1. Introduction

This article provides a general overview of ethnic nationalities, languages, scripts, linguistic relationships, language ecology, and other aspects of Vietnam. It also presents a detailed discussion of research conducted in Vietnam regarding the languages of "ethnic minorities."

2. Ethnic Nationalities and Languages in Vietnam

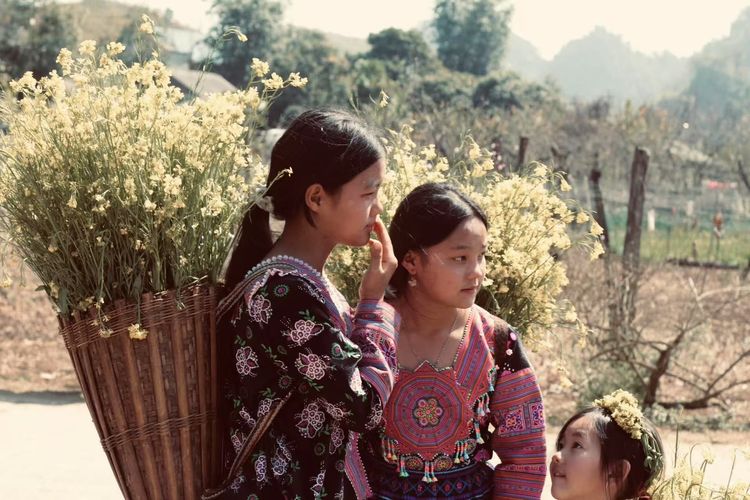

According to the 2009 census, Vietnam has 54 ethnic nationalities with a total population of 85,846,997 people. These include: Kinh, Tày, Thái, Mường, Khmer, Hmông, Nùng, Hoa, Dao, Gia Rai, Ê Đê, Ba Na, Sán Chay, Chăm, Cơ Ho, Xơ Đăng, Sán Dìu, Hrê, Ra Glai, Mnông, Xtiêng, Thổ, Bru - Vân Kiều, Khơ Mú, Cơ Tu, Giáy, Ta Ôi, Mạ, Gié - Triêng, Co, Chơ Ro, Xinh Mun, Hà Nhì, Chu Ru, Lào, Kháng, La Chí, Phù Lá, La Hủ, La Ha, Pà Thẻn, Lự, Ngái, Chứt, Lô Lô, Mảng, Cơ Lao, Bố Y, Cống, Si La, Pu Péo, Rơ Măm, Brâu, and Ơ Đu.

Among these 54 ethnic nationalities, the Kinh people comprise 73,594,427 individuals, accounting for 85.6% of the total population, making them the "majority ethnic group." The remaining 53 ethnic nationalities have a total population of 12,252,570 people, constituting 14.4% of the total population, and are classified as "ethnic minorities."

In Vietnam, language is a crucial criterion for distinguishing ethnic nationalities. According to common understanding, each of the 54 ethnic nationalities corresponds to a specific language. However, the actual number of languages spoken in Vietnam exceeds 54, as some ethnic peoples have subgroups that speak different languages. In total, Vietnam is home to over 90 languages.

3. Genetic Relationships and Typological Classification of Languages in Vietnam

3.1. Genetic Relationships

According to widely accepted views, the ethnic groups in Vietnam speak languages belonging to five major language families:

3.2. Typological Classification of Languages in Vietnam

All languages spoken in Vietnam belong to the same typological category: the isolating language type.

Isolating languages (also referred to as "non-inflectional languages") have several distinctive characteristics that make them easily recognizable:

The isolating languages in Vietnam can be divided into three subcategories:

Typological changes such as increased mono-syllabication and the development of tonal systems are common evolutionary trends among Vietnamese languages.

Additionally, Vietnam exhibits various sociolinguistic relationships, including:

(i) The relationship between Vietnamese—the national language—and minority languages.

(ii) The relationships between different ethnic minority languages.

(iii) The relationships between different dialects within the same ethnic group.

(iv) The relationships between cross-border languages (Vietnamese-Chinese, Vietnamese-Lao, Vietnamese-Khmer, etc.).

These relationships result from historical, national, and regional factors, as well as socio-economic, political, and cultural influences. However, the primary causes are historical wars, migration and immigration, territorial divisions and mergers, interspersed settlement patterns, ethnic fragmentation, and convergence or dispersion of ethnic nationalities.

4. Writing Systems of Ethnic Nationalities in Vietnam

Among the ethnic groups in Vietnam, many communities have developed their own writing systems. Some ethnic nationalities possess multiple scripts, while others have yet to develop one. Certain scripts have a history spanning nearly a thousand years, whereas others have been created more recently, based on the Latin alphabet. These scripts may be logographic, phonographic, or a combination of both.

In general, Vietnam has two main types of writing systems:

(1) Traditional writing systems: These scripts have been in use for centuries, including Classical Chinese (Chữ Hán), Vietnamese Nôm script (Chữ Nôm), Traditional Cham script, Khmer script, Tày Nôm, Nùng Nôm, Ngạn Nôm, Dao Nôm, Sán Chí Nôm, Sán Dìu Nôm, Lự script, and Old Thái script. These writing systems belong to ethnic groups such as the Khmer, Thái, Cham, Tày, Nùng, and Dao. The Old Thái, Traditional Cham, and Khmer scripts are derived from Sanskrit-based writing systems. Meanwhile, the traditional scripts of the Tày, Nùng, Cao Lan, Ngạn, and Dao (as well as the Nôm script of the Kinh people) belong to the category of "square scripts," originating from Classical Chinese and carrying a tradition of several centuries.

