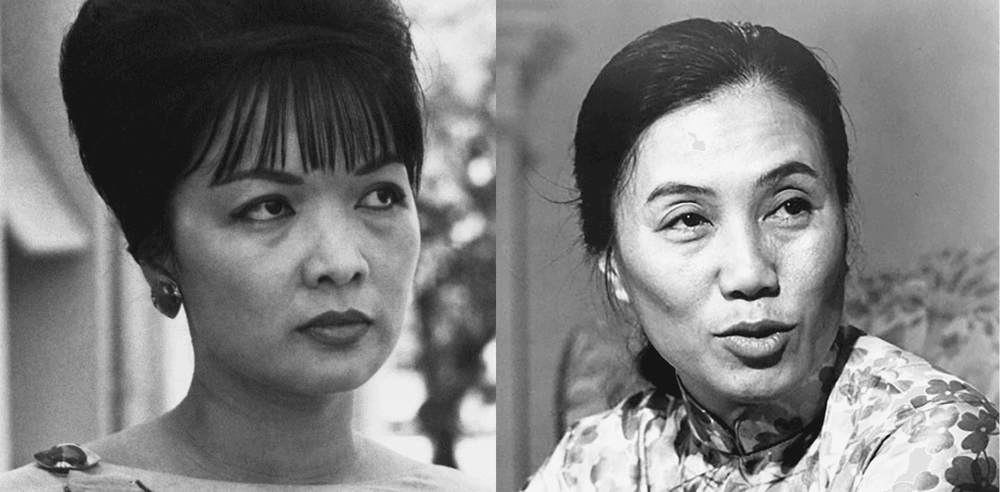

High-level Vietnamese Women Leaders & the Human Factor in the Vietnam War

Both Mdm. Nhu and Mdm. Bình successfully rose to high positions of power at a time when Vietnam was swept by significant political turmoil and women leadership was scarce. Having been educated in French schools,[i][ii] they were part of the small minority of literate women in Vietnam at a time when over ninety-five percent of the population was illiterate,[iii] well-positioning them for future ascendancy. Although they came from privileged backgrounds, their rise to power in the later years were drastically different. Mdm. Nhu became the most powerful woman in South Vietnam chiefly due to her marriage to Ngô Đình Nhu, whereas Mdm. Bình rose the ranks in the Communist leadership because of her work as a cadre in a revolutionary organization. However, that is not to say that Mdm. Nhu did not help secure the Ngô-Đình family’s hold on power, while Mdm. Bình also benefited from her family relations, particularly the fact that she was the granddaughter of Phan Châu Trinh, a revered figure in Vietnamese history.

Trần Lệ Xuân’s rise to the top of the RVN

Trần Lệ Xuân was born into a powerful family and married into power. She belonged to a landowning family whose fortune came from serving the French and Japanese colonial governments. Her father was the eldest son of the Governor-General of Nam Định province, the largest province in North Vietnam, while her mother was a Princess of the Nguyễn dynasty. At the age of eighteen, she married her life partner Ngô Đình Nhu, the younger brother of Ngô Đình Diệm. In an interview with Time magazine, Trần Lệ Xuân confessed that her marriage to Nhu was not borne out of love but was simply a practical matter, given their families’ similar social standing.[iv] Nonetheless, it later served as the golden ticket for her rise to power. After the 1955 State of Vietnam referendum was passed, leading to the creation of the Republic of Vietnam, Diệm proclaimed himself to be the President of the newfound republic, and Mdm. Nhu’s family consequently moved into the Presidential Palace. There, Diệm chose her to be the de facto First Lady of South Vietnam since he was a lifelong bachelor but also because she was a real socialite, making her the perfect hostess. As someone with social graces and a pretty smile, she easily gained the favor of important women in power from other countries and attracted attention from the public due to her flamboyance. In 1956, she was also elected to the RVN National Assembly though the election was not free and fair since the rules imposed by the Presidential Palace hindered opponents of Diệm from running and led to an overwhelming majority of his supporters being elected.[v] Ultimately, however, beyond these titles, it was Mdm. Nhu’s connection to the Ngô-Đình family that enabled her to wield significant power over South Vietnam. Had she not come from a distinguished family, she would likely not have become Nhu’s wife, and had she not married Nhu, her life would likely have taken a much different turn.

Admittedly, Mdm. Nhu’s marriage was the determining factor for her rise to power, but the Ngô-Đình family that she married into at the time was not guaranteed to become the most powerful family in South Vietnam. When Ngô Đình Diệm returned to Saigon in 1954 as the new Premier of the State of Vietnam, Vietnam was in a state of great political upheaval. It was uncertain whether he would remain in power for long. The authority of the State of Vietnam was tenuous in various parts of the country and nonexistent in others. While North and Central Vietnam were primarily under the control of the Việt Minh (a Communist-led independence movement), in the South, much of the Mekong Delta was governed by warlords, and Saigon—the State of Vietnam’s capital—was controlled in some parts by the Bình Xuyên militia. More importantly, Diệm’s appointment as Premier had been an elaborate setup all along; one where he was bound to fail. With issues such as the influx of refugees from the North; private armies such as the Bình Xuyên Force, the Cao Đài religious sect’s militia, and the Hoà Hảo sect’s militia exerting substantial power in the South; and Southern supporters of the Việt Minh in hiding, the U.S. Army described the problems Diệm had to deal with as “insurmountable.”[vi] Awaiting his failure, the French had schemed to replace him with General Nguyễn Văn Hinh, who they could more easily influence. Yet, against all odds, Diệm emerged victorious in this power struggle (thanks in no small part to Ngô Đình Nhu and Trần Lệ Xuân).

While critics of the Ngô-Đình family often condemn them for practicing family rule, it is undeniable that both Ngô Đình Nhu and Trần Lệ Xuân played important roles in Diệm’s rise to power. From 1947 to 1954, Nhu built an extensive underground network with tens of thousands of supporters for Diệm through the Cần Lao Party, which helped sustain his presidency for the next nine years. As for Mdm. Nhu, she was a witty woman who knew how to make use of the political circumstances at the time. At a time when women were expected to be good housewives, Trần Lệ Xuân, following her husband, helped garner support for Diệm to solidify his position in the face of growing political threats from the French. Taking advantage of the mass migration of Catholics to South Vietnam at the time, she appealed to the aggrieved migrants who were harassed by the French-backed Bình Xuyên militia and organized a mass demonstration in favor of Diệm in 1954. The fruit of her labor was soon reaped when a few days later, General Hinh—who the French had conspired to replace Diệm with—was sent to France to never return. However, in return for securing Diệm’s hold on power, Mdm. Nhu was sent to exile in Hong Kong by the French’s request.[vii] As revealed in her memoir, she viewed her exile as a sign that people were starting to fear her: “They know for sure that from now on, I could not be pushed out of my position [Người ta biết rõ là từ nay, tôi sẽ không thể bị bẩy ra khỏi chiếc ghế của tôi].”[viii] Additionally, her family background also put her in danger. During the First Indochina War, because she belonged to the Ngô-Đình family, whose three other family members had been detained or executed by the Việt Minh,[ix][x] she was captured by the Việt Minh soldiers and faced several near-death instances while being held captive.[xi]

As Diệm consolidated his rule, Trần Lệ Xuân had great influence over him because he was grateful to her for cementing his hold on power. At dawn on November 11, 1960, three battalions of on-duty paratroopers who grew resentful of Diệm’s regime had seized control of key government centers in Saigon and threatened to attack the Presidential Palace. As Diệm was about to give in and negotiate with the rebels, Mdm. Nhu, who thought he was too softhearted, instructed him to launch a counterattack. In no time, they were able to retake the key city centers. Following the crisis, every time Diệm received congratulations, he would nod at Mdm. Nhu and acknowledge her: “It is thanks to madame [C’est grâce à madame].”[xii] As much as Mdm. Nhu enjoyed vast power from Diệm, so did her family. Diệm appointed her father to be the South Vietnamese ambassador to the U.S., her mother to be the South Vietnamese observer at the U.N., and her younger brother to be the palace spokesman.[xiii]

