The Han-Nom Heritage from the Perspective of Philological Studies

There is an urgent need for those working in the field of Hán-Nôm studies to rethink their theoretical approaches and deepen their understanding of the objects they manage and research. Only in this way can a scientific foundation be established to guide, structure, and organize large-scale scientific activities, as well as specific projects and tasks.

In addressing this issue at the outset, we will not explore all aspects and details. Instead, we will focus on the methodology of literary studies, informed by the observable realities in our country. Our goal is to establish broad, essential perspectives on the Hán-Nôm heritage, contributing to the direction and visualization of scientific activities based on Hán-Nôm materials, a vital component of the nation's overall literary heritage.

Cultural heritage in general of a nation or country can encompass many different components and types, from material culture to spiritual culture, from tangible to intangible culture. Among the treasures of the intangible and, potentially, tangible spiritual cultural heritage of a nation, the heritage that carries a literary nature holds an important position.

Hán-Nôm Heritage in the Overall Literary Heritage of the Vietnamese People

Philology, as understood in contemporary science, is the entirety of statements created by humans using language. Once completed and shaped in some way, each statement is referred to as a literary work (shortened to "literature"). Depending on how the material is shaped, literature can be divided into different forms: spoken literature, handwritten literature, printed literature, etc.

When a nation has not yet developed its own writing system for its language and has not borrowed the writing system of another nation, all of its literary works are purely oral. In such a case, its literary heritage can only be oral literature (such as proverbs, folk sayings, ballads, anecdotes, etc.). However, once that nation learns to use writing—whether developing its own or borrowing from another nation—to create written works, that is, texts (văn bản - in the original sense of the word), the spiritual culture of that nation begins to enter a new phase, a phase of having a written tradition (văn hiến - also in the original sense of the term).

It is also important to note that literary works in a nation's literary heritage, whether oral or written, can be created and exist independently (such as proverbs, riddles, folk songs, books, documents, letters, etc.), but they can also accompany other forms of cultural heritage (for example, songs in folk traditions, literary essays, poems, couplets, inscriptions on steles, bells, towers, temples, palaces, etc.).

From the above understanding of literary heritage in general, looking at the practical use of language and writing in Vietnam, we can easily observe that in the entire literary heritage of our country, all types of literature mentioned above are present, including rich and diverse oral literature treasures, as well as collections of texts in Hán characters, Nôm script, Quốc ngữ (Vietnamese alphabet), and many other scripts of different ethnic groups, written by hand and reproduced by manual methods (mainly engraving and woodblock printing), created and passed down by generations of the Vietnamese people.

In terms of types of language and script, the written literary heritage of our country can be differentiated in two steps as follows:

Of course, it is possible that some works may simultaneously use several different languages and writing systems. For example, in the current collection of books at the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies in Hanoi, there are many works of the "phonetic explanation" and "interpretation" types that translate from Hán into Nôm and even into Quốc ngữ (Vietnamese alphabet), French, etc. For such texts, they must be distinguished and handled specifically depending on the degree and nature of the integration or alternation between the different scripts.

The distinction of the written literary heritage in our country based on the criteria of language and writing systems, as outlined above, is certainly not a purely formal procedure. In fact, it reflects very important historical and cultural factors. In the first step, when differentiating between texts written in the Latin alphabet (A) and those written in other systems (B), we are also broadly distinguishing between texts that emerged in modern times as a result of contact with Western civilization (Europe) and those that were created through interaction with Eastern civilization (Asia), which has been closely linked to the long history of the Vietnamese people from ancient times through the medieval period and into the early decades of the 20th century. In the second step, when distinguishing between texts in the square scripts (Han characters) (B1) and other non-Latin scripts that are not square scripts (B2), we are also recognizing the relationship between this classification and the two distinct cultures the Vietnamese people have absorbed: Chinese civilization (for B1) and Indian civilization (for B2).

