1. Chinese Characters and Nôm Script

Although there are hypotheses in Vietnamese historical scholarship about an ancient script used by the Vietnamese people dating back three to four thousand years to the era of the Hùng Kings, the classical Vietnamese literary tradition that has been preserved to this day recognizes only Chinese characters (chữ Hán) and Nôm script (chữ Nôm) in its history of formation and development. Of course, to have a more comprehensive view of the literary heritage of the various ethnic communities that have long coexisted in present-day Vietnam, one must also consider other scripts, such as the Cham script in the South and the Tai script in the North. Nevertheless, the repository of Chinese and Nôm script literature remains the foundation of Vietnam’s classical literary tradition.

Chinese characters were introduced to the South quite early, possibly as far back as a few centuries BCE. With the establishment of the state of Nam Việt (207–111 BCE) by Triệu Đà, Chinese characters became the administrative tool for both the Han and the Vietnamese populations of the time. However, it was not until the early centuries CE, under the Han Dynasty, and with the active promotion of Han culture by governors such as Tích Quang, Nhâm Diên, and especially Sĩ Nhiếp, that Chinese characters truly became a functional tool for the Vietnamese. From then on, a class of local Vietnamese scholars and officials proficient in Chinese characters began to emerge. It is not by chance that Sĩ Nhiếp (186–266) was later honored as the "Patriarch of Learning in Giao Châu." However, written records of Chinese characters from that time, and even from the following several centuries in Vietnam, have not been preserved. The oldest surviving Chinese inscription in Vietnam is the Đại Tùy Cửu Chân Quận Báo An Đạo Tràng Chi Bi Văn stele, discovered in Đông Sơn District, Thanh Hóa Province. It was composed by Nguyễn Nhân Khí in the 14th year of the Đại Nghiệp era (618 CE) of the Sui Dynasty. The stele, measuring 75 cm × 150 cm, has faded inscriptions and is currently housed at the Vietnam National Museum of History.

Although Vietnamese and Chinese may originate from different language families (Sino-Tibetan for Chinese and Austroasiatic for Vietnamese), they are typologically very similar. Both are isolating and monosyllabic languages, meaning that each syllable generally carries meaning and can function as a word without morphological changes. Because of this, Chinese characters, representing both sound and meaning for each syllable, became an ideal script for writing Vietnamese at the time. Consequently, the transition from Chinese characters to Vietnamese script (Chữ Nôm) was relatively smooth. At first glance, a Chữ Nôm text can be difficult to distinguish from a Chinese text.

However, the development of Chữ Nôm was not immediate. Initially, individual characters were used sporadically to record local place names, personal names, and native products within Chinese texts. This practice likely began as early as the first century AD when Chinese characters were actively used by the Vietnamese not only for reading but also for recording events, people, and the local environment. However, it took a long time to establish a fully developed system of phonetic-semantic characters for Vietnamese. The challenge was not just the technical creation of characters but the prerequisite of national independence and the cultural need for a distinct script. It was not until the Đinh, Lê, Lý, and Trần dynasties (11th–14th centuries), when Vietnam had secured its independence and developed a strong national identity, that Chữ Nôm could emerge as a fully-fledged writing system. Vietnamese texts written in Chữ Nôm began to appear gradually.

According to historical records, the creation of Chữ Nôm is linked to the legend of Hàn Thuyên (also known as Nguyễn Thuyên). He is said to have composed a written invocation in Chữ Nôm to drive away crocodiles from the Lô River during the reign of Trần Nhân Tông (1279–1293). In the fourth year of Thiệu Bảo (1282), Emperor Trần Nhân Tông ordered Nguyễn Thuyên to perform a ritual and throw his invocation into the river, after which the crocodiles disappeared (as recorded in Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư). Unfortunately, his poem and many of his other works have been lost. Some surviving Chữ Nôm texts from the Trần dynasty include Buddhist verses by Emperor Trần Nhân Tông and Zen master Huyền Quang, such as Cư trần lạc đạo phú, Đá thú lâm tuyền thành đạo ca, and Vịnh Hoa Yên tự phú, which were compiled in Thiền tông bản hạnh (the earliest remaining printed edition dates to 1745).