(2) "New" writing systems (Latin-based scripts): These are scripts developed using the Latin alphabet, including Quốc Ngữ (the modern Vietnamese script), as well as the scripts for the Ba Na, Gia Rai, Ê Đê, Cơ Ho, Pa Cô-Ta Ôi, Gié-Triêng, Bru-Vân Kiều, Cơ Tu, Ra Glai, Tày–Nùng, Mường, Thái, and others. The Latin-based scripts for Vietnam’s ethnic minorities were created during different historical periods. Some, like those for Ba Na, Gia Rai, Ê Đê, and Cơ Ho, were developed before 1945, while most were introduced after 1960.

5. Studies on the Languages (Speech and Writing) of Ethnic Nationalities in Vietnam

Since Vietnamese is the national language with the largest number of speakers, it has been extensively studied in diverse ways. The following section focuses only on research related to the languages of ethnic minorities.)

5.1. Before 1954

Alongside research on the Vietnamese language, scholars from the French School of the Far East (École française d'Extrême-Orient, EFEO) conducted studies on several ethnic minority languages in Vietnam.

The EFEO is a French research center specializing in Oriental studies, with a primary focus on fieldwork. Throughout its more than a century of existence, the EFEO has achieved significant accomplishments in the field of Asian studies. Its research journal, Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (BEFEO), has become well-known among scholars of archaeology and Asian history.

The EFEO’s first headquarters was established in Saigon, Cochinchina, in 1900. In 1902, its main office was moved to Hanoi, where it undertook archaeological excavations, collected manuscripts, preserved historical structures, and conducted research on ethnology, linguistics, and the history of Asian countries. The early years of the EFEO were marked by contributions from renowned scholars and leading figures in Oriental studies, including Paul Pelliot, Henri Maspero, and Paul Demiéville in linguistics; Louis Finot and George Cœdès in the epigraphy of Indochina; Henri Parmentier in archaeology; and Paul Mus in the study of religious history.

Currently, the EFEO archives still contain research materials on the Vietnamese, Cham, Ba Na, Mnông, Cơ Ho, and Gia Rai languages, as well as the writing systems of these ethnic nationalities.

Some writing systems were developed before 1945, such as those of the Ê Đê, Gia Rai, and Ba Na people. These scripts were created by missionaries and were used for religious propagation, becoming widely known among ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands. Although they had been in use since the 1920s, it was not until 1935 that the Governor-General of Indochina issued a decree officially recognizing the Ê Đê script and allowing its use in daily life. This script underwent certain modifications in 1937.

Later, particularly in the late 1980s, some individuals advocated for further simplifications in the script’s alphabet system to make it more suitable for printing and publishing Ê Đê-language books and materials.

Several other scripts and transcription methods from the French colonial period—such as those for Hmông, Mnông, Chăm, Cơ Ho, Ra Glai, and even the early versions of the Vietnamese quốc ngữ script—are no longer in use today. However, they have served as valuable references for the development of new writing systems in later years.

5.2. From 1954 to 1975

This was a period when Vietnam was divided into two regions: North and South.

In the North, the task of researching the languages of ethnic minorities was mainly assigned to the Institute of Linguistics (under the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences). Additionally, some universities and the Institute of Educational Sciences also conducted research on various aspects of ethnic minority languages. The Tày-Nùng script and the Hmông script were developed and officially introduced in 1961, used in bilingual education and for publishing some materials. Several studies were published, covering both fundamental research and practical applications, such as Grammar of the Tày-Nùng Language (1971), Understanding the Languages of Vietnam’s Ethnic Minorities (1972), Mèo-Vietnamese Dictionary (1971), and Tày-Nùng-Vietnamese Dictionary (1974).

The Institute of Linguistics (established in 1968, English name: Institute of Linguistics) had the function of researching fundamental theoretical and applied linguistic issues related to the Vietnamese language, ethnic minority languages, and foreign languages in Vietnam. It provided scientific arguments for language policy planning and offered consultation and postgraduate training in linguistics.

In the South, from 1957 onwards, there were research activities focused on the languages of ethnic minorities, the creation of writing systems, bilingual education, and religious missions.

The SIL International (Summer Institute of Linguistics), headquartered in Dallas, Texas, USA, aimed primarily at researching and documenting languages—especially lesser-known ones—to expand linguistic knowledge, promote literacy, translate the Christian Bible into local languages, and support minority language development. In 1957, this organization began operations in South Vietnam, studying ethnic minority languages, developing writing systems, translating the Bible for Protestant missionary work, and compiling bilingual teaching materials (such as textbooks and comparative vocabularies). Bilingual education programs were implemented, leading to the publication of numerous religious texts and schoolbooks in minority languages.

As a result, from the arrival of David Thomas, the first SIL representative in Vietnam, until the end of a 17-year period, numerous writing systems were developed, and a vast number of bilingual educational materials were prepared. Teaching materials were developed for languages such as Ba Na, Bru-Vân Kiều, Chu Ru, Cơ Ho, Ê Đê, Mnông, Nùng, Ra Glai, Rơ Ngao, Xơ Đăng, Xtiêng, Thái, Cơ Tu, Hroi, and Mường. From 1967, SIL provided these materials for primary school students, starting with reading and writing in their mother tongue before gradually integrating Vietnamese (bilingual education). The goal was to transition reading skills from the native language to Vietnamese. Between 1967 and 1975, around 800 to 1,000 teachers (mostly native speakers) were trained to teach using these materials.

