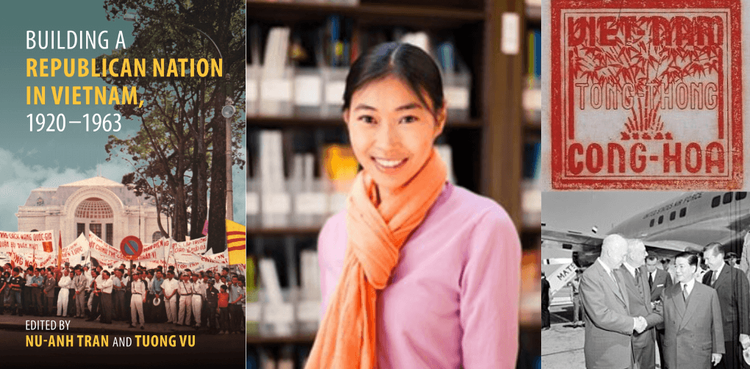

Western observers have long treated communism as synonymous with Vietnam’s modern historical experience. Seeking to explain North Vietnam’s victory in the Vietnam War, scholars and journalists have devoted extensive attention to the history of the Vietnamese communists. This focus, however, has obscured the diversity of ideas and lived experiences that shaped twentieth-century Vietnam, in which communism was only one among many political currents. Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963, edited by Nu-anh Tran and Tuong Vu, argues that republicanism influenced modern Vietnam no less profoundly than communism. Republicans championed representative government, universal human rights, civil liberties, and the primacy of the nation. These ideas permeated the thinking of Vietnamese reformers, dissidents, and revolutionaries from the early 1900s onward, including many men and women who later led the struggle for independence. Republicanism also served as a major intellectual foundation for the establishment of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) in 1955.

Belonging to the series Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University, this interdisciplinary volume (University of Hawaii Press, 2023) brings together eleven essays by historians, political scientists, literary scholars, and sociologists who draw on newly available sources to examine the development of republicanism from the colonial era through the First Republic of Vietnam (1955–1963). In their introduction, coeditors Nu-Anh Tran and Tuong Vu critically reassess the existing scholarship on the First Republic, demonstrate how republicanism sheds new light on political developments in the Saigon-based state, and situate the regime in comparative perspective with South Korea. Peter Zinoman’s chapter surveys the historiography of republicanism and modern Vietnam and signals the emergence of a “republican moment” in Vietnam studies. Essays by Nguyễn Lương Hải Khôi, Martina Thucnhi Nguyen, and Yen Vu trace the transformation of republican ideas over time. Nu-Anh Tran and Duy Lap Nguyen analyze competing conceptions of democracy and the factional politics of the First Republic. Contributions by Jason Picard, Cindy Nguyen, Hoàng Phong Tuấn, Nguyễn Thị Minh, and Y Thien Nguyen explore nation- and state-building efforts in the 1950s and 1960s. Taken together, the essays recover the voices of Vietnamese republicans—from the ideas they articulated and the institutions they created to the political legacies they left behind.