*

Nguyễn Thị Bình’s journey to become the public face of the PRG

On the other side of the conflict, Nguyễn Thị Bình came into the ranks of the Communist leadership based on her work as a cadre in a revolutionary organization. Although she belonged to a well-recognized family of patriots, she was not born into a powerful family. Her maternal grandfather Phan Châu Trinh was a Vietnamese nationalist famous for his drive to reform Vietnamese politics, society, and culture. Phan Châu Trinh was well-respected among Vietnamese patriots, but—having devoted his life to modernizing Vietnam—he did not amass wealth for himself and even spent much of his life in jail and exile due to his work. Moreover, Mdm. Bình spent part of her childhood in the rural areas of South Vietnam until her family moved to Cambodia when the French authorities assigned her father to work there as a geophysical surveyor. In her memoir, she noted that her father’s salary was “neither high nor low.”[xiv]

During the First Indochina War, Mdm. Bình worked many years as a cadre in the Communist-led Resistance. In 1945, when the Japanese overturned the French administration in Vietnam, her family returned home from Cambodia to help join the fight against the colonial powers.[xv] For the next three years, Mdm. Bình was committed to organizing for the Resistance and held different positions within it. Initially, she worked as secretary for a district’s Resistance Committee.[xvi] After moving to Saigon, she was appointed to the city’s Association of Women for National Salvation, a women-led organization dedicated to fighting for Vietnam’s independence.[xvii] In recognition of her dedication to the cause, she was admitted to the Communist Party in 1948.[xviii] She continued to lead demonstrations in Saigon until she was arrested by the French police in 1951 and was imprisoned in the Catinat Police Station, infamous for its inhumane treatment against its political prisoners.[xix] According to Mdm. Bình, in that prison, she underwent extreme torture for four years, yet she remained resolute about not giving in to the enemy.[xx] Her imprisonment granted her a badge of honor that distinguished her as a die-hard revolutionary and was viewed in a positive light by her fellow Party cadres. After the signing of the Geneva Accords, Mdm. Bình moved to the North and worked as Secretary to Nguyễn Thị Thập, President of the National Women’s Union. Her transition from working as a secret activist in Saigon to an apparatchik after moving to Hà Nội was a difficult one. Due to the different nature of her work, she struggled to adjust to working in a large state bureaucracy.[xxi] However, due to the ongoing war in the South, she returned to Saigon in 1961 to work for the National Liberation Front (NLF, or the “Việt Cộng”), South Vietnam’s resistance movement against the RVN.[xxii]

Leading up to the Paris Peace Conference, Mdm. Bình already had some diplomatic experience under the NLF. In an effort to expand the NLF’s diplomatic front, she joined various international meetings and official delegations. In 1961, she changed her name to Nguyễn Thị Bình since “Bình” means peace.[xxiii] At times, she also found herself in situations that were sensitive or tricky to handle. A funny instance was when President Sukarno of Indonesia invited her to dance at the gala despite her not knowing how to.[xxiv] Notably, in 1964, while attending a meeting in Moscow, she was put in a tough position of having to address Soviet Premier Khrushchev, “whose reputation has been challenged”[xxv] (Khrushchev was not viewed favorably by certain North Vietnamese leaders due to his Détente policy and criticism of Stalin[xxvi]). Thus, her career was put on the line. Fortunately, according to Mdm. Bình’s account, she handled the situation well.[xxvii]

In 1968, the U.S. and Hà Nội engaged in preliminary peace talks in Paris. Thanks to her “stellar record,” Mdm. Bình was recommended by Xuân Thuỷ, North Vietnam’s chief diplomat, to represent the NLF in the preparatory meetings for the upcoming Conference.[xxviii] The formal Conference, however, did not begin until January 25, 1969. Initially, Trần Bửu Kiếm, Chairman of the Front’s Foreign Affairs Commission, was made Head of the Delegation, while Mdm. Bình was only Deputy Head. According to another Minister in the PRG, Mdm. Bình was later elevated to the senior diplomatic post after Kiếm and Trần Hoài Nam, the other Deputy Head, got into a quarrel over Kiếm’s “unmonitored, self-initiated contacts in Parisian diplomatic circles and within France’s Vietnamese community,” leading both to be sent back home.[xxix] Soon after, she was appointed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the PRG (i.e., the public face of the “Việt Cộng”). Tellingly, she did not make the same mistake as her former superior.

While Mdm. Bình’s grandfather’s name—Phan Châu Trinh—indeed preceded her, she also worked alongside and built credibility among important people in the revolutionary organization, which aided her rise to prominence. Her relation to Phan Châu Trinh not only saved her at a critical moment in life but also formed her powerful connections. In 1951, when she was arrested by the French and was sentenced to either death or life imprisonment, activists in France, who were her grandfather’s acquaintances, intervened and reduced her punishment.[xxx] During her time working in the North, she was also invited to meet President Hồ Chí Minh, who highly regarded her grandfather.[xxxi] Nevertheless, the powerful connections that she forged herself while organizing for the Resistance should not be overlooked. In the Saigon’s Association of Women for National Salvation, she was closest to Duy Liên,[xxxii] who later became Vice President of the Hồ Chí Minh City People’s Committee. She was mentored by Bảy Huệ,[xxxiii] who later married Nguyễn Văn Linh, General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party from 1986–91 and the man behind the Đổi Mới policy, which profoundly changed Vietnam’s economy. She also met several high-ranking Communist leaders, including Lê Duẩn, Party General Secretary from 1960–86; Lê Đức Thọ, the most high-ranking Communist at the Paris peace talks and Lê Duẩn’s “right-hand man”[xxxiv]; and Phạm Hùng, Head of the Central Office for South Vietnam—North Vietnam’s headquarters in South Vietnam—and Vietnam’s future Prime Minister.[xxxv] More importantly, she worked as a Party grassroot organizer alongside Nguyễn Hữu Thọ,[xxxvi] who later became President of the PRG, whom she worked under. After moving to the North, she worked under Nguyễn Thị Thập, who was President of the National Women’s Union and a member of the Central Committee. In her memoir, Mdm. Bình likened her relationship with Mdm. Thập to that of a family member.[xxxvii]

*

Two different ways of rising to prominence

Looking back in time, the way Trần Lệ Xuân found herself at the center of power was reminiscent of some powerful queens in Vietnamese history. Like Mdm. Nhu, in the last one thousand years, several powerful women first gained their influence through their influence over their family. Ỷ Lan—Queen Regent famous for ruling Vietnam for dozens of years—first came into power as a concubine of King Lý Thánh Tông and the mother of King Lý Nhân Tông. Dương Vân Nga—Queen of two Kings—first gained power as the wife of King Đinh Bộ Lĩnh and effectively put a General, who she later married, on the throne after her husband’s passing. Lý Chiêu Hoàng—the last female monarch and the only Empress in Vietnam’s history—was the second daughter of King Lý Huệ Tông. Ironically, Mdm. Nhu’s rise to power was also reminiscent of Jiang Qing, who rose to power as Mao Zedong’s wife and spearheaded the Cultural Revolution in China.

In contrast, Nguyễn Thị Bình began her political career organizing for the Resistance during the First Indochina War. During the process, she built her own network within the Communist Party, which aided her rise to prominence. Historically, Vietnamese women leaders have played a significant role in national consciousness, with famous figures like the Trưng Sisters or Lady Triệu. However, ever since Lady Triệu’s uprising against the Eastern Wu dynasty in 248 CE, every woman who rose to national leadership in Vietnam has been a wife, mother, or daughter of some men in power. It was not until the era of the Communist revolution—after nearly 1700 years—that women began to lead in their own rights again.

Through their rise to power, Mdm. Nhu and Mdm. Bình transcended the North-South dichotomy. Mdm. Nhu, whose mother’s family hailed from royal lineage in the city of Huế in Central Vietnam, was born in Hà Nội and later served the South Vietnam regime. Conversely, Mdm. Bình considered Quảng Nam province of Central Vietnam to be her “native province” and “ancestral home,”[xxxviii] but she was born in Sa Đéc province of South Vietnam and later served in the Communist regime, which ruled North Vietnam after the geneva Accords.