From that time until the early 20th century, Chinese and Chữ Nôm coexisted in Vietnamese society, each serving distinct yet complementary roles. The historical functions of Chinese and Chữ Nôm in Vietnam can be broadly summarized as follows:

2. The Role of Chinese Characters

Throughout more than a thousand years of Northern domination, Chinese characters held a dominant position in Vietnam. According to historical records, from the 12th to the 9th century, a series of Vietnamese intellectuals used brushes to write records or literary compositions in Chinese characters. A prominent figure among them was Khương Công Phụ (8th century), a native of Ái Châu (Thanh Hóa), who traveled to China to take the imperial examination and ranked first with a rhapsody and an essay written in Chinese characters (as recorded in Complete Tang Literature, Vol. 446). However, the surviving Chinese character texts by Vietnamese scholars from this period are scarce, and the extant copies are mostly found abroad.

It is noteworthy that it was precisely during the period when the Vietnamese gained their independence and autonomy—while establishing their own government modeled after the Chinese feudal state—that Chinese characters began to be actively and widely used by the Vietnamese in various aspects of social life. The role and function of Chinese characters from that time onward are reflected as follows:

(1) First, in administration, Vietnamese feudal dynasties, from the Đinh dynasty (10th century) to the Nguyễn dynasty (20th century), consistently used Chinese characters in official documents at all levels of government. From imperial edicts, decrees, and conferment orders issued by the court to memorials, petitions, and applications submitted by lower officials and commoners, all were written in Chinese characters. Ordinary people, being mostly illiterate, had to rely on or hire educated individuals to draft their petitions. Only on rare occasions were there edicts or letters from the emperor (such as Emperor Quang Trung's letter to Nguyễn Thiếp and his annotations on petitions from northern scholars) or documents and memorials from the populace written purely in Nôm script. Notable administrative texts in Chinese characters include Quân trung từ mệnh tập by Nguyễn Trãi (written on behalf of Lê Lợi) and the Châu bản triều Nguyễn, a collection of more than 50,000 documents from the Gia Long era to the Bảo Đại era (currently preserved at the National Archives Center in Hanoi).

(2) Alongside administration were education and examinations, in which all classical Confucian texts and academic compositions were written in Chinese characters. The training of national talents through Confucianism was actively pursued starting from the Lý dynasty. In 1070, during the reign of Lý Thánh Tông (1054–1072), the Văn Miếu – Quốc Tử Giám was built in Thăng Long as a place for the crown prince to study Chinese literature. In 1075, under Lý Nhân Tông (1072–1128), Vietnam held its first Confucian examination to select talents. From then until 1919, when the final imperial examination (Hội Examination) was held in Huế, a total of 2,898 individuals passed the highest level of imperial examinations. These scholars formed the intellectual backbone that contributed to Vietnam’s classical literary tradition over the centuries.

(3) The written culture of Vietnam (including works on history, geography, literature, religion, and beliefs) was primarily built upon Chinese characters. The Đại Việt sử ký, completed in 1272 by historian Lê Văn Hưu during the reign of Trần Thánh Tông (1258–1278), was the first official historical record of Vietnam. Consisting of 30 volumes, it is now lost, but it served as the foundation for later, more extensive historical records in subsequent dynasties, such as Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (carved and printed in 1697 during the Lê dynasty), Đại Việt sử ký tiền biên (completed in 1800 under the Tây Sơn dynasty), and Khâm định Việt sử thông giám cương mục (finished in 1881 under Emperor Tự Đức of the Nguyễn dynasty). Similarly, legal codes such as the Hình thư of the Lý dynasty (1042) and the Quốc triều hình luật of the Trần dynasty (1244) were lost, but later famous legal codes such as Quốc triều hình luật (1489, under Emperor Lê Thánh Tông, also known as the Hồng Đức Code) and Hoàng triều luật lệ (1815, under the Nguyễn dynasty, also called the Gia Long Code) remain.

Numerous scholarly works documenting and describing the Vietnamese people and their land were written in Chinese characters by accomplished writers such as Lê Hữu Trác (1724–1791), Lê Quý Đôn (1726–1784), Ngô Thì Sĩ (1726–1780), and Ngô Thì Nhậm (1782–1840). Using Chinese characters, Vietnamese literati developed a literary tradition that encompassed various genres, particularly poetry and prose fiction. Almost every Confucian and Buddhist scholar in Vietnam composed poetry in Chinese characters. Notable among the prose works is Truyền kỳ mạn lục by Nguyễn Dữ (mid-16th century), a collection of 20 short stories based on Vietnamese society at the time; the historical novel Hoàng Lê nhất thống chí by the Ngô family literary group, which depicts the turbulent period of late 18th- and early 19th-century Vietnam; and several other Chinese-language novels and essays, particularly those of Phan Bội Châu (1867–1940).