A range of linguistic tools (dictionaries and vocabularies) was compiled based on these writing systems. Some of these systems were later modified (e.g., Gia Rai, Ba Na, Ê Đê). Examples of such works include: Học tiếng Ê Đê (Learning Ê Đê, Nguyễn Hoàng Chừng, 1961), Thổ Dictionary, Thổ - Vietnamese - English (A. C. Day, 1962), Ê Đê - French and French - Ê Đê Dictionary (R.P. Louison Benjamin, 1964), Sedang Vocabulary (Kenneth D. Smith, 1967), Mnong Rơlơm Dictionary (Henry Blood, 1976), Klei hriăm boh blu Ê Đê - Ê Đê Vocabulary (Y Cang Niê Siêng, 1979), Chù chìh dò tơtayh Jeh - Jeh Vocabulary (Patrick D. Cohen, 1979), A Rhade - English Dictionary with English - Rhade Finderlist (James A. Tharp & Y Bhăm, 1980), Katu Dictionary: Katu - Vietnamese - English (N.A. Costello, 1991)

These works were supplemented by grammar guides and articles describing the linguistic structures of these languages, often using the scripts of the respective ethnic nationalities.

Before 1975, the work of developing and promoting writing systems was not limited to SIL; it was also undertaken by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. The Front’s officers developed scripts for Cơ Tu, Xơ Đăng, Bru-Vân Kiều, Pa Cô, Hrê, Co, Mnông, Xtiêng, and improved the scripts for Ba Na, Ê Đê, and Gia Rai. They also promoted and implemented the use of these scripts among ethnic minority communities.

5.3. The Period from 1975 to the Present

This is the period of a unified Vietnam.

In 1981, the Latin-based Thai script was developed. In addition to creating new scripts, responsible institutions also improved several existing scripts, such as the Koho script (in Lâm Đồng), the Bru - Vân Kiều, Pa Cô - Ta Ôi scripts (in Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, Thừa Thiên - Huế), the Raglai script (in Ninh Thuận), the Cotu script (in Quảng Nam), the Chăm Hroi script, the Ba Na Kriêm script, the Hrê script (in Bình Định), the Mnông script (in Đắk Nông, Đắk Lắk), and the Ca Dong (Xơ Đăng) script in Quảng Nam, among others.

Numerous publications have been released, including Ngữ pháp tiếng Cơ ho (Grammar of the Koho language, 1985), Tiếng Pu Péo (1992), Tiếng Rục (1993), Những vấn đề chính sách ngôn ngữ ở Việt Nam (Issues in Language Policy in Vietnam, 1993), Ngữ âm tiếng Êđê (Ede Phonetics, 1996), Tiếng Ka tu: Cấu tạo từ (Katu Language: Word Formation, 1995), Tiếng Mnông - ngữ pháp ứng dụng (Mnong Language - Applied Grammar, 1996), Tiếng Ka tu (Katu Language, 1998), Tiếng Bru - Vân Kiều (Bru - Vân Kiều Language, 1998), Tiếng Hà Nhì (Hà Nhì Language, 2001), Cảnh huống và chính sách ngôn ngữ ở Việt Nam (Language Situation and Policy in Vietnam, 2002), Ngữ âm tiếng Cơ ho (Koho Phonetics, 2004), Tiếng Mảng (Mang Language, 2008), Ngữ pháp tiếng Cơ tu (Grammar of the Cotu Language, 2011), Ngữ pháp tiếng Êđê (Grammar of the Ede Language, 2011), Ngữ pháp tiếng Cor (Grammar of the Cor Language, 2014), Ngôn ngữ các dân tộc ở Việt Nam (Languages of Ethnic Groups in Vietnam, 2017), and Ngữ pháp tiếng Hmông (Grammar of the Hmong Language, 2019), among others.

Multilingual bilingual dictionaries have also been compiled, such as Từ điển Việt - Gia Rai (Vietnamese - Jarai Dictionary, 1977), Từ điển Việt - Cơ ho (Vietnamese - Koho Dictionary, 1983), Từ điển Việt - Tày - Nùng (Vietnamese - Tay - Nung Dictionary, 1984), Từ điển Thái - Việt (Thai - Vietnamese Dictionary, 1990), Từ điển Việt - Êđê (Vietnamese - Ede Dictionary, 1993), Từ điển Việt - Mông (Việt - Hmôngz) (Vietnamese - Hmong Dictionary, 1996), Từ vựng các phương ngữ Êđê (Ede Dialect Vocabulary, 1998), Từ điển Cơ tu - Việt, Việt - Cơ tu (Cotu - Vietnamese, Vietnamese - Cotu Dictionary, 2007), Từ điển Êđê - Việt (Ede - Vietnamese Dictionary, 2015), and Từ điển Việt – Cor, Cor – Việt (Vietnamese - Cor, Cor - Vietnamese Dictionary, 2024).

Many textbooks for learning and teaching ethnic minority languages have been published, such as Sách học tiếng Pakôh - Taôih (Pakoh - Taoi Language Textbook, 1986), Hdruôm hră hriăm klei Êđê (1988), Sách học tiếng Bru - Vân Kiều (Bru - Vân Kiều Language Textbook, 1986), Sách học tiếng Êđê (Ede Language Textbook, 1988), Hdruôm hră hriăm klei Êđê (2004), Pơrap Kơtu (Cotu Language, 2006), Bôq chù Hrê Bình Định (Hrê Script in Bình Định, 2008), and Xroi Kool - Tiếng Cor (Cor Language, 2014).

Following Decision 53 - CP of the Council of Ministers of Vietnam (February 22, 1980) on policies regarding ethnic minority scripts, ethnic minority intellectuals, and Vietnamese linguists worked to refine the scripts for Koho, Co, Hrê, Ba Na, Raglai, Mnông, Xơ Đăng, Cotu, Ca Dong, etc. These scripts were then used to compile textbooks, bilingual dictionaries, grammar books, and instructional materials. Many works of folklore, including customary laws, epics, and folktales, were collected, translated, and published in these scripts.