*

How Tran Le Xuan and Nguyen Thi Binh interacted with their organizations

During the Vietnam War, both Mdm. Nhu and Mdm. Bình emerged as the face of their organizations, drawing worldwide media attention. Though most credited for their role as diplomats, they were also politicians. Initially, with the backing of the Ngô-Đình family, Mdm. Nhu, despite not holding high office, could impose her agenda on the RVN. After a tipping point, however, her assertiveness contributed to her demise. In the opposing camp, to stay in office, Mdm. Bình had to strictly follow Party orders, and even a slight deviation could put her career at risk.

Trần Lệ Xuân as de facto First Lady

Officially, Mdm. Nhu was President Diệm’s hostess and a member of the RVN National Assembly, but her influence extended far beyond that due to her strong hold over Diệm, which was a double-edged sword. In the early years, it allowed her to push her agenda and grab power despite opposition from elements within South Vietnam, but once tensions reached a breaking point, these elements came together to try and silence her.

Mdm. Nhu asserting herself

The Family Code law is a prime example of Mdm. Nhu pushing her agenda with Diệm’s support. Outlawing polygamy, concubinage, and even divorce while giving women the right to manage their own finances after marriage, the law was intended for a “woman [to] become a man’s equal.”[xxxix] Mdm. Nhu explained, “Before the family code of which I am the author, women were legally classified with minors and the insane. They wasted all their intelligence and energy in fighting each other, and to get what? A man, a protector. And once they got him, they had to fight each other to keep him.”[xl] However, when the law was first proposed to the National Assembly, it was met with great objection from the male senators who claimed that these new rights were much too soon for women and was not passed until she leaned on her connection to Diệm to forcibly pass it. When faced with criticism, she was rumored to have called the leader of the Assembly a “pig.”[xli] In effect, the law enjoyed the support of the South Vietnamese populace though some questioned her intentions. According to Monique Brison Demery, author of Mdm. Nhu’s biography “Finding the Dragon Lady,” “it seemed that the majority of the Vietnamese people welcomed legislation reforming the status of women in the Family Code.”[xlii] On a trip to the countryside, Mdm. Nhu was greeted warmly by the women there, who reportedly thanked her for the law. However, some South Vietnamese thought that they may not have been sincere in thanking her.[xliii] Some even speculated that she had ulterior motives in passing it and that the ban on divorce was intended to prevent her older sister Lệ Chi from divorcing her husband.[xliv] When the Ngô-Đình family lost power in 1963, the law was also rescinded, to which historian Balazs Szalontai argues, “Had the law been backed up by the activities of a substantial number of self-mobilized women, it might have had a better chance to survive Diệm’s downfall.”[xlv]

In 1961, Mdm. Nhu passed the Morality laws, an extension of her Family Code, to ban dancing, beauty contests, gambling, fortune-telling, cockfighting, prostitution, contraception, and under-wire bras. In her book, Demery states that these laws “didn’t accomplish much besides angering the people.”[xlvi] Historian Hue-Tam Ho Tai, who lived in Saigon when these laws were passed, further notes, “The laws that were passed to uphold morality were widely derided. One example was the banning of longline bras, which she quite obviously made use of herself. Also, people could not quite believe that this was as urgent a matter as the war that was going on.”[xlvii]

In 1962, Mdm. Nhu commissioned a statue of the Trưng Sisters, Vietnam’s first national women heroes, to be built in Saigon. The statue ironically bore a striking resemblance to her own facial features,[xlviii] attracting much ire; it was thus not only pulled down on the day a group of generals staged a coup against the Ngô-Đình family[xlix] but was also trampled on by a group of South Vietnamese.[l] It also received criticism for its cost, a large sum at the time for a developing country at war.[li]

While much of Mdm. Nhu’s power was trickled down from her family, she also attempted to attain power herself. In 1961, she established the Women Solidarity Movement, the women’s wing of the Cần Lao Party founded by her husband. The organization not only helped build her a network of 1.2 million women supporters[lii] but also served as a platform for her to assert herself. Despite its large membership, the movement appealed mainly to the women of the elite, who joined to curry favor from her, and not to the majority of South Vietnamese women.[liii] Additionally, she even organized her own Women’s Paramilitary Corps[liv] and—according to RVN Secretary of State Nguyễn Đình Thuần—her own secret police squad headed by her younger brother Khiêm.[lv]

Besides pushing her agenda and grabbing power, Mdm. Nhu also offended not so few people with her words. Her public statements played a part in shaping the U.S. and the RVN’s negative perception of her. In her articles published in the Times of Vietnam, she accused American intelligence officers in Saigon of being “Nazi-like cynical young men” who conspired against the government and called President Kennedy “intoxicated.”[lvi] Then, in one speech, she referred to the Kennedy administration as “false brothers” to the South Vietnam’s government.[lvii] Over the years, her media appearances earned her much bad rep that President Kennedy insisted on her “shutting up.”[lviii] Likewise, RVN Secretary of State Thuần “personally deplored” a speech Mdm. Nhu gave to the Women’s Solidarity Movement, and at one point, even Diệm acknowledged that one of her own speeches was “politically stupid.”[lix]

Over time, Mdm. Nhu’s outspokenness made her many enemies within the RVN, setting the stage for her eventual downfall. According to a 1963 C.I.A. report, “the educated and articulate elements of the population, including the military,” expressed an “intense” and “very personal hostility” towards Mdm. Nhu “on the grounds that she is vicious, meddlesome, neurotic, or worse.” The report also revealed that Mdm. Nhu and Ngô Đình Cẩn, Diệm’s younger brother who ruled the Central region of South Vietnam, detested each other.[lx] Similarly, Bửu Hội, a South Vietnam’s top diplomat serving as ambassador to multiple countries, said, “Madame Nhu must clearly be eliminated.”[lxi] In his memoir, General Đỗ Mậu, who was part of the 1963 coup, also accused her of forcing the Family Code down the public’s throat and of overstepping her power by claiming the right to speak at the International Parliamentarians Conference in Rome and Rio de Janeiro despite not being Head of the Delegation.[lxii]

Nevertheless, Madame Nhu did receive support from some elements within South Vietnam. In 1956, she was elected to the RVN National Assembly partly thanks to the support of a group of Catholic refugees from North Vietnam, who were part of the mass demonstration she organized in favor of Diệm in 1954.[lxiii] One of Mdm. Nhu’s most loyal supporters was the Times of Vietnam (a newspaper based in Saigon), which acted as her mouthpiece by publishing her speeches and articles that criticized the U.S. government,[lxiv] many of which Mdm. Nhu claimed to have written herself.[lxv] However, all this support did not lead to her staying in power. During the 1963 coup, the office of the Times of Vietnam was also “sacked.”[lxvi]

*

The turning point: Buddhist Crisis

The turning point in Mdm. Nhu’s career was arguably her remarks during the Buddhist crisis. In 1963, as tensions erupted between South Vietnam’s Buddhists and the Ngô-Đình family (who were Catholics and included a brother who reached the rank of Archbishop), discontent against the Diệm regime mounted. On June 11, 1963, Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức set himself on fire in protest, and his burning image made headlines around the world. Despite the publicity of this incident, Mdm. Nhu proceeded to publicly mock the monk, saying that he had been “barbecued” with “imported gasoline.”[lxvii] Her comments caused uproar, turning the Buddhists (who constituted nearly eighty percent of South Vietnam’s population[lxviii]) and elements of the RVN and U.S. governments against her. Even her own parents, who were the South Vietnamese Ambassador to the U.S. and observer at the U.N., resigned from their jobs and disowned her. Calling her a “monster,” her mother told the Vietnamese community in New York and Washington to “run her over with a car” and to throw eggs and tomatoes at her whenever she appeared in public.[lxix] Mdm. Nhu later confessed in an interview with a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, “I used those words because they have shock value. It is necessary to somehow shock the world out of this trance in which it looks at Vietnam.”[lxx] Unfortunately, her boldness this time had only brought the RVN to its brink sooner as the U.S. threatened to disassociate themselves from the Diệm regime. In a telegraph to the U.S. Embassy, the U.S. Department of State described her comments as “inflammatory” and “most unwise.”[lxxi] In a later telegraph, U.S. Ambassador Nolting reported that “Madame Nhu is out of control of everybody.” He also warned Diệm that “he could not expect to maintain present relationship with [the] U.S. government if he would not take this matter into his own hands.”[lxxii]