Beyond Confucian scholars, Chinese characters also served as a crucial medium for the dissemination of Taoist and Buddhist scriptures in Vietnam. They became deeply integrated into temples, shrines, pagodas, and historical sites. Chinese calligraphy, with its solemn and majestic appearance, was well-suited for inscriptions on steles to commemorate virtues and honor ancestors, as well as for decorative couplets and plaques in both public and private spaces. Of course, within these cultural and religious environments, the Vietnamese also used the Nôm script.

3. The Role of Chữ Nôm

When Chữ Nôm was created and gradually perfected spontaneously by its users (who were also its creators), Chữ Hán had already had a long history of "residence" and had served Vietnamese society effectively in many aspects of spiritual life, particularly in administration and the training of national talents. This was not necessarily due to the prestige of Chữ Hán itself, but rather to the advantage of a Chinese civilization that had spread throughout the region in medieval times. Through Chữ Hán, the Vietnamese, like many other peoples, transitioned from passive to active adoption. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to assign Chữ Nôm the task of reclaiming roles that Chữ Hán had long held in a deserving manner. In Vietnamese history, there were a few kings who were interested in Chữ Nôm and wanted to use it in administrative transactions (such as Hồ Quý Ly and Nguyễn Huệ), as well as intellectuals who sought to reform the script by replacing Chữ Hán with Chữ Nôm (such as Nguyễn Trường Tộ in Tế cấp bát điều presented to Emperor Tự Đức). However, all these commendable ideas and experiments were fleeting and did not leave any significant marks on Chữ Nôm. In such contexts, how did Chữ Nôm demonstrate its capabilities to contribute alongside Chữ Hán in building Vietnam's classical civilization?

(1) First, there were areas where Chữ Hán proved weak, even powerless, and had to yield to Chữ Nôm to fulfill its role. At least three fields allowed Chữ Nôm to showcase its potential optimally:

(a) The Vietnamese, like many other peoples, had a rich and diverse oral cultural heritage long before writing existed. This included stories, songs, proverbs, idioms, and riddles passed down through generations. Clearly, in order to record, collect, and edit this oral cultural treasure in Vietnamese, nothing was more suitable and faithful than directly using Chữ Nôm (rather than translating it into Chữ Hán). In fact, numerous such collections were made in Chữ Nôm, such as Lý hạng ca dao, which contains 256 folk songs; Nam quốc phương ngôn tục ngữ bị lục, comprising 27 sections of folk songs, proverbs, and riddles; and Nam ca tân truyện, which records traditional songs from Huế. A series of classical tuồng and chèo plays such as Văn Duyên diễn hí, Trương Viên diễn ca, and Lưu Bình trò can also be mentioned here.

(b) Chữ Nôm, written in verse form, was the most suitable and effective way to popularize and disseminate knowledge in various fields. This includes historical narrative books such as Việt sử diễn âm (16th century), Thiên Nam minh giám (first half of the 17th century), Thiên Nam ngữ lục (second half of the 17th century), and Đại Nam quốc sử diễn ca (19th century). Although most of the population was illiterate in Chữ Hán and Chữ Nôm, they could listen to these poetic works being read aloud multiple times, committing them to memory even when they were thousands of verses long. The same applies to "diễn ca" or "diễn âm" works in fields such as law (Hoàng Việt luật lệ toát yếu diễn ca) and medicine (Chẩn đậu diễn ca).

(c) The prominent role of Chữ Nôm was expressed in literary creations. Although scholars of all times wrote poetry and prose in Chữ Hán, only with Chữ Nôm could the Vietnamese create immortal literary masterpieces. The oldest surviving Chữ Nôm poetry collection is Quốc âm thi tập by Nguyễn Trãi (1380–1442), followed by Bạch Vân am quốc ngữ thi by Nguyễn Bình Khiêm (1491–1585). Notably, while prose fiction in Chữ Hán existed, Chữ Nôm literature overwhelmingly took the form of verse. The most outstanding and accomplished genres were long narrative poems in lục bát and song thất lục bát. These forms reached their pinnacle in the late 18th and early 19th centuries with works recognized worldwide, such as Chinh phụ ngâm khúc by Đoàn Thị Điểm (1705–1748) and Truyện Kiều (Đoạn trường tân thanh) by Nguyễn Du (1766–1820). Other notable Chữ Nôm poets from the 13th to the early 20th century include Nguyễn Huy Tự, Nguyễn Gia Thiều, Phạm Thái, Hồ Xuân Hương, Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, Nguyễn Công Trứ, Nguyễn Khuyến, and Trần Tế Xương. Thanks to them, the Vietnamese language was refined by incorporating both Chữ Hán and folk cultural elements, forming a literature rich in clarity and expressive power.