Numerous literary works and informational books in bilingual Vietnamese - ethnic minority formats have been widely disseminated across the country, including Sóng chụ son sao (Thai ethnic group), Tiếng hát làm dâu (Hmong people), Đăm San, Xinh Nhã (Ede people), Người Mông nhớ Bác Hồ, Chỉ vì quá yêu (Hmong people), Luật tục dân tộc Gia Rai (Jarai Customary Law), Luật tục dân tộc Mnông (Mnong Customary Law), and Văn vĩ quan làng (Tay people). In recent years, the epics of ethnic nationalities in the Trường Sơn and Central Highlands regions, such as the Xtriêng, Raglai, Mnông, Jarai, Ede, and Ba Na epics, have been collected and published bilingually.

In education, by 2025, eight ethnic minority languages—Thai, Hmong, Ba Na, Jarai, Xơ Đăng, Chăm, Khmer, Hoa, and Ede—have been incorporated into primary and ethnic boarding school curricula. Many textbooks in ethnic minority languages or bilingual ethnic minority - Vietnamese formats have been developed.

In mass media, since 1956, the Voice of Vietnam (VOV) has broadcast in ethnic minority languages such as Jarai, Ba Na, Ede, Hrê, Mnông, and Châu Mạ, followed by Thai, Hmong, Mường, and others. By 2025, nearly 30 ethnic minority languages have been broadcast on VOV4 radio and VTV5 television. Provinces with large ethnic minority populations also have radio and television programs in ethnic minority languages, including Khmer, Chăm, Ede, Jarai, Ba Na, Cotu, Koho, Xơ Đăng, Xtriêng, Thai, Mường, Dao, Hmong, Mnông, Hrê, Châu Ro, Bru-Vân Kiều, Ta Ôi, and Raglai.

Regarding research cooperation, many foreign scholars from Russia, the United States, China, France, and other countries have conducted research in Vietnam.

Since the 1990s, within the framework of Vietnam - Soviet (later Vietnam - Russia) cooperation, the Vietnam - Soviet (later Vietnam - Russia) field survey program on ethnic minority languages in Vietnam has investigated many languages, providing data for the compilation of field research materials, including Tiếng La Ha (Laha Language, 1986), Tiếng Mường (Muong Language, 1987), Tiếng Kxinhmul (Kxinhmul Language, 1990), Tiếng Pu Péo (Pu Péo Language, 1992), Tiếng Rục (Rục Language, 1993), and Tiếng Cơ Lao (Cơ Lao Language, 2011).

6. Conclusion

Vietnam is a multi-ethnic and multilingual country.

Many ethnic minority languages in Vietnam have been studied. The directions for future research include:

However, many languages and aspects of languages in Vietnam have not been fully researched. The list of languages spoken in Vietnam today is still provisional. There is no effective or feasible method yet for language education in ethnic minority areas. An effective solution to the deterioration of languages with lower status and fewer speakers in the current conditions of Vietnam has not been found. Some languages are already disappearing, and there are languages that have become dead languages.

On this note, I would like to share the comment of the author René Gillouin (from his book From Alsace to Flanders: The Mysticism of Linguistics - quoted by Phạm Quỳnh [8]):

“For a people, losing their mother tongue is like losing their soul.”

Bibliography

Baker, Colin (2008), Những cơ sở của giáo dục song ngữ và vấn đề song ngữ , Nxb. Đại học Quốc gia TP. Hồ Chí Minh, TP. Hồ Chí Minh.

Gregerson, Marilin (1989), “Ngôn ngữ học ứng dụng: Dạy đọc chữ (tài liệu cho các ngôn ngữ thiểu số)”, Tạp chí Ngôn ngữ, số 4.

Hồng, Nguyễn Quang (2018), Ngôn ngữ. Văn tự. Ngữ văn, Nxb Khoa học Xã hội, H.

Lợi, Nguyễn Văn (1995), “Vị thế tiếng Việt ở nước ta hiện nay”, Tạp chí Ngôn ngữ, số 4.

Lợi, Nguyễn Văn (2012), “Công trình tra cứu về ngôn ngữ và vấn đề bảo tồn ngôn ngữ có nguy cơ tiêu vong”, Tạp chí Từ điển học & Bách khoa thư, s. 2(16).

Solncev V.M... [1982], "Về ý nghĩa của việc nghiên cứu các ngôn ngữ phương đông đối với sự phát triển của ngôn ngữ học đại cương", Ngôn ngữ số 4.

Tuệ, Hoàng... (1984), Ngôn ngữ các dân tộc thiểu số Việt Nam và chính sách ngôn ngữ, Nxb. Khoa học xã hội, H.

Quỳnh, Phạm (2007), Tiểu luận (viết bằng tiếng Pháp trong thời gian 1922 – 1932), Nxb. Tri thức, H.

Thông, Tạ Văn (1993), “Mối quan hệ giữa chữ và tiếng các dân tộc thiểu số với chữ và tiếng Việt”, Trong: Những vấn đề chính sách ngôn ngữ ở Việt Nam, Nxb. Khoa học Xã hội, H.

Thông, Tạ Văn – Tùng, Tạ Quang (2017), Ngôn ngữ các dân tộc ở Việt Nam, Nxb. Đại học Thái Nguyên.

Tổ chức Giáo dục, Khoa học và Văn hóa của Liên Hợp Quốc UNESCO Băng Cốc (2007), Tài liệu hướng dẫn Phát triển Chương trình Xóa mù chữ và Giáo dục cho người lớn tại cộng đồng ngôn ngữ thiểu số, NXB Giao thông Vận tải, H.

China and Vietnam share a landscape of interconnected mountains and rivers. Throughout a long historical evolution, Chinese individuals have migrated to Vietnam and established permanent residence due to various political, economic, and other factors. Both historically and in contemporary times, the Chinese community has made significant contributions to Vietnamese culture, the economy, and other sectors.