Even when tensions were high, Mdm. Nhu continued to assert herself. In the midst of the Buddhist crisis, with pressure from the U.S., Diệm negotiated with the Buddhist leaders and made several concessions to soften the situation. Yet, the day after the compromise, Mdm. Nhu issued a resolution through the Women Solidarity Movement to the press, charging that the Buddhists were anti-nationalists “exploited and controlled by communism.”[lxxiii]

*

Mdm. Nhu’s pushback

Near the end of her career, as the Buddhist crisis played out, there were discussions among several high-ranking RVN leaders, including Vice President Thơ, Secretary of State Thuần, Ambassador Bửu Hội, and even Ngô Đình Nhu, of pushing back Mdm. Nhu, but these plans did not completely follow through. In a telegram to the U.S. Department of State on August 10, these officials were reportedly thinking of giving her a “leave of absence” in Rome.[lxxiv] In another telegram on August 24, Diệm was said to have written her a letter, ordering her “to make no public statements and give no press conferences.” He also instructed those in the RVN Information Department “not to print any statement she might make.”[lxxv] Then, on September 2, the C.I.A. in Saigon reported that as the “first step to save face,” Nhu volunteered for his wife to take a trip to the U.S.[lxxvi] Disguised as a foreign tour, Mdm. Nhu promptly departed Vietnam a week later, which, according to U.S. Ambassador Nolting, was intended to “keep her out of the country for three to four months.”[lxxvii] However, an important condition of the plan that “she should be kept from making speeches”[lxxviii] was ignored as she continued to denounce the U.S. on their own soil, saying that they were soft on communism and that she was a victim.[lxxix]

Mdm. Nhu’s outspokenness was also not well-received by the U.S. government, contributing to the straining relationship between the U.S. and Diệm. Important Kennedy officials, such as Secretary of State Dean Rusk and U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, felt threatened by her influence over Diệm and wanted to remove her from power.[lxxx] In a conversation between President Kennedy and his close confidant Paul B. Fay, Under Secretary of the Navy, Kennedy blamed Mdm. Nhu for Diệm’s death and even supposedly compared her to a female dog.[lxxxi] His wife, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, was also open about her disdain towards Mdm. Nhu, saying in a 1964 interview that she “was everything Jack [John F. Kennedy] found unattractive” and suspected her of being a lesbian.[lxxxii] Similar hostility was expressed by the Senator of Ohio Stephan Young at the 88th Congress, who asserted that she was “too big for her britches.”[lxxxiii] Despite the U.S.’ insistence to use stronger measures against Mdm. Nhu, Diệm would refuse to listen. In a telegraph to the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Embassy expressed frustration over the fact that the most Diệm was willing to do was to tell Mdm. Nhu to take a rest, commenting that “results to date have been worse than negative.”[lxxxiv] The situation did not take a turn for the better as the Diệm regime was ultimately toppled in 1963. The Pentagon Papers, published in 1971, detailed the U.S.’ involvement in the coup:

“Beginning in August of 1963 we variously authorized, sanctioned and encouraged the coup efforts of the Vietnamese generals and offered full support for a successor government. In October we cut off aid to Diem in a direct rebuff, giving a green light to the generals. We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans and proposed new government.”[lxxxv]

While it is fair to question if things would have turned out differently had other RVN and U.S. leaders intervened sooner, Mdm. Nhu was not someone who could be easily dealt with. Since she was Diệm’s sister-in-law, many did not dare to oppose her directly. As RVN Secretary of State Thuần explained, “It was a family matter in which it was awkward to intrude.”[lxxxvi] Moreover, although some have tried to intervene in the past, Diệm would simply brush their suggestions aside. In a conversation with some members of the U.S. government, Ambassador Bửu Hội expressed his frustration over this issue: “President Diệm was still not convinced that she is not harmful,” and “the President needs to be told just how harmful she is.”[lxxxvii]

In 1963, Ngô Đình Diệm and Ngô Đình Nhu were murdered in a coup led by a group of dissenting South Vietnamese generals, marking Mdm. Nhu’s fall from grace. No longer in power, she moved with her children to Europe, living the rest of her life away from public view. However, even after being stripped from power, she would continue to throw attacks at the U.S. government, blaming them for the fall of South Vietnam and telling reporters that her husband and brother-in-law’s deaths were “murders either with the official or unofficial blessing of the American government.”[lxxxviii] In her later years, she had to resort to making money through interviews and photographs, charging $1,000 for a photograph and $1,500 for an interview plus photograph.[lxxxix]

*

Explaining Mdm. Nhu

Mdm. Nhu’s behaviors bewildered not so few people, including herself, to which she eventually acknowledged, “Perhaps I should have been a little more humble about our family’s greatness.”[xc] Admittedly, there is no clear-cut answer to her actions. However, to understand her, certain details may not be overlooked. Despite being born with a silver spoon, Mdm. Nhu occupied the lowest status in her household as the middle daughter and thus had to honor and obey her elders, parents, and even siblings. Resentful of the low status she had in her family, she would often rebel. “It is something like a game my [brother] used to tease me with when I was a child. I would be sitting down, and he would say, ‘Sit down.’ So to show that I was not sitting because he ordered me to do it, I would stand up,” she shared. [xci] Even at a young age, she believed she was entitled to more and endeavored to gain the attention of those around her, such as by crying louder and trying hard in school.[xcii] Despite her best efforts, she never earned her parents’ approval. To escape her family’s mistreatment, she married Ngô Đình Nhu, whose family was of similar status to hers. Unlike other girls her age, her defiance was further exemplified through her rejection of arranged marriages as she later chose to marry Nhu herself.[xciii] Her marriage not only “completely changed her status in the family [cương vị trong gia đình tôi hoàn toàn thay đổi]”[xciv] but was also key to her rise to power. As her influence grew, with a rebellious nature, she was empowered to behave more recklessly. The Ngô-Đình family's power in South Vietnam was largely unchecked during the late 1950s and early 1960s, and Mdm. Nhu had such a strong hold over Diệm that many thought it would be “practically impossible” to remove her. RVN General Trần Văn Đôn explained to American advisors that “Madame Nhu can be extremely charming” that she could charm Diệm into saying “yes when he wants to say no.” Diệm also thought of her as “his platonic wife” as she “relieves his tension, argues with him, needles him, and, like a Vietnamese wife, is dominant in the household.”[xcv] Hence, with strong support from the Ngô-Đình family, Mdm. Nhu could push through things that offended some people.

*

Nguyễn Thị Bình’s career in the Communist regime

In the early 1960s, Nguyễn Thị Bình began her diplomatic career, just as when Mdm. Nhu stepped away from the world stage. While Mdm. Nhu’s time in power was short-lived, Mdm. Bình would continue to serve under the Communist Party and hold different offices until she reached seventy-five years of age. For most of her career, Mdm. Bình was tasked with the role of “people-to-people diplomacy,” which involved maintaining good relations with the people of other countries. While she was not tasked with “leader-to-leader diplomacy,” she also maintained good relations with the leaders of some countries.