(2) On the other hand, Chữ Nôm did not always "work independently" but often collaborated with Chữ Hán to create and preserve cultural works. This is evident in several cases:

(a) Not to mention cases where a few scattered Nôm characters might appear as needed in scholarly Chinese texts, in folk life, Nôm characters were almost always used alongside Chinese characters to record village activities, local regulations, geographical records, deity genealogies, family genealogies, bookkeeping, petitions, contracts, etc. Alongside Chinese characters, Nôm also appeared in couplets, horizontal plaques, stone steles, and bronze bells in communal houses, temples, and shrines. There was even a poetic genre highly favored by commoner Confucian scholars, called "hát nói" (a style in ca trù singing), in which purely Nôm lyrics in Vietnamese were often interspersed with a few Chinese-character phrases.

(b) Nôm characters were also effectively used in the transcription of texts and the dissemination of written culture. For example:

- The classical scriptures of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism in Chinese could be translated into Nôm in two ways: either by summarizing the main ideas and converting them into Nôm verse for easier dissemination (such as Luận ngữ thích nghĩa ca, a Nôm lục bát poetic rendition of the Analects in 20 chapters); or by directly translating each Chinese sentence into Nôm (such as Thi kinh giải âm, which translated the entire collection of over 300 poems in the Book of Songs into Nôm). Some texts from Western languages were also sometimes abridged and translated into Nôm prose, such as Các Thánh truyện (1646), edited by Jeronijimo Maijorica (a 12-volume work, with 11 volumes still extant, totaling 1,672 pages).

- Similarly, some Chinese prose works by Vietnamese authors were later transcribed into Nôm prose through direct sentence-by-sentence translation. A notable example is the "annotated version" traditionally attributed to Nguyễn Thế Nghi (late 16th to early 17th century) for Nguyễn Dữ's Truyền kỳ mạn lục (mid-16th century), as well as the Nôm translation found in Cổ Châu Phật bản hạnh ngữ lục (16th century), with an extant engraved copy still preserved at Dâu Pagoda.

- There was also a series of reference books in which Nôm was used to explain the meanings of Chinese characters, often compiled in verse. By using these books, people could simultaneously learn both Chinese and Nôm. Some notable works of this type include Chỉ nam ngọc âm giải nghĩa (14th and 17th centuries), Tam thiên tự giải âm by Ngô Thì Sĩ (18th century), Nhật dụng thường đàm by Phạm Đình Hổ (18th century), Tự học giải nghĩa ca from the reign of Tự Đức (19th century), and Đại Nam quốc ngữ by Nguyễn Văn San (19th century), etc.

4. Additional Remarks

It is important to note that both Chinese and Nôm characters in Vietnam, whether used independently or in combination, were shaped using the same traditional manual methods. The primary methods of inscription included: (a) Handwriting with a brush on paper, fabric, silk, or any writable surface; (b) Carving with knives or chisels onto hard materials like wood, stone, or bronze to create engraved texts (steles, bells, plaques, etc.); (c) Engraving reversed characters onto wooden blocks to create printing plates for mass reproduction on paper. Thanks to this traditional printing method, Vietnamese works in both Chinese and Nôm were widely replicated and disseminated, fostering the development of the Chinese-Nôm literary tradition from the medieval period onward. Even into the early 20th century, many publishers continued to engrave and reprint numerous Hán-Nôm works, which sold well in the contemporary book market.

Additionally, it should be emphasized that from the 11th century onward, when the Vietnamese actively used Chinese characters for their own purposes, they began pronouncing them according to the phonetics of late Tang and early Song China. Over time, this pronunciation gradually diverged from its original homeland, increasingly influenced by Vietnamese phonology. This became known as the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation. Through this adaptation, both the Chinese language and its script became highly familiar to the Vietnamese, diminishing any sense of it being a "foreign language." Consequently, the emergence of Nôm was never meant to replace Chinese characters but rather to complement them in serving the societal needs of the Vietnamese people, as previously discussed.