Following their migration to Vietnam, the Chinese brought with them advanced scientific and technological knowledge as well as rich cultural traditions, which have exerted a profound and lasting influence on Vietnamese society.

This study focuses on the period from the late 17th century to the mid-19th century, aiming to examine the contributions of the Chinese community in Vietnam to the country’s economic development during this time. It is hoped that this research will enhance understanding of the vital role played by the Chinese in Vietnamese society and contribute to the promotion of friendly relations between China and Vietnam.

1. An Overview of the Chinese Community in Vietnam

According to Vietnam's official classification of ethnic groups, the Chinese community in Vietnam includes not only a considerable number of Han (Hua) people and Ngái people, but also individuals whose ancestors came from China and belong to 21 other ethnic groups. These include the Tay, Nung, Bouyei, Giay, San Diu, Lach, Hmong (Miao), Yao, Pa Then, La Chi, Bo Y, Ha Nhi, Lahu, Lolo, Phu La, Co Lao, Mang, Cong, Si La, Khang, and Kmu, among others. These groups are intricately linked to the Miao-Yao and Zhuang-Dong language families in China and share deep historical and cultural connections with many of the ethnic groups recognized in contemporary China. A significant number of them are Chinese immigrants who relocated to Vietnam after the establishment of the Vietnamese nation.

The migration of overseas Chinese into Vietnam occurred through two primary modes: voluntary migration and forced migration. Voluntary migration was mainly driven by reasons such as livelihood pursuits, commercial activities, failure to return from military campaigns, and religious pilgrimages. Forced migration, on the other hand, was largely caused by factors including political turmoil within China, coercion by foreign powers, and separatist forces in Vietnam, as well as human trafficking. The migration routes were primarily divided into land and maritime pathways. The land routes can be categorized as follows: first, from Thailand along the Mekong River into northwestern Vietnam; second, from Xishuangbanna in Yunnan Province, China into Vietnam, which further subdivides into two branches—one following the Red River to reach Lao Cai and Yen Bai in Vietnam, continuing northwards to the midland areas, then turning towards the areas of Yilu and Shanluo; the other branch followed the Tuo River, eventually settling in places such as Fengtu and Qiongya. Additionally, some migrants crossed the land border directly between China and Vietnam. The migrants from Guangdong and Fujian provinces primarily migrated by sea, crossing the Qiongzhou Strait and traversing the Gulf of Tonkin into Vietnam. Over time, as Vietnamese society underwent continuous transformation, these Chinese immigrants expanded their presence from northern Vietnam into the central and southern regions. Moreover, a certain number of Chinese migrants directly crossed the Gulf of Tonkin to enter central and southern Vietnam.

Chinese immigrants who entered Vietnam maintained intricate and enduring ties with China. Since ancient times, Vietnam has had close relations with China and has been deeply influenced by Chinese Confucian culture. Consequently, culturally, these Chinese immigrants retained a strong sense of cultural identity with China and Confucianism after migrating to Vietnam. Economically, through arduous efforts in Vietnam, the Chinese immigrants achieved significant success and acquired considerable economic strength. Around the time of the Opium Wars, the occupations of overseas Chinese in Vietnam became increasingly diversified, with their presence evident across almost all economic sectors. The majority of overseas Chinese engaged in commerce and industry. Many were owners of small and medium-sized enterprises or small traders involved in rice milling, sugar production, cotton processing, textiles, shipbuilding, brewing, oil pressing, tobacco, food processing, ceramics, medicine, mining, chemical industry, condiments, tea, electrical appliances, machinery, dried fish, steel smelting, and other industries.

It is evident that in areas with concentrated overseas Chinese populations, commerce and industry were relatively well developed. In the early twentieth century, the city of Saigon (then with a total population of 94,000, of whom 49,000 were overseas Chinese, accounting for more than half of the total population) had become the largest commercial center in Vietnam at the time. Moreover, numerous overseas Chinese who began as clerks, laborers, farmers, and fishermen rose to become capitalists, possessing substantial capital and considerable economic power.

By the early twentieth century, the total population of overseas Chinese in Vietnam had reached a significant scale, numbering over one million, ranking sixth among the ethnic groups within the broader Vietnamese national family. The distribution of the Vietnamese Chinese population was widespread, with communities residing across mountainous regions, plains, cities, and rural areas throughout the country. Among the more than one million overseas Chinese, approximately 80% traced their ancestral origins to Guangdong Province, while about 20% came from Fujian, Yunnan, Guangxi, and other provinces. The majority of the Chinese population resided in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly known as Saigon), where the Chinese community numbered 524,499 individuals. Additionally, several provinces in southern Vietnam had Chinese populations exceeding ten thousand, including Hau Giang (102,571), Dong Nai (84,570), Minh Hai (40,144), Song Be (32,512), Cuu Long (20,898), Kien Giang (20,638), and An Giang (18,617). In northern Vietnam, there were approximately 300,000 overseas Chinese, with Quang Ninh Province alone accounting for around 180,000, Haiphong City more than 50,000, and Hanoi 4,015.

During the more than two centuries from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, overseas Chinese in Vietnam experienced two major waves of migration: one occurring during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, and another following the Taiping Rebellion. The number of overseas Chinese migrating to Vietnam has steadily increased. Relying on their intelligence and hard work, they made substantial contributions to the development of Vietnam’s socio-economic landscape. Notably, the period from the late seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth century stands out as a particularly significant historical era.

2. An Analysis of the Background of Chinese Immigration to Vietnam from the Late 17th to the 19th Century

From the late 17th century to the mid-19th century, both China and Vietnam underwent dynastic transitions but continued to exist as agrarian societies, each cultivating its own flourishing agricultural civilization. On the Chinese side, following the dynastic shift from the Ming to the Qing, the Qing gradually consolidated its rule over the entire country. By the late 17th century, it had suppressed the Revolt of the Three Feudatories and reclaimed Taiwan. In the mid-19th century, Western powers began penetrating China, gradually transforming it into a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society. Sharp class contradictions emerged, leading to frequent peasant uprisings.