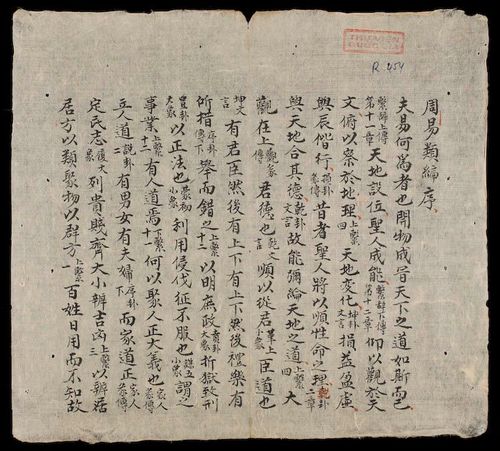

At this point, the theoretical understanding of Hán-Nôm Heritage from a literary perspective has become relatively clear. It consists of written works created or contributed to by the Vietnamese people, primarily based on the ancient Han script and the scripts of the Vietnamese people from the square script system (including various types of Nôm). These texts were shaped and reproduced using manual methods (handwriting, carving, woodblock printing, etc.), forming an important part of the overall written heritage of the Vietnamese people.

Regarding the actual collection of Hán-Nôm texts we currently have, the theoretical framework mentioned above is appropriate and encompasses most of the phenomena that are considered Hán-Nôm heritage. Of course, there may be some exceptional cases where the formation and transmission of texts carry special "fates."

Hán-Nôm heritage is primarily a cultural and historical category. Therefore, not every text or phenomenon involving Hán or Nôm characters is considered Hán-Nôm heritage. The definition presented above excludes certain Hán-Nôm phenomena, mainly referring to texts in Han and Nôm that were written by contemporary Vietnamese people in particular circumstances (and possibly even by foreigners writing about Vietnam). Even though these Hán-Nôm texts may not hold inherent literary value from a purely literary perspective, they still may be important. Thus, when necessary, the concept of "Hán-Nôm Heritage" must be distinguished from all general Hán-Nôm phenomena. However, this distinction is not intended to exclude anything from our scope of management and study; rather, it serves to help us process Hán-Nôm materials more appropriately in our collection and research efforts.

2. Hán-Nôm Literature and Classical Vietnamese Literature

As we have outlined above, Hán-Nôm heritage is an important component of the overall literary heritage of the Vietnamese people. Engaging with Hán-Nôm heritage also means engaging with the intellect and heart of countless generations of our ancestors across almost every aspect of life in our society in the past. Therefore, Hán-Nôm heritage and Hán-Nôm materials can simultaneously serve as objects of study for many different scientific fields. Through Hán-Nôm materials, researchers in fields such as philosophy, history, ethnology, sociology, geography, agriculture, biology, medicine, mathematics, etc., can find essential information, key evidence, and suitable subjects for their research. However, first and foremost, alongside the interest of specialists in these various fields (from social sciences to natural sciences), Hán-Nôm materials need to be processed through the scholarly lens of researchers in the field of Classical Vietnamese Literature.

Philology, as understood today, is the science that studies all linguistic phenomena in all their forms of expression, and the dialectical-historical relationship between the formal elements and the content of literary works.

Here, we will not delve into all aspects of this definition but will highlight a few key points: First, one should avoid the tendency to focus solely on literary works: literary studies are concerned with all forms of language, including scientific language, official documents, letters, books, records, news, etc. Second, the science of philology does not delve into the specialized content values transmitted by language (as this is the task of other scientific fields) but primarily focuses on the linguistic and written aspects of language, including the interpretation of semantic content in its dialectical and historical relationship with the formal elements (language, script, and modes of representation) of the text.

Sometimes, people simplify the notion of literary studies as merely a shorthand or combination of linguistics and literature. In reality, the scope of the term "literary studies" (from the Greek philologié) has varied throughout the history of science from ancient times to the present. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that this term began to be associated not only with linguistics (as 19th-century philologists imagined) but also with the study of literature. It is important to note that the reason literary studies remain within the scope of philology is not because they focus on the artistic nature or the intellectual-aesthetic content of a work (which is more appropriate to the field of art sciences), but because they primarily concern the linguistic and written aspects of the work, the material in words and characters shaped by the hand of the author—the literary artist. It is at this second level that literature is closely related to linguistics, which forms the core of literary studies in general. However, while literature examines and describes artistic works and their aesthetic qualities, linguistics still primarily focuses on linguistic units and their systems as tools for expressing human thought and communication across all fields of social activity. Although linguistics (and related fields like paleography) occupies a very important position, it cannot replace or fulfill all the tasks assigned to other specialized areas of literary studies, such as textual criticism, bibliology, etc., which focus on the texts themselves, including works from all fields.