From the early 20th century onward, the Latinized Vietnamese script (commonly known as Quốc ngữ) gradually replaced the roles of both Chinese and Nôm in most of their social functions. However, given the deep historical foundation of Hán-Nôm literature, the role of these scripts in preserving and transmitting traditional culture will never fade. For the Vietnamese people today, both Chinese and Nôm characters remain a sacred bridge linking the past with the present and future, playing an enduring role in the cultural life of scholars and ordinary citizens alike.

References

Đào Duy Anh. Chữ Nôm – Nguồn gốc, cấu tạo, diễn biến. NXB Khoa học Xã hội, Hà Nội, 1975.

2. Nguyễn Tài Cẩn. Nguồn gốc và quá trình hình thành cách đọc Hán Việt. NXB Khoa học Xã hội, 1979.

3. Phan Huy Chú. Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí. Manuscript in Chinese characters, 49 volumes. Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies Library (A. 1551/1-8).

4. Trần Văn Giáp. Tìm hiểu kho sách Hán Nôm (Thư tịch chí Việt Nam). Volume I, NXB Văn hoá, Hà Nội, 1984; Volume II, NXB Khoa học Xã hội, Hà Nội, 1990.

5. Nguyễn Quang Hồng (ed.). Văn khắc Hán Nôm Việt Nam (Tuyển chọn và lược thuật). NXB Khoa học Xã hội, 1992.

6. Nguyễn Quang Hồng. “Di sản Hán Nôm nhìn từ góc độ của khoa học ngữ văn.” Tạp chí Hán Nôm, 1987, No. 2.

7. Trần Nghĩa, Francois Gros (eds.). Di sản Hán Nôm Việt Nam (Thư mục đề yếu). Three volumes. NXB Khoa học Xã hội, Hà Nội, 1993.

8. Ngô Đức Thọ (ed.). Các nhà khoa bảng Việt Nam (1075–1919). NXB Văn học, Hà Nội, 1993.

This article by Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng was originally presented at the conference commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Society for Chinese Character Culture in Japan, Tokyo, March 1999. It was published in Ngôn ngữ & Đời sống, 1999, No. 5 (43). The author has granted permission for its reproduction on the Digitizing Vietnam website.

A Chance Discovery at Dâu Pagoda

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a group of researchers from the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies paid a visit to Dâu Pagoda (also known by its Sino-Vietnamese names Diên Ứng Tự, Pháp Vân Tự, or Cổ Châu Tự) in Thuận Thành, Hà Bắc (today part of Bắc Ninh Province). The trip was part of a field investigation to collect textual materials in Hán and Nôm scripts from this famous ancient pagoda of the Kinh Bắc region.

At that time, in a side chamber to the right of the ancestral hall stood a storeroom packed with all kinds of household and farming tools—winnowing baskets, trays, bamboo sieves, water scoops, and so on. Quite by chance, the researchers noticed among the clutter several engraved woodblocks belonging to the work Cổ Châu Pháp Vân Phật bản hạnh ngữ lục 古珠法雲佛本行語錄. Remarkably, the entire set of woodblocks remained complete.

This work was already known to scholars, as a printed copy had been preserved at the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies under the reference number A.818, collected earlier by the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in Hanoi. Yet, what made the discovery particularly exciting was that alongside this known text, the researchers also found two other related woodblock sets: a vernacular Nôm verse work titled Cổ Châu Phật bản hạnh 古珠佛本行 and a Hán prose ritual text titled Hiến Cổ Châu Phật tổ nghi 献古珠佛祖儀. Notably, printed copies of these two works were absent from EFEO’s collection and had never been recorded in the holdings of the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies at that time.

Three Works, Three Genres, One Thematic Thread

The three works are closely connected in content. Both Cổ Châu Pháp Vân Phật bản hạnh ngữ lục and Cổ Châu Phật bản hạnh recount the legend of Lady A Man and the deities of the Tứ Pháp (Four Dharma Goddesses), praising their virtues and miracles. The Hiến Cổ Châu Phật tổ nghi, meanwhile, contains ritual texts—prayers and offerings—expressing reverence toward the Buddhas.