On the Vietnamese side, during the late 17th century, the country was nominally under the rule of the Later Lê dynasty (1428–1788). In reality, however, Vietnam was politically divided between two feudal powers: the Trịnh lords in the North, centered in Thăng Long (present-day Hanoi), and the Nguyễn lords in the South, based in Thuận Hóa. Both the Trịnh and Nguyễn lords nominally pledged allegiance to the Lê emperor. In 1771, the Tây Sơn uprising broke out. This large-scale peasant rebellion successively overthrew the Nguyễn and Trịnh regimes and in 1788 abolished the Later Lê dynasty, establishing the Tây Sơn regime. Nguyễn Huệ ascended the throne under the reign title Quang Trung. In 1802, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, a descendant of the Nguyễn lords, defeated the Tây Sơn regime and established the Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1945). During the reigns of Gia Long (1802–1820) and Minh Mạng (1820–1841), Vietnam experienced a period of national strength and economic prosperity.

However, in 1858, during the reign of Emperor Tự Đức (1847–1883), French colonial forces arrived in Vietnam. Their growing influence threatened not only Vietnam's independence and national sovereignty but also disrupted the tribute system in East Asia, which had traditionally centered on China. Violent clashes between Eastern and Western forces ensued in Vietnam.

Within this historical context, large-scale Chinese migration to Vietnam occurred, contributing to the formation of a substantial Chinese-Vietnamese population during this period. These migrants were primarily composed of remnants of the Ming loyalists, merchants, miners, members of peasant insurgent forces, and secret society affiliates. Over time, to better survive and integrate into local life, a portion of these migrants gradually assimilated into Vietnamese society, becoming Vietnamese Chinese.

In contrast to the aggressive expansion of Western colonialists, overseas Chinese in Vietnam were more characterized by the Confucian virtues of benevolence, respectfulness, frugality, and humility. They made significant contributions to the social and economic development of Vietnam.

3. The Economic Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Vietnam from the Late 17th to the Mid-19th Century

Following their migration to Vietnam, Chinese immigrants made significant contributions to the country’s development at various historical stages through their industrious labor, scientific and cultural knowledge, and accumulated practical experience. Among these contributions, their economic impact was particularly prominent. Between the late 17th century and the mid-19th century, Chinese immigrants greatly facilitated the early economic development of Vietnam. They brought with them relatively advanced agricultural techniques from China and possessed rich experience in navigation and trade. Utilizing these skills and knowledge, they worked alongside local inhabitants to develop and build their new homeland. Their contributions were substantial in agriculture, land reclamation, port construction, mining development, and road building.

3.1. In the Field of Agriculture

As early as 1679 (the 18th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign), Chen Shangchuan (*) led more than 3,000 soldiers and their families aboard over 50 warships to southern Vietnam, seeking refuge with the Nguyễn lords in Huế. Nguyễn Phúc Tần received them warmly, retained their naval structure, conferred official titles upon them, and resettled them in the Đông Phố region to engage in agricultural and developmental work. Chen Shangchuan and his followers reclaimed wasteland and established settlements along the Đại Phố islet of the Đồng Nai River. For over a decade, they carried out development activities deeply infused with the cultural traditions and styles of the late Ming Dynasty.

Chen actively attracted Chinese merchants to establish streets and markets, drawing overseas Chinese to the area and inviting merchants from various countries, thereby transforming Đồng Nai into a major metropolis and commercial center of southern Vietnam. Originally a sparsely populated wilderness, the area saw rapid population growth, reaching over 40,000 households by 1698, the vast majority of which were Chinese. Chen later led development efforts along the Mekong River for another eight years, playing a vital role in the construction and prosperity of the newly reclaimed areas. Thanks to the tireless efforts of overseas Chinese and local residents, the Tiền Giang and Hậu Giang regions became known as the "land of fish and rice" by the early 19th century.

Chinese immigrants also made notable contributions to hydraulic engineering. They participated in the dredging and construction of major waterways, such as the An Thông River, Vĩnh Thanh River, and Rui River. Due to the narrowness of the An Thông River, Emperor Gia Long of the Nguyễn dynasty ordered its expansion in 1819. Chinese immigrants played a crucial role in the successful execution of this project. Since the 17th century, through the relentless efforts of Chinese immigrants and local communities—digging canals, reclaiming land, developing agriculture, and building irrigation systems—the complex and disorganized Mekong Delta was gradually transformed into a fertile and prosperous agricultural region.

In northern Vietnam, especially near the Sino-Vietnamese border, many Chinese immigrants also engaged in agriculture within Vietnamese territory. For instance, in the early 18th century, migrants from Guangxi came to Vietnam to farm, reclaim land, and build irrigation systems. Many of the fields and dams were subsequently named after these Chinese settlers, such as Lu Luc Field, Lao Luu's Sluice, and Tang Nhi Dike in Quảng Hà District, Quảng Ninh Province. After the failure of the Taiping Rebellion, insurgent forces from Guangxi also migrated to Vietnam and took up farming. The Black Flag Army, during its operations in Vietnam, implemented agricultural garrison systems as well. These groups made considerable contributions to the development of local agriculture.

3.2. In the Commercial Sector

After migrating to Vietnam, Chinese immigrants, regardless of their reasons for migration or how they arrived, generally engaged in commercial activities once they had settled. This was largely due to Vietnam’s long-standing feudal structure and its predominantly agrarian economy, which offered limited occupational diversity. For overseas Chinese separated from their homeland, trade represented a relatively convenient means of livelihood.