From the general perspective of literary studies outlined above, let's return to the Hán-Nôm heritage of our country. It is indeed a highly rich and diverse object of study for the classical Vietnamese literature field. Based on the demands of our ideological-cultural revolution and the scientific-technological revolution, in accordance with the objective laws of the development of social sciences, from the Hán-Nôm material treasure, we can establish a series of specialized literary studies that focus on Hán-Nôm phenomena with different subjects and tasks. Aside from what already falls under the scope of historical linguistics or classical Vietnamese literature, which are well known, we believe that within the domain of Hán-Nôm literary studies, three prominent subfields stand out:

(1) Hán-Nôm Paleography: This involves the study of Chinese characters and especially Nôm characters in the Hán-Nôm texts of the Vietnamese people. It looks into the history of their formation and development, describes and compares these Nôm systems, and establishes connections between them and other square-script systems in the region. This field addresses theoretical and technical issues in compiling Han and Nôm dictionaries, creating Hán-Nôm reference materials according to the square-script systems, and more.

(2) Hán-Nôm Textual Studies: This field comprehensively studies the history and preservation of Hán-Nôm texts. It investigates both general issues and specific ones related to the formation, reproduction, preservation, and transmission of Hán-Nôm texts. It may involve in-depth research on the texts of a particular work or the works of a particular author, or a range of works and authors from the same period or from different historical periods. It addresses general and specific issues in dealing with Hán-Nôm texts (such as authentication, editing, annotation, transliteration, and translation) for the purposes of publication and use.

(3) Hán-Nôm Bibliography: This area focuses on classifying and systematizing Hán-Nôm texts and works. It identifies the characteristics of each text type, both in terms of content and form. It examines and establishes methods for text systematization. It addresses general and specific issues in constructing collections of texts and works, Hán-Nôm reference tables, and more. This is the field that inherits traditional bibliography and cataloging, while also laying the foundation for modernizing (including computerizing) Hán-Nôm documentary information work.

Thus, each of the aforementioned subfields has its own distinct research subjects and tasks, and within each subfield, one can delve into different aspects. This defines the trend of specialization for researchers in the field of Hán-Nôm studies. On the other hand, Hán-Nôm literary studies subfields are not, and cannot be, completely isolated from one another. They are always closely interconnected and support each other. This close relationship between the subfields of Hán-Nôm literary studies is not only evident when conducting basic research but also in the design and implementation of applied projects such as the compilation of reference books (for example, creating reference tables for texts and works, authors, compiling Han and Nôm dictionaries, vocabulary collections for personal names, place names, official titles, honorifics in Hán-Nôm materials, etc.) and in constructing collections and anthologies of works, as well as in the annotation, transliteration, translation, and introduction of Hán-Nôm works. These projects often reflect a comprehensive integration of research achievements from multiple specializations within the Hán-Nôm field, as well as achievements from other scientific disciplines (not only in the social sciences and humanities but also in natural sciences and technology).

No scientific discipline can emerge and develop in isolation, fully closed off from other fields of science, both domestically and globally. The field of Hán-Nôm literary studies is no exception to this general scientific rule. Scholars of Hán-Nôm literary studies cannot avoid being influenced by and incorporating the achievements and methods of other scientific fields, particularly history (both Vietnamese and Chinese history), linguistics (the history of Vietnamese and Chinese languages), and all necessary knowledge regarding the historical and cultural relationships between the peoples of the region. It should be emphasized that due to the prominence of Chinese civilization in East Asia during ancient and medieval times, Chinese characters and Classical Chinese (literary Chinese) have been present in the classical literary traditions of many peoples in the region. This has posed common issues for classical literary studies in many countries in the region (Vietnam, North Korea – South Korea, Mongolia, Japan, etc.), which requires us to pay attention to and contribute to research in this area. Additionally, scholars of Hán-Nôm literary studies must regularly engage with and equip themselves with necessary knowledge of general literary studies, as well as theories of paleography, textual studies, bibliography, information studies, etc., depending on their specific specialization. Conversely, through their continuous efforts in their specialized field and their engagement with other scientific disciplines, scholars of Hán-Nôm literary studies can also make significant contributions to the achievements and progress of related scientific fields. Here, there is nothing that prevents a talented scholar of Hán-Nôm literary studies from simultaneously being an expert in other scientific areas.