Mdm. Bình as Foreign Minister of the PRG

At the Paris Peace Conference, despite her official title as Foreign Minister and Head Delegate of the PRG, Nguyễn Thị Bình admitted herself that “the main leaders in our negotiations [những nhà lãnh đạo chủ chốt của đàm phán của ta]” were Lê Đức Thọ and Xuân Thuỷ.[xcvi] Although she was ultimately one of four signers of the Paris Peace Accords, actual negotiations between the U.S. and the DRV happened mainly behind closed doors, while public negotiations between the four parties with the presence of the RVN and the PRG were much less important.[xcvii] Therefore, Mdm. Bình assumed more of a role as a public figure to affirm the PRG’s purpose and significance and was exposed to much media attention. Despite her strong stance against the U.S., Western media often reported favorably of her. According to the New York Times, Mdm. Bình made her mark at the Paris peace negotiation as her delegation’s “most visible and well-publicized” representative.[xcviii] French news agency Agence France-Presse also portrayed her in a favorable light: “Mdm. Bình wore a traditional áo dài made from green silk fabric, looking very comfortable. Sometimes, Mdm. Bình smiled, making her face even brighter, answering reporters clearly and precisely, making people feel like they were standing in front of a brave, confident lady.”[xcix]

However, this was not always the case. At times, reporters would intentionally ask questions that put Mdm. Bình is in a difficult position. According to her account, some reporters would ask in a critical tone whether she was a member of the Communist Party, while others commented, “Your name means ‘peace,’ but you speak only of war.”[c] Even worse, certain newspapers would either unintentionally or even intentionally twist her words in their reporting.[ci] In her memoir, Mdm. Bình would often express her worry and fear of being a diplomat during wartime as everything she said could be used against her own country.[cii]

Within the Communist Party, Nguyễn Thị Bình was regarded as a good public face to represent their struggle. In his diary entry on November 4, 1968, Xuân Thuỷ wrote about his impression of Mdm. Bình when she first arrived in Paris: “Mdm. Bình was like a Queen, welcomed like a Head of State, with all the formalities. Mdm. Bình shocked public opinion in Paris and the world. The NLF flag flew in Paris. Wonderful! It is rare! [Bà Bình như bà hoàng, được đón như quốc trưởng, đủ nghi thức chính quy. Bà Bình đã làm chấn động dư luận Paris và thế giới. Cờ Mặt trận đã tung bay ở Paris. Rất tuyệt! Thật hiếm có!]”[ciii] During his talk with Mao Zedong, Phạm Văn Đồng, Prime Minister of the DRV, also boasted Mdm. Bình as a comrade who was “good at diplomatic struggle.”[civ] According to Vietnam expert Lady Borton, President Hồ may have nominated Mdm. Bình for her role in “people-to-people diplomacy,” commenting that “President Hồ knew that Nguyễn Thị Bình possessed the generous, open, and honest personality needed to win over those holding different views.”[cv] Her comment may have some merit given that Hồ Chí Minh met Mdm. Bình at least twice, one of which was just two months before her appointment as PRG’s Foreign Minister.[cvi]

A central part of her job was to maintain friendly relations with people from other countries, to which she did well. Nguyên Ngọc—former pro-Communist author and now dissident—even said, “Mdm. Bình is the Vietnamese person with the most friends across the world.”[cvii] In France, women in the Union of French Women joked that French people knew more about Mdm. Bình than their own President.[cviii] In the U.K., many gathered to hear her speak at Trafalgar Square. Some Americans in the anti-war movement also wore T-shirts with her portrait printed on them,[cix] and some women even named their children “Bình.”[cx] “The impression one gets of her is of quietness and neatness—someone terrifically self-contained and self-possessed,” said a Westerner at the time. “When you see her, you know there is someone pretty important.”[cxi] Likewise, in her book “The Heart of the World,” Swedish writer Sara Lidman underscored Mdm. Bình’s impact, “Wherever there is Mdm. Bình, people no longer want to see anyone else. Whenever Mdm. Bình speaks, people no longer want to hear anyone else.”[cxii]

On the other hand, her 1970 visit to India sparked a huge controversy. While she was greeted cordially by the Communist organizations there, she was met with great opposition from a number of right-wing parties with demonstrators waving black flags and shouting “Mao’s agent go back!” to her at the airport. Likewise, some rightest members of Parliament charged that she was a “tool of Chinese Communism.”[cxiii]

As a diplomat, Mdm. Bình met several world leaders, gaining respect from some and favor from others. She heaped praises from many important people in power, including Zhou Enlai, who described her as “very sharp.”[cxiv] In another instance, a Soviet official, who accompanied her to meet the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR and members of the Supreme Soviet, recalled, “Everyone was impressed with her mind, dexterity, intelligence, and her understanding of the work she does.”[cxv] Mdm. Bình also received help from various world leaders. In Sweden, Prime Minister Olof Palme invited her to take part in the Swedish Social Democratic Party Congress as the only foreign representative to speak about the Vietnam War. She also joined the Prime Minister to lead demonstrations in support of the Vietnamese people’s struggle.[cxvi] In Algeria, President Houari Boumedienne and Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who later also became President, considered her a “close friend” and reserved a villa in the capital city under her name.[cxvii] President Boumedienne even said to Mdm. Bình, “I invite you to travel free of charge whenever you are on a mission to a country covered by our airline.”[cxviii] On her trip to Iraq in 1975, seeking “to borrow oil,” Saddam Hussein (at the time, Vice President of Iraq) offered to “give Vietnam four hundred thousand tons of oil and lend 1.5 million tons with a preferred interest rate.” In 2002, when she returned to negotiate debt repayments, Saddam Hussein said, “You Vietnamese needn’t worry. I know you face difficulties. We will view this debt as paid.”[cxix]

Despite being dubbed the “Việt Cộng Queen,” Mdm. Bình did not achieve everything she wanted as a diplomat. For example, she failed to get Soviet leaders to use terms such as “American imperialism” or “aggression” to describe the U.S.’ involvement in Vietnam.[cxx] In another example, in an attempt to get the U.S. to withdraw troops from Vietnam, Mdm. Bình wrote a letter to appeal to the U.S. Congress. However, her letter was rejected on the grounds that it was “not constructive” and that it interfered with the U.S.’ internal affairs.[cxxi]

One story suggests that Mdm. Bình was far from a prescient and experienced stateswoman. In 1971, while in Sweden, she was asked by an elderly woman, “Have you Vietnamese friends thought about what you will do after you’ve chased out the Americans and then the Chinese arrive?” In response, she explained that “no such incident could transpire between socialist countries” for they “shared the comradely feeling of brothers and sisters.” In hindsight, Mdm. Bình was “naïve,” which she also admitted herself.[cxxii] Just eight years later, China launched a surprise invasion of Northern Vietnam, assaulting six provinces and resulting in tens of thousands of casualties.[cxxiii] Other events, such as China’s support for the Khmer Rouge (which launched a series of attacks on Vietnamese border provinces) and the Chinese invasion of the Spratly Islands in 1974 and attack on John South Reef in 1988, further exposed Mdm. Bình’s shortcoming.

*

Mdm. Bình’s career after the Vietnam War

Shortly after Vietnam’s reunification in 1976, Mdm. Bình became Education Minister of the now Socialist Republic of Vietnam. During her term as Education Minister, she was able to solve major problems in Vietnam’s education system and gain the support of those working under her. When she first assumed this role, the education system in Vietnam was in a dire state. Not only were there discrepancies between the education systems in the North and in the South, a striking ninety-five percent of Southerners were also illiterate.[cxxiv] To bridge the education gap between the two regions, she organized a major mobilization for Northern teachers to come to the South. By 1983, the Ministry of Education had successfully set up a network of public schools in every Southern province, district, and commune.[cxxv] Her Light-of-Culture campaign also helped eradicate illiteracy among ninety-four percent of participants in the program.[cxxvi] One of Mdm. Bình’s greatest achievements, however, was her advocacy for higher teacher salaries. The years 1979 and 1980 were difficult for the Vietnamese population due to the ongoing conflicts with China and the Khmer Rouge and witnessed a large labor shortage in the education sector. To address this problem, she and her colleagues came up with a proposal, which successfully persuaded the State to readjust educational salaries. In addition to her strides to improve Vietnam’s education system, Mdm. Bình also had the support of her subordinates as she met “no resistance or conflict worth noting within the ministry.” In fact, she received much help from her colleagues during her first days, which helped her adjust to her new role as an administrator.[cxxvii]

