Hồ Xuân Hương’s title as “The Queen of Nôm Poetry” (a phrase coined by poet Xuân Diệu) perhaps best reflects the immense influence and rebellious force of her verse. Born around 1772, at the end of the Lê dynasty (which lasted from 1592–1788), she is thought to have been the daughter of Hồ Sĩ Danh (1706–1783) or Hồ Phi Diễn (1703–1786), and the child of a concubine. Because of her social position, she likely did not receive the same formal education as men or royal women. Yet she composed poetry in both classical Chinese and Nôm (Vietnamese demotic script)—around 150 poems are recorded—and became especially renowned for her Nôm works.

Instead of adhering to rigid conventions, allusions, and classical references typical of Sino-cultural poetry, Hồ Xuân Hương’s choice to write in Nôm—the vernacular language of everyday life—freed her from Confucian literary constraints, allowing her to speak with a distinct personal voice. Her inspiration sprang from the most ordinary experiences: “a betel quid,” “a floating cake,” “a jackfruit on a tree,” “a snail’s lot,” “a patch of foul grass,” and even more abstract expressions like “the beauty” (in Self-Lament). One of her special talents lies in expressing delicate or elusive ideas through earthy, colloquial imagery.

As noted in The Annotated Nôm Dictionary (edited by Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng), the word cái (丐) has multiple meanings: it can designate an object, mark femininity (in contrast to masculinity), mean “mother,” or refer to something greater (as in “trống cái” – the main drum, “đường cái” – main road). Meanwhile, hồng nhan (紅顔, literally “rosy face”) evokes a more elusive sense—perhaps a beautiful young woman, perhaps destiny or romance (since hồng can mean both “red” and “fate”). When combined as cái hồng nhan, femininity is embodied yet impossible to define precisely—a poetic tension between presence and abstraction.

Although her poem titles often suggest still scenes or quiet objects—“The Jackfruit,” “Autumn Scene,” “The Snail,” “The Floating Cake,” “The Crab”—each line is full of motion. Hồ Xuân Hương’s poetry does not merely describe things as static objects but speaks through them, claiming agency even in seemingly modest tones:

“My body is white, my fate is round” (The Floating Cake)

“My body is like a jackfruit on the tree” (The Jackfruit)

“I wear a green tunic, a yellow bodice / Three soldiers carry my palanquin, high and proud” (The Crab)

Her verbs dominate the verse, imbuing it with a sense of vitality and rhythm. Sometimes action even precedes the subject, creating a world brimming with energy and embodiment:

“Green wraps the tree trunk with a rounded crown,

White spreads across the calm, silent stream.” (Autumn Scene)

The movement in Hồ Xuân Hương’s poetry also resides in her layered wordplay. She was a master of “đố tục giảng thanh” (using the vulgar to express the pure) and “đố thanh giảng tục” (using the pure to express the vulgar)—fusing the sacred and profane through clever double meanings. It was this semantic dynamism that gave her poetry such vitality. Drawing from familiar natural and domestic imagery, she hinted at erotic and reproductive themes:

“The white bridge, two planks joined as one,

Clear water flows straight below!

Wild grass curls along the edges,

Tiny fish dart through the stream.”

In a Confucian society where female chastity defined virtue and sexuality was taboo, such multi-layered verses became subtle acts of resistance against moral repression. Yet Hồ Xuân Hương’s poetry transcends the simple dichotomy of sacred and profane. Its multiple layers often reflect broader social, religious, and even national questions—as seen in the word nước non (“water and mountains”) in The Floating Cake, linking personal fate to the destiny of the homeland and its folk roots.

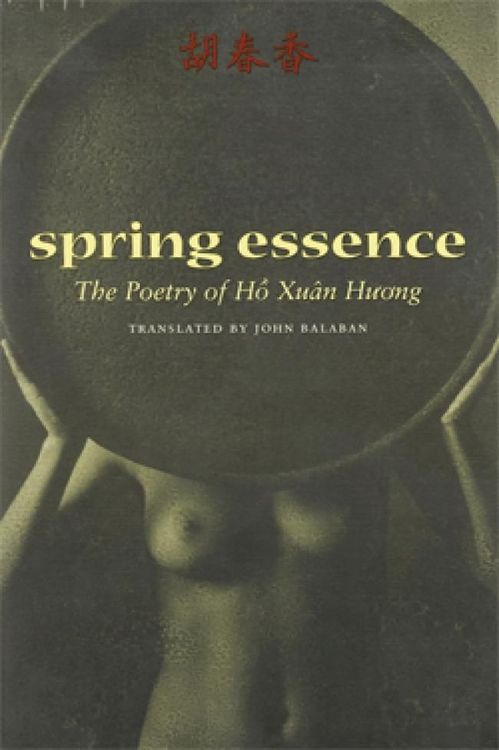

Image source: Works by Nguyen Quoc Thang and Nghiem Nhan, published on VOV.