Vietnam’s favorable geographic location, situated at the crossroads of East–West maritime trade routes, had long made it a hub for international commerce. In the South Seas trade network, Vietnam consistently played a significant role. During the period of conflict between the Trịnh and Nguyễn lords, the Nguyễn regime in Quảng Nam actively promoted foreign trade and vigorously recruited overseas merchants in the southern regions.

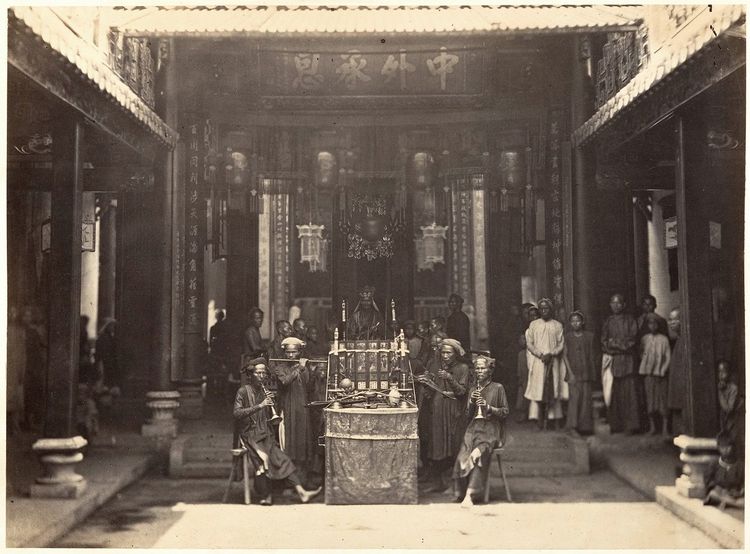

In his book The Chinese in Southeast Asia, Victor Purcell wrote: "In the latter half of the 16th century, when European traders arrived in Indochina, the king of the region of Giao Chỉ (modern-day southern Vietnam) allowed the Chinese to select a suitable location within his territory to establish a city and engage in trade. This city was Hội An, located in central-southern Vietnam today. The city was divided into two zones—one for the Chinese and one for the Japanese... After a seven-month-long trading season, the foreign merchants would depart with their goods."

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Chinese merchants gathered in Hội An, and foreign ships came and went regularly, giving rise to a flourishing commercial scene. By the late 17th century, Đại Đường Street in Hội An stretched three to four li (about 1.5–2 km). In 1768, the area of Hội An was home to approximately 6,000 Chinese residents, who made the commercial activities there especially vibrant.

In the early 18th century, the development of the Hà Tiên area by Mạc Cửu and his son transformed this once-barren land into a first-rate seaport. The efforts of Chinese immigrants in cultivating and developing the fertile lands of the Mekong Delta’s Tiền Giang and Hậu Giang regions laid the groundwork for the later commercial prosperity of what is now the Chợ Lớn district of Ho Chi Minh City and other southern border regions of Vietnam.

By the late 18th century, Chợ Lớn had begun to thrive. Many Chinese involved in overseas trade owned their own ships and operated across vast areas. After Nguyễn Phúc Ánh unified Vietnam in 1802, the majority of Chinese merchants gathered in Chợ Lớn to conduct business. By the early 19th century, Chợ Lớn had become Vietnam’s most prosperous city, bustling with merchants from all directions. The city was home to numerous Chinese guild halls, associations, and regional societies, as well as temples dedicated to Guan Yu and Mazu. For this reason, it earned the nickname "Overseas China."

Throughout the long history of migration and the pursuit of livelihood and development, Chinese immigrants in Vietnam primarily concentrated in southern cities where commercial economies were more developed. The rise and prosperity of certain cities were inextricably linked to the efforts and economic activities of the Chinese population. Once these urban centers emerged, they further attracted numerous Chinese merchants as well as Vietnamese traders from other regions.

By the 1820s, one-third of the approximately 315 Chinese commercial vessels that sailed abroad each year were bound for Vietnam. Chinese presence was common across the ports along the Annamese coast—from street vendors and wealthy merchants to shipowners and customs officials, Chinese individuals actively participated in all levels of the port economy. The port cities of Vietnam were bustling with goods, and much of the tea, medicine, and porcelain sold there was brought by Chinese vessels.

From the late 17th century to the mid-19th century, Vietnam experienced a golden age of maritime trade. Hội An, in particular, was a thriving commercial hub filled with an astonishing variety of goods. The Chinese played a key role in managing exports of local Vietnamese specialties such as raw and processed silk, ebony, agarwood, sugar, cinnamon, pepper, and rice. In return, Chinese imports included both coarse and fine porcelain, paper materials, tea, silverware, weaponry, and various Western goods. During the Qing dynasty, a significant number of Chinese merchants were engaged in overseas trade in Vietnam, forming a powerful and influential commercial force. Chinese individuals and their merchant vessels became an indispensable part of Vietnam’s economic development.

In addition to their contributions to maritime trade, Chinese immigrants also played a major role in the development of overland border trade between China and Vietnam. During the Qing dynasty, China’s relatively open trade policy allowed Chinese merchants to conduct cross-border trade. Vietnam, on its part, established border towns within its territory to facilitate commerce with Chinese traders. This form of trade exhibited two distinct features:

(a) Trade Flow: The predominant direction of trade involved exports of Chinese goods into Vietnam, with minimal Vietnamese exports entering China. Chinese goods, primarily everyday necessities, served not only the general Vietnamese population but also the roughly 25,000 Chinese miners working in northern Vietnam.

(b) Trade Participants: Most of the merchants engaged in cross-border trade were Chinese nationals or overseas Chinese, while many Vietnamese officials responsible for managing border trade were themselves of Chinese descent.