After ten years in the Ministry of Education, Mdm. Bình transitioned back to “people-to-people diplomacy”—her “forte”[cxxviii]—serving as the chair of the National Assembly’s Foreign Relations Committee. It was also around this time in 1986 that she no longer participated in the Central Committee, moving away from the center of power. While it is difficult to pinpoint the exact answer for her demotion, a review of her time as Education Minister suggests a few explanations. A contentious issue that arose during this time was the lack of funding from the State. With very limited resources, she had to carry out the Politburo's Decision fourteen on Education, which demanded wide-ranging education reforms, including increased early childhood and vocational education and universal education.[cxxix] In 1985, funding for education reforms was cut; when she asked Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng about it, he told her, “If you can do it without money, you are truly smart.”[cxxx] In the same year, she faced criticism from some Party members who deemed these education reforms a failure. As Mdm. Bình admitted herself, she has “not properly achieved [the] major point” of Decision fourteen as some aspects of the education system remained “dogmatic” and “willful.”[cxxxi] The problems she faced may have pushed her back to diplomacy. Furthermore, near the end of her term as Education Minister, Mdm. Bình got into trouble with the “economic police” due to her protecting the Educational Services Company, a company founded in 1984 by the Ministry of Education and was partially funded by staff members at the Ministry. At a time when many were struggling to make ends meet, this company provided additional income through making products such as pottery, educational materials, and kindergarten toys. However, it also led them to be investigated and “dealt with [xử lý]”[cxxxii] by the police when there was “money lost in a trade.”[cxxxiii] This story highlights Mdm. Bình’s difficulties in dealing with the inherent contradictions in Vietnam’s command economy at the time. Under this command economy, private enterprises were mostly prohibited, state-owned enterprises were severely constrained by government decrees, people were “desperately poor,” and “anyone making even the smallest profit from a creative enterprise suffered from police watchers and became the topic of malicious gossip.”[cxxxiv] This episode in her career may have contributed to her pushback as Mdm. Bình wrote in her memoir, “My resolute attitude on this matter brought me countless problems.”[cxxxv]

In 1992, at the age of sixty-five, Mdm. Bình was nominated to become the country’s Vice President. She, however, expressed her discontent upon receiving this news. In thanking Prime Minister Đỗ Mười, she said, “It’s regrettable that when I was still young and could have made a substantial contribution, you comrades didn’t evaluate me accurately.”[cxxxvi] While it is unclear what she meant by “when I was still young,” she may have been referring to the year 1986 since it was when she no longer served on the Central Committee and moved away from the center of power. One story might explain her return to the spotlight as Vice President (even though she would never be part of the Central Committee again): Her colleagues compared her to Kim Ngọc,[cxxxvii] Communist Party Secretary of Vĩnh Phúc province, who pioneered relaxing the command economy and opening up private enterprise through a scheme similar to the Chinese “household responsibility system.” Kim Ngọc had to write a disciplinary report and admit that his idea was a “serious mistake.”[cxxxviii]It was not until ten years after the 1986 Đổi Mới policy (which marked Vietnam’s transition from a command economy to a market economy) that his efforts were finally recognized, and he was awarded the Order of Independence.[cxxxix] Around the same time, Mdm. Bình was asked to become Vice President by other Communist leaders.

*

Comparing Mdm. Nhu and Mdm. Bình in their roles

As public figures representing their political regimes, Mdm. Nhu and Mdm. Bình are most recognized today for their media presence. Acclaimed as the “Việt Cộng Queen,” Mdm. Bình was often portrayed favorably by the media, garnering praise for her diplomatic skills, whereas Mdm. Nhu received much criticism for her bold remarks. Their different media treatments could be partially attributed to whether they conformed to the prevailing gender norms at the time. For Mdm. Bình, being a woman diplomat, especially coming from a “weaker nation,” acted as a leverage during negotiations, helping attract attention and win over people’s sympathy.[cxl] According to Mdm. Bình, “If you are a woman who knows how to behave tactfully, people will view you more favorably and be more willing to listen to what you have to say [Nếu mình là phụ nữ biết ứng xử khôn khéo thì người ta cũng dễ có tình cảm hơn, sẽ nghe những điều mình muốn nói về lập trường của mình].”[cxli] On the other hand, Mdm. Nhu did not act according to these expectations and attracted much negative attention for herself. Over the years, due to her influence over Diệm and sharp tongue, she curated for herself the image of a power-hungry and domineering woman in the public eye, which was deemed unfavorable back then.

Mdm. Nhu’s and Mdm. Bình’s public image, however, did not accurately reflect their actual power levels within their organizations, nor did their official titles. Behind her much glorified media persona, Mdm. Bình never made it to the Politburo and was only in the Central Committee for five years. Throughout her career, Mdm. Bình held many grand titles, including Foreign Minister of the PRG and Education Minister of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. In these roles, despite being a cabinet member, she was still subjected to the orders of higher-level Party officials and could not act completely independent. The highest office she held was Vice President—a largely ceremonial role. In contrast, while many only know of Mdm. Nhu for her outspokenness via the media, she actually wielded significant power over South Vietnam despite occupying insignificant positions as President Diệm’s hostess and National Assembly member. Not only did she orchestrate important government moves such as the Family Code law and the Morality laws, she also gained considerable power herself, to the point of building her own support system, paramilitary, and even secret police.

Due to their power levels, Mdm. Nhu and Mdm. Bình also exercised different degrees of agency. On the one hand, Mdm. Nhu, with Diệm’s support, could impose her will on others in the RVN. Notably, her Family Code law and Morality laws, despite their unpopularity, were still passed by the RVN National Assembly. In some respects, she may have gotten too much power for her own sake, which resulted in her overthrow in the 1963 coup. On the other hand, Mdm. Bình had some agency but could only exercise it within the constraints of her Party. As Education Minister, she protected the people running the Educational Services Company in her Ministry. However, soon after this act, she faced a minor pushback and was no longer in the Central Committee by 1986. Another example of her agency was her interventions in some legal cases as Vice President. One case involved a famous overseas Vietnamese who was imprisoned by local authorities. Disagreeing with the authorities’ decision to imprison him, Mdm. Bình first privately discussed the case with Party leaders and then publicly spoke about it in the national legislature, which made people raise questions regarding her intervention.[cxlii] Then, in 2002, she was sought out by an old friend to help a farmer to have his son’s case reexamined by the court. She explained the situation to the Party General Secretary, and thanks to her intervention, the farmer’s son’s execution was prevented.[cxliii]

[i] Monique Brinson Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady: The Mystery of Vietnam’s Madame Nhu (New York: PublicAffairs, 2013), 44, Kindle.

[ii] Nguyễn Thị Bình, Family, Friends, and Country: Memoir, trans. Lady Borton (Hà Nội: Tri Thức Publishing House, 2015), 36, https://www.scribd.com/document/722697627/Family-Friends-and-Country-Nguyen-Thi-Binh. Accessed December 9, 2024.

[iii] Phạm Hoàng Điệp, “Một Dân Tộc Dốt Là Một Dân Tộc Yếu (An Ignorant Nation Is a Weak Nation),” Cổng thông tin điện tử Cà Mau, December 2, 2016, https://shorturl.at/hN3fP. Accessed January 23, 2025.

[iv] “South Viet Nam: The Queen Bee,” Time Magazine, August 9, 1963, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,870390-4,00.html. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[v] Edward Garvey Miller, Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the fate of South Vietnam (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 145, Kindle.

[vi] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 88.

[vii] Ibid., 95-96.

[viii] Ngô-Đình Quỳnh, Ngô-Đình Lệ Quyên, and Jacqueline Willemetz, Viên Sỏi Trắng: Hồi Ký của Bà Ngô-Đình Nhu (The White Stone: The Memoir of Madame Ngô-Đình Nhu) (Oregon: U.S.-Vietnam Research Center – University of Oregon, 2023), 71.

[ix] Miller, Misalliance, 32.

[x] Nguyễn Hữu Hanh, Hồi Ký Nguyễn Hữu Hanh (Nguyễn Hữu Hanh’s Memoir) (Viet-Studies, 2008), chap. 1, https://www.viet-studies.net/kinhte/HoiKy_NguyenHuuHanh.htm#1. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[xi] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 66-67.

[xii] Ibid., 118-121.

[xiii] Ibid., 96.

[xiv] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 33-34.

[xv] Ibid., 40.

[xvi] Ibid., 56.

[xvii] Ibid., 60.

[xviii] Ibid., 62.

[xix] Ibid., 73.

[xx] Nguyễn Thị Bình, “Interview with Madame Nguyễn Thị Bình, Acting Chief of the National Liberation Front Delegation at the Vietnamese Peace Conference,” Socialist Woman 1 (January 27, 1969): 3-5, https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/document/britain/socialist-women/socialist-woman-v1-no1-mid-february-1969.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[xxi] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 95.