As presented in the introduction of this article, the Hán-Nôm heritage is a key part, but not the entirety, of the literary heritage of the various ethnic groups in Vietnam. Therefore, while Hán-Nôm literary studies are foundational, they still do not encompass the whole of classical Vietnamese literary studies. To have a comprehensive understanding of classical Vietnamese literary studies, we need a team of scholars who specialize in studying other literary heritages from various ethnic groups across our country, particularly ancient texts written in scripts that are neither part of the square character Han system nor the Latin script, such as the classical scripts of the Thai, Cham, and Khmer peoples in Vietnam, etc. It must be recognized that researching these ancient script collections is not only consistent with the internal logic of the development of literary studies in our country but, first and foremost, is an urgent demand in the implementation of our state's ethnic and cultural policies.

Thus, alongside the Hán-Nôm heritage, classical Vietnamese literary studies also have another rich and diverse research subject. However, the general overview of the scientific subfields within the study of these ancient scripts can still be conceptualized in a manner similar to the way we have described Hán-Nôm heritage. That is, we also identify prominent subfields such as paleography, textual studies, and bibliology, etc. The key difference from Hán-Nôm literary studies is that when engaging with the collections of texts in ancient Thai, Cham, Khmer scripts, etc., we are simultaneously encountering entirely different forms of language and writing systems, which are rooted in the cultural and historical relationships between the ethnic groups of our country and neighboring countries in the region, from the west of the Annamite Range to India. This is where one of the world's most brilliant ancient and medieval civilizations was born, alongside those of Egypt, Greece, and China—the Indian civilization, with its Sanskrit writing system.

Footnotes:

This article by Professor. Nguyễn Quang Hồng was published in Hán Nôm Journal No. 2, Hanoi, 1987, and later reprinted in the book Hán Nôm Journal – 100 Selected Articles by the Institute of Hán Nôm Studies, Hanoi, 2000, as well as in a few other anthologies. We have obtained permission from the author to reprint it on the website Digitizing Vietnam.

(1) See Ju. V. Rozhdestvensky, Vvedenie v obshuju filologiju (Introduction to General Philology), "Vyshaja shkola" Publishing, Moscow, 1979 (in Russian).

(2) It is also possible that some ethnic nationalities in this region may have independently created their own scripts without clear influence from any specific culture, though such cases are very rare. See I.J. Gelb, A Study of Writing, "Raduga" Publishing, Moscow, 1982, p. 258, note 30 (in Russian).

(3) An interesting example of this type is the Hán văn Hồng Nghệ An phú written by revolutionary Lê Hồng Phong while he was imprisoned in Côn Đảo. Lacking paper and pen, Lê Hồng Phong composed it by thinking of each line and reciting it aloud for another prisoner to memorize according to the Hán-Việt pronunciation. Over 40 years later, the comrade transcribed the entire text for Cụ Thạch Can to record in Quốc ngữ and publish in Hán Nôm Studies Journal, No. 1, 1985.

(4) The general spirit derived from Professor Ju. V. Rozhdestvensky’s views on philology (in the referenced work) form the basis for the definition of literary studies presented here.

(5) The term "classical" here does not oppose "modern" but refers to the subject of research: texts and literary works formed in the past and transmitted to the present.

(6) The term thư tịch học (bibliology) may not be entirely suitable, as this term (which is closely associated with the concept of books) does not encompass all the different types of texts and research tasks being considered here.