Hence, Chinese immigrants played a pivotal role in the growth and regulation of Sino-Vietnamese border commerce during this period.

In summary, from the late 17th century to the mid-19th century, Chinese merchants, most of whom operated as small-scale retailers, spread across both urban and rural areas of Vietnam, supplying a wide range of daily necessities. This widespread commercial activity underscores the substantial contribution of Chinese immigrants to Vietnam’s economic development during that era.

3.3. In the Field of Mining

From north to south, Vietnam is rich in mineral reserves and has a wide variety of resources. These abundant mineral resources had already been extensively exploited as early as the Later Lê Dynasty. Before the reign of Emperor Lê Hiển Tông (1740–1786), almost all areas in Tonkin (northern Vietnam) with deposits of gold, silver, copper, and lead had already seen the establishment of mining operations.

The growing demand for minerals prompted the Vietnamese government to implement proactive mining policies and to encourage foreign investment in the mining sector. Many Chinese responded positively to these government policies and flocked to Vietnam to invest in mining operations. The Vietnamese government often welcomed Chinese capital to help develop its mining economy.

To enhance management over the mining sector, successive Vietnamese dynasties attempted to limit the scale and number of mining operations. However, in reality, these restrictions were rarely effectively enforced, and most Chinese-run mines exceeded the officially permitted limits. The number of Chinese mine workers increased significantly.

During the Nguyễn Dynasty, advancements in mining technology and increased demand further expanded both the scope and scale of mining activities. At that time, the Nguyễn court also reformed its mining policies by strengthening governmental control over mining operations. One such reform required that all private mining ventures first submit an application to the government and assume tax obligations. This system was called the “tax farming system” (領徵制), and those granted the right to collect and pay taxes were referred to as “tax households” (稅戶). This policy reflected Vietnam's increasing emphasis on mining. Following this reform, Chinese mining entrepreneurs transitioned into tax households under the system.

Chinese contributions to the development of Vietnam’s mining sector not only helped meet the country’s growing demand for mineral resources but also provided substantial mining tax revenues to the feudal government. Meanwhile, the Chinese merchants involved in these ventures reaped significant profits.

The vigorous participation of overseas Chinese in Vietnam’s mining industry also stimulated the country's broader economic development, especially in remote mountainous regions. Northern Vietnam’s Sino-Vietnamese border areas were once economically underdeveloped, but since the launch of Chinese mining operations, hotels, taverns, clinics, and pharmacies have quickly sprung up, boosting local prosperity.

4. Conclusion

From the late 17th century to the mid-19th century, Chinese and overseas Chinese made significant contributions to the socio-economic development of Vietnam. Those who migrated to southern Vietnam worked hand in hand with the local population to develop and build the region, laying the foundation for the prosperity of today’s southern Vietnam.

Over time, in pursuit of better livelihoods, many Chinese migrants gradually integrated into Vietnamese society, eventually becoming an integral part of the Vietnamese nation. Their movement from China to Vietnam marked not just a migration between two neighboring countries, but a shift from one agrarian society to another—an internal flow within the broader framework of traditional agricultural civilization, involving the transfer of population, resources, and technological knowledge.

Carrying with them Confucian values such as benevolence, propriety, frugality, and humility, these migrants lived in harmony with the local communities. Through peaceful coexistence and diligent effort, they contributed significantly to Vietnam’s social, economic, and cultural development. In doing so, they helped shape a vibrant chapter in the history of Sino-Vietnamese relations.

Note:

(*) Chen Shangchuan (1626–1715) was a renowned Chinese expatriate leader who migrated to Vietnam during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. He is also considered one of the earliest overseas Chinese community leaders in Chinese history. He made outstanding contributions to promoting Sino-Vietnamese cultural exchange and was deeply admired and respected by both the local population and the Chinese immigrant community.

References

1. You, Jianshe. (2006). An Analysis of the Vietnamese Feudal Government's Policies Toward Chinese and Overseas Chinese from the Late 17th Century to the Mid-19th Century. Journal of Southwest China Normal University, (6), November.

2. Yang, Jiangfa. (1991). Recent Developments Among Overseas Chinese in Vietnam. Southeast Asian Studies, (1).

3 . Yan, Xing & Zhang, Zhuomei. (2002). The Chinese in Vietnam: History and Contributions. Journal of Wenshan Teachers’ College, 1(May).

4 . Tran, Trong Kim. (2005). A Brief History of Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh City: General Publishing House.

5. Dang, Nghiem Van. (2003). The Vietnamese National Community. Ho Chi Minh City: Vietnam National University Press.

6. Purcell, Victor. (1965). The Chinese in Southeast Asia. Oxford University Press.

The monograph The Everyday Politics of Resources: Lives and Landscapes in Northwest Vietnam by Associate Professor Nga Dao, Department of Social Sciences, York University (Canada), will be published by Cornell University Press on May 15, 2025.

This work offers a critical examination of the transformative effects of development initiatives—such as hydropower dams, rubber plantations, and mining operations—on the lives, livelihoods, and environments of communities in Northwest Vietnam. While these projects have generated significant profits for the state and private enterprises, they have also resulted in widespread displacement, impoverishment, and ecological degradation.

Drawing on more than two decades of in-depth ethnographic fieldwork, Professor Dao documents the highly uneven outcomes of these development processes. The monograph presents compelling narratives from individuals and communities who have faced dispossession and loss, alongside those who have adapted and, in some cases, benefited from these transformations. Through this nuanced analysis, The Everyday Politics of Resources provides an urgent and insightful contribution to debates on development, inequality, and environmental change in contemporary Vietnam.

We invite readers and scholars with interests in Southeast Asian studies, Vietnam Studies, development studies, anthropology, and political ecology to engage with this publication.

For more details, visit the official Cornell University Press page