[xxii] Ibid., 99.

[xxiii] Ibid., 100.

[xxiv] Ibid., 103.

[xxv] Ibid., 112.

[xxvi] Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Hanoi’s War: An international history of the war for peace in Vietnam (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 41, Kindle.

[xxvii] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 112.

[xxviii] Nguyen, Hanoi’s War, 231.

[xxix] Trương Như Tạng, David Chanoff, and Đoàn Văn Toại, A Vietcong Memoir: An Inside Account of the Vietnam War and Its Aftermath (New York: Vintage Books, 1985), 237.

[xxx] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 80.

[xxxi] Ibid., 96.

[xxxii] Ibid., 60.

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Nguyen, Hanoi’s War, 21.

[xxxv] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 72.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 356.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 96.

[xxxviii] Ibid., 26.

[xxxix] Trần Lệ Xuân, “Code of the Family,” MSU Vietnam Group Archive, October 7, 1957, https://vietnamproject.archives.msu.edu/recordFiles/159-547-3089/UA17-95_000490.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[xl] Kathie Amatniee, “Madame Nhu at East House,” The Harvard Crimson, October 18, 1963, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1963/10/18/madame-nhu-at-east-house-pmy/. Accessed December 30, 2024.

[xli] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 110.

[xlii] Ibid., 102.

[xliii] Ibid., 133.

[xliv] Chung Nguyen, “Women’s Rights/Madame Nhu,” Vietnam Studies Group, February 28, 2011, https://sites.google.com/uw.edu/vietnamstudiesgroup/discussion-networking/vsg-discussion-list-archives/vsg-discussion-2011/womans-rightsmadam-nhu. Accessed December 20, 2024.

[xlv] Balazs Szalontai, “Women’s Rights/Madame Nhu,” Vietnam Studies Group, February 28, 2011, https://sites.google.com/uw.edu/vietnamstudiesgroup/discussion-networking/vsg-discussion-list-archives/vsg-discussion-2011/womans-rightsmadam-nhu. Accessed December 20, 2024.

[xlvi] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 127.

[xlvii] Hue-Tam Ho Tai, “Women’s Rights/Madame Nhu,” Vietnam Studies Group, February 27, 2011, https://sites.google.com/uw.edu/vietnamstudiesgroup/discussion-networking/vsg-discussion-list-archives/vsg-discussion-2011/womans-rightsmadam-nhu. Accessed December 20, 2024.

[xlviii] A. J. Langguth, Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 186, Kindle.

[xlix] “Central Intelligence Agency’s Memorandum of the Situation in South Vietnam,” National Security Archive, November 2, 1963, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB101/vn24.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2024.

[l] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 148.

[li] Langguth, Our Vietnam, 186.

[lii] T. Rees Shapiro, “Mme. Ngo Dinh Nhu, Who Exerted Political Power in Vietnam, Dies at 87,” The Washington Post, April 26, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/mme-ngo-dinh-nhu-who-exerted-political-power-in-vietnam-dies-at-87/2011/04/26/AFpwwF2E_story.html. Accessed December 9, 2024.

[liii] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 132-133.

[liv] Shapiro, “Mme. Ngo Dinh Nhu.”

[lv] “Memorandum From the Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (Hughes) to the Secretary of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, September 6, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d68. Accessed January 6, 2025.

[lvi] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 156.

[lvii] Colby Itkowitz, “‘The Dragon Lady’: How Madame Nhu Helped Escalate the Vietnam War,” The Washington Post, September 26, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/09/26/the-dragon-lady-how-madame-nhu-helped-escalate-the-vietnam-war/. Accessed December 9, 2024.

[lviii] “Editorial Note,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, September 6, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d67. Accessed January 10, 2025.

[lix] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume II, Vietnam, 1962, Office of the Historian, March 20, 1962, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v02/d118. Accessed January 6, 2025.

[lx] “Memorandum From the Deputy Director for Plans, Central Intelligence Agency (Helms), to the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs (Hilsman),” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 16, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d256. Accessed January 6, 2025.

[lxi] “Memorandum of Conversation,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, October 2, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d168. Accessed January 10, 2025.

[lxii] Đỗ Mậu, “Ngô Đình Nhu và Trần Lệ Xuân 2 ‘Siêu’ Dân Biểu Của Triều Ngô: Hồi Ký Đỗ Mậu (Ngô Đình Nhu and Trần Lệ Xuân 2 ‘Super’ Congressmen of the Ngô Family: Đỗ Mậu’s Memoir),” General Sciences Library of Ho Chi Minh City, 1991, https://phucvu.thuvientphcm.gov.vn/Viewer/EBook/375809. Accessed December 9, 2024.

[lxiii] Robert Templer, “Madame Nhu Obituary,” The Guardian, April 26, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/apr/26/madame-nhu-obituary#:~:text=Madame%20Nhu%2C%20the%20name%20by,Total%20power%20is%20totally%20wonderful.%22. Accessed January 29, 2025.

[lxiv] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 154-156.

[lxv] “Memorandum From the Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (Hughes) to the Secretary of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, September 6, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d68. Accessed January 6, 2025.

[lxvi] “Central Intelligence Agency’s Memorandum of the Situation in South Vietnam,” National Security Archive, November 2, 1963, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB101/vn24.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2024.

[lxvii] Itkowitz, “‘The Dragon Lady’.”

[lxviii] Zein Nakhoda, “South Vietnamese Buddhists Initiate Fall of Dictator Diem, 1963” Global Nonviolent Action Database, April 19, 2010, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/south-vietnamese-buddhists-initiate-fall-dictator-diem-1963. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxix] “Memorandum of Conversation Between the Director of the Vietnam Working Group (Kattenburg) and Madame Tran Van Chuong,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, September 16, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d118. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[lxx] Marguerite Higgins, Our Vietnam Nightmare (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 62.

[lxxi] “Telegram From the Department of State to the Embassy in Vietnam,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 5, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d245. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[lxxii] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 10, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d250. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxxiii] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, June 8, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d157. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[lxxiv] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 10, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d250. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxxv] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 24, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d273. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxxvi] “Telegram From the Central Intelligence Agency Station in Saigon to the Agency,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, September 2, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d47. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[lxxvii] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume II, Vietnam, 1962, Office of the Historian, March 20, 1962, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v02/d118. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxxviii] “Memorandum of Conference With the President,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, September 6, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d66. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[lxxix] Itkowitz, “‘The Dragon Lady.’”

[lxxx] Heather Marie Stur, Beyond Combat: Women and Gender in the Vietnam War Era (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 30.

[lxxxi] Paul B. Fay, “Paul B. Fay, Jr. Oral History Interview – JFK #3, 11/11/1970,” by James A. Oesterle, John F. Kennedy Library Oral History Program (November 11, 1970): 200, https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/jfkoh-pbf-03. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxxxii] Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Caroline Kennedy, and Michael R. Beschloss, Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy (New York: Hyperion, 2011), 282, Kindle.

[lxxxiii] “Madame Nhu ‘Too Big For Her Britches’,” Internet Archive, October 7, 1963, https://archive.org/details/CIA-RDP65B00383R000200170012-1/mode/2up. Accessed January 10, 2025.

[lxxxiv] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 10, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d250. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[lxxxv] “U.S. and Diem’s Overthrow: Step by Step,” The New York Times, July 1, 1971, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/07/01/archives/us-and-diems-overthrow-step-by-step-pentagon-papers-the-diem-coup.html. Accessed January 10, 2025.

[lxxxvi] “Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume II, Vietnam, 1962, Office of the Historian, March 13, 1962, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v02/d106. Accessed January 10, 2025.

[lxxxvii] “Memorandum of Conversation,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Office of the Historian, October 2, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04/d168. Accessed January 10, 2025.

[lxxxviii] Joseph R. Gregory, “Madame Nhu, Vietnam War Lightening Rod, Dies,” The New York Times, April 26, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/27/world/asia/27nhu.html. Accessed December 9, 2024.