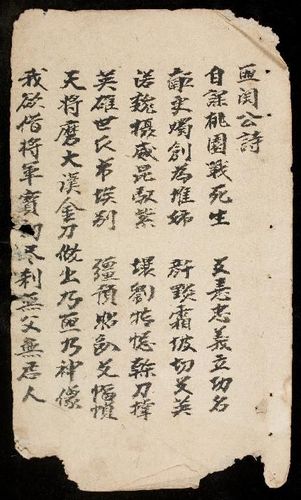

While the first two share the same narrative basis, they differ in form. The Cổ Châu Pháp Vân Phật bản hạnh ngữ lục is a bilingual Hán-Nôm prose text: the original Hán passages are followed by vernacular Nôm translations, engraved in smaller script. In contrast, Cổ Châu Phật bản hạnh is entirely written in Nôm using the popular lục bát (6–8 syllable) verse form, typical of oral Vietnamese tradition. The third, Hiến Cổ Châu Phật tổ nghi, is composed entirely in Classical Chinese prose. Within the pagoda, these were familiarly referred to as Cổ Châu lục, Cổ Châu hạnh, and Cổ Châu nghi, respectively.

Cổ Châu lục: A Unique Bilingual Text

The Hán text of Cổ Châu lục contains nearly 2,100 characters and is described as an ancient transmission of unknown authorship. Each phrase or sentence in Chinese is immediately followed by its Nôm translation, engraved at half-size—a “line-by-line translation” format characteristic of Lê–Trịnh period Hán-Nôm works. According to the colophon engraved on the blocks, the carving was completed in the autumn of the 13th year of the Cảnh Hưng era (1752, Lê dynasty). Based on textual and linguistic evidence, scholars infer that the Hán prototype may date back to the mid–late 14th century (late Trần dynasty).

The Nôm portion, totaling 2,360 characters, was rendered by a figure named Viên Thái (identity unknown). The script displays both phonetic loan characters and phono-semantic compounds, though pure phonetic loans dominate. Many words appear in archaic phonetic forms that were later replaced by phono-semantic ones—for example: ba (巴), tên (先), nay (尼).

The Nôm translation also preserves numerous archaic expressions and lexical items, such as “Hay chưng thầy thửa ở” (“to know where the master dwells”) and “Thực thời lỗi ấy chưng ai” (“Truly, whose fault was it?”), as well as ancient words like 谷 cóc ‘to know’, 沃 óc ‘to call’, 合 hợp ‘should’, and 羅𥒥 la-đá ‘stone’. Such features typify Nôm prose of the 16th–17th centuries. The word la-đá 羅𥒥, for instance, is only attested in texts predating the late 17th century, appearing no later than Alexandre de Rhodes’s Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum (1651). By Pigneau de Béhaine’s Latin–Vietnamese Dictionary (1773), only the monosyllabic đá remained.

These linguistic characteristics, together with the “line-by-line” translation format, suggest that the Nôm version of Cổ Châu lục likely dates from the late 16th to early 17th century.

Cổ Châu hạnh: A Lục-bát Nôm Poem

The Cổ Châu hạnh consists of 246 lục-bát verse pairs (about 3,450 characters). The author is unknown, but internal evidence offers clues to its dating. It references the Hồng Đức reign (1470–1497) of King Lê Thánh Tông and refers to China as “Đại Minh,” the Ming dynasty’s contemporary name (1368–1644). These clues suggest that the work was composed between 1470 and 1644, though this range is broad. Given linguistic parallels with Cổ Châu lục, it is plausible that Cổ Châu hạnh was composed contemporaneously or slightly later—again, around the late 16th to early 17th century.

Cổ Châu nghi: Ritual Texts for the Buddha

The Cổ Châu nghi comprises over 1,500 Chinese characters written in Classical prose. An inscription on its opening block states that the text was an old composition of uncertain date, newly engraved at Dâu Pagoda in the year Nhâm Tý (1792), the fifth year of Emperor Quang Trung’s reign under the Tây Sơn dynasty.

A Return from Oblivion

Although scholars had long been aware of the existence of old woodblocks at Dâu Pagoda, they remained unstudied and untouched until the Institute’s researchers rediscovered them in the late 1980s–early 1990s.

In 1995, the Cổ Châu woodblock trilogy and related texts were finally published in the volume Di văn chùa Dâu (Hán-Nôm Inscriptions of Dâu Pagoda), edited by Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng—marking the long-awaited return of these cultural treasures from centuries of obscurity.

(Adapted from “The Cổ Châu Woodblock Trilogy and the Hán-Nôm Heritage of Dâu Pagoda,” in Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng’s Ngôn ngữ. Văn tự. Ngữ văn [Language, Script, Literature]