[lxxxix] Peter Brush, “Rise and Fall of the Dragon Lady,” HistoryNet, April 27, 2011, https://www.historynet.com/rise-and-fall-of-the-dragon-lady/. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[xc] Demery, Finding the Dragon Lady, 226.

[xci] Ibid., 38-39.

[xcii] Ibid.

[xciii] Gregory, “Madame Nhu.”

[xciv] Ngô-Đình, Ngô-Đình, and Willemetz, Viên Sỏi Trắng (The White Stone), 25.

[xcv] “Telegram From the Central Intelligence Agency Station in Saigon to the Agency,” FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January-August 1963, Office of the Historian, August 24, 1963, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d275. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[xcvi] Nguyen, Hanoi’s War, 180-181.

[xcvii] Ibid., 173.

[xcviii] “Voice of the Vietcong in Paris,” The New York Times, September 18, 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/18/archives/voice-of-the-vietcong-in-paris.html. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[xcix] “‘Sứ Giả Hòa Bình’ Trên Bàn Đàm Phán Hiệp Định Paris (‘Messenger of Peace’ At the Paris Agreement Negotiation Table),” Vietnam Women’s Union, January 17, 2023, https://hoilhpn.org.vn/tin-chi-tiet/-/chi-tiet/-su-gia-hoa-binh-tren-ban-%C4%91am-phan-hiep-%C4%91inh-paris-53309-1.html. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[c] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 140.

[ci] Ibid., 145.

[cii] Ibid., 124.

[ciii] “Nguyễn Thị Bình – Nhà Ngoại Giao Hàng Đầu (Nguyễn Thị Bình – Leading Diplomat),” Báo Cao Bằng, August 7, 2013, https://baocaobang.vn/-37677.html. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[civ] Odd Arne Westad, Chen Jian, Stein Tønnesson, Nguyen Vu Tung, and James G. Hershberg, “77 Conversations Between Chinese and Foreign Leaders on the Wars in Indochina, 1964-1977,” Woodrow Wilson International Center For Scholars (May 1998): 175, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/ACFB39.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2025.

[cv] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 16-17.

[cvi] Ibid., 134-135.

[cvii] Ibid., 22.

[cviii] Ibid., 148.

[cix] “Reflections of the ‘Viet Cong Queen,’” VietNamNet Global, February 16, 2013, https://vietnamnet.vn/en/reflections-of-the-viet-cong-queen-E66192.html. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[cx] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 229.

[cxi] “Vietcong Spokesman; Mrs. Nguyen Thi Binh,” The New York Times, November 4, 1968, https://www.nytimes.com/1968/11/04/archives/vietcong-spokesman-mrs-nguyen-thi-binh.html. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[cxii] “Madame Bình - Bộ Trưởng Việt Cộng Trên Bàn Đàm Phán (Madame Binh – Viet Cong Minister At the Negotiating Table),” Viet Nam Union of Friendship Organizations, March 8, 2024, https://vufo.org.vn/Madame-Binh---Bo-truong-Viet-cong-tren-ban-dam-phan-25-102401.html?lang=vn. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[cxiii] “Mrs. Binh Arrives For Visit in India,” The New York Times, July 19, 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/07/19/archives/mrs-binh-arrives-for-visit-in-india-vietcong-aide-met-by-reds-and.html. Accessed January 28, 2025.

[cxiv] Westad, Jian, Tønnesson, Nguyen, and Hershberg, “77 Conversations,” 173.

[cxv] Duy Trinh and Quang Vinh, “Ký Ức Sâu Đậm Của ‘Người Cận Vệ’ Già Về Bà Nguyễn Thị Bình (The Deep Memories of the Old ‘Bodyguards’ of Madame Nguyen Thi Binh),” Báo Tin Tức, January 25, 2023, https://baotintuc.vn/thoi-su/ky-uc-sau-dam-cua-nguoi-can-vegia-ve-ba-nguyen-thi-binh-20230125205732861.htm. Accessed January 25, 2025.

[cxvi] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 149.

[cxvii] Ibid., 151.

[cxviii] Ibid., 225.

[cxix] Ibid., 251.

[cxx] Ibid., 110.

[cxxi] Ibid., 143-144.

[cxxii] Ibid., 278.

[cxxiii] Hoàng Thuỳ and Nguyễn Hưng, “35 Năm Cuộc Chiến Biên Giới Phía Bắc (35 Years the Northern Border War),” VnExpress, February 14, 2014, https://vnexpress.net/35-nam-cuoc-chien-bien-gioi-phia-bac-2950346.html. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxxiv] Tào Nga, “Việt Nam Từng Có 1 Bộ Trưởng Giáo Dục Được Nhận Xét Là ‘Bậc Nữ Lưu Sáng Giữa Trời…’ (Vietnam Once Had a Minister of Education Who Was Considered a ‘Heroine That Shined in the Sky…’),” Báo Dân Việt, November 17, 2022, https://danviet.vn/cau-chuyen-ve-nu-bo-truong-giao-duc-nguyen-thi-binh-20221117112716934.htm. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxxv] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 274.

[cxxvi] Ibid., 275.

[cxxvii] Ibid., 272-273.

[cxxviii] Ibid., 298.

[cxxix] Phạm Văn Đồng, “Nghị Quyết Của Bộ Chính Trị Khoá IV về Cải Cách Giáo Dục (Resolution of the Fourth Politburo on Education Reform),” Báo điện tử Đảng Cộng Sản Việt Nam, January 11, 1979, https://dangcongsan.vn/doi-moi-can-ban-va-toan-dien-giao-duc-dao-tao/duong-loi-chinh-sach/nghi-quyet-cua-bo-chinh-tri-khoa-iv-ve-cai-cach-giao-duc-347269.html. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxxx] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 288.

[cxxxi] Ibid., 282.

[cxxxii] Nguyễn Thị Bình, Gia Đình, Bạn Bè Và Đất Nước - Hồi Ký Nguyễn Thị Bình (Family, Friends, and Country: Memoir)(Hà Nội: Tri Thức Publishing House, 2015), 234.

[cxxxiii] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 289.

[cxxxiv] Ibid., 288.

[cxxxv] Ibid., 289.

[cxxxvi] Ibid., 310.

[cxxxvii] Ibid., 289.

[cxxxviii] Đức Trung, “Ông Kim Ngọc Có Bị Kỷ Luật, Tù Tội? (Was Mr. Kim Ngoc Disciplined or Imprisoned?),” Báo Dân Trí, March 20, 2006, https://dantri.com.vn/xa-hoi/ong-kim-ngoc-co-bi-ky-luat-tu-toi-1142869947.htm. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxxxix] Đỗ Hữu Lực, “Truy Tặng Huân Chương Hồ Chí Minh Cho ‘Ông Khoán Hộ’ Kim Ngọc (Posthumously Awarded the Ho Chi Minh Medal to ‘Mr. Family Contracting’ Kim Ngoc),” Tuổi Trẻ Online, March 24, 2009, https://tuoitre.vn/truy-tang-huan-chuong-ho-chi-minh-cho-ong-khoan-ho-kim-ngoc-307733.htm. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxl] Lê Năng Đông, “Từ Quê Hương Quảng Nam Đến Hội Nghị Paris (From Hometown Quang Nam to the Paris Conference),” Trang thông tin điện tử Đảng bộ Tỉnh Quảng Nam, January 10, 2023, https://quangnam.dcs.vn/Default.aspx?tabid=109&Group=45&NID=9017&tu-que-huong-quang-nam-den-hoi-nghi-paris. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxli] Thu Phương, “50 Năm Hiệp Định Paris – Bài 3: Madame Bình - Bộ Trưởng Việt Cộng Trên Bàn Đàm Phán (50 Years the Paris Agreement – Article 3: Madame Binh – Viet Cong Minister at the Negotiating Table),” Báo Tin Tức, January 27, 2023, https://baotintuc.vn/thoi-su/50-nam-hiep-dinh-paris-bai-3madame-binh-bo-truong-viet-cong-tren-ban-dam-phan-20230127121802656.htm. Accessed January 26, 2025.

[cxlii] Nguyễn, Family, Friends, and Country, 324-325.

[cxliii] Ibid., 327-328.