1. The State Award for a Monograph on Nôm Script

On January 11, 2017, the President of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam signed Decision No. 104/QĐ-CTN awarding the Hồ Chí Minh Prize to 9 scientific and technological works, and Decision No. 105/QĐ-CTN awarding the State Prize to 7 scientific and technological works, according to the five-year review regulation. On January 15, 2017, at the Ministry of National Defense Auditorium in Hanoi, the Hồ Chí Minh Prize and State Prize for Science and Technology, Round 5, were presented to outstanding scientists from across the country. President Trần Đại Quang attended the ceremony and presented the awards to the winning scientists. In his speech at the ceremony, the President acknowledged: “The works awarded the Hồ Chí Minh Prize and State Prize for Science and Technology this time are excellent, representative works, effectively applied, and have great significance in protecting health, improving people's living standards, enhancing the competitiveness, position, and scientific and technological level of the country in the region and the world.”

During the ceremony, Mr. Chu Ngọc Anh, Minister of Science and Technology and Chairman of the State Prize Council, stated: “In the field of social sciences and humanities, there are outstanding achievements in the study of philosophy, history, and language, including clarifying the intellectual height of the Vietnamese people as well as the values, limitations, and valuable historical lessons left by our ancestors; there are studies on Nôm script according to a new theoretical framework and new approaches, which have been warmly received by the research community both domestically and internationally. These works are widely used in specialized studies of Nôm script and Hán Nôm literature in Vietnam and abroad today.”

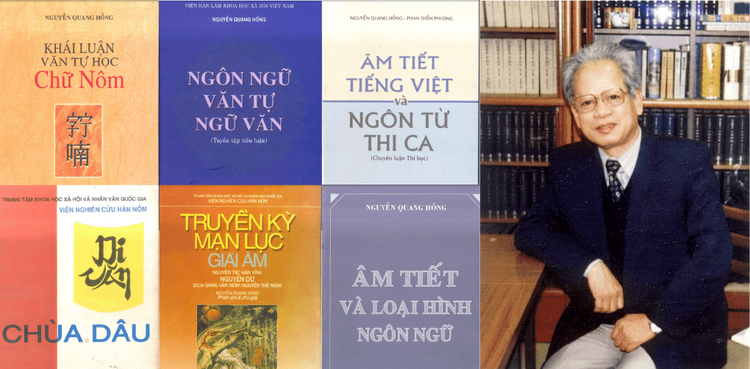

Among the works and authors honored in this round is the monograph Khái luận văn tự học chữ Nôm (An Introduction to chữ Nôm Grammatology) (Education Publishing House, 2008) by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng, former Deputy Director of the Institute of Hán Nôm Studies (Institute of Hán Nôm). This recognition at the national level is a well-deserved acknowledgment of a high-level theoretical work on philology by a leading scientist in the field of Hán Nôm and script studies. The Institute of Hán Nôm has had several former staff members awarded the Hồ Chí Minh Prize and the State Prize, but they had worked at the Institute for only a short time before moving to other units, receiving the award as staff members of those units. Therefore, this can be considered the first State Award granted to a scientist who has dedicated most of his career to the Institute of Hán Nôm Studies. In this sense, this prestigious award is an honor for the Institute of Hán Nôm and serves as motivation for its staff to continue contributing to the advancement of science and technology.

2. Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng: The "Powerful" Scholarly Figure

Although born (1939) and working in Vietnam, Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng had the fortunate opportunity to receive long-term training at foreign academic centers right from his student years. He graduated with a Bachelor's degree in Philology from Peking University (1965), earned his Associate Doctorate (now known as PhD) in Philology from Moscow State University and the Soviet Union's Institute of Oriental Studies (1974), and later obtained his Doctor of Science in Philology from Moscow State University (1985). With a solid foundation and the ability to absorb the finest knowledge from these two prestigious Eastern and Western literary scientific centers, he produced unique research works on Hán Nôm literature and linguistics. The overarching feature of his works is their high theoretical quality, logically and systematically developed research problems, and a writing style that is scientifically rigorous, yet often witty and engaging rather than overly rigid.

After many years of researching and teaching language and scripts at various universities and specialized research institutes, he has "unveiled" numerous key works: Văn khắc Hán Nôm Việt Nam (Han-Nôm Inscriptions in Vietnam, Editor, 1992), Âm tiết và loại hình ngôn ngữ (Syllables and Language Types, monograph, 1994, 2001, 2012), Di văn chùa Dâu (The Relics of Dâu Pagoda, Editor, 1996), Truyền kì mạn lục giải âm (An Interpretation of Truyền Kỳ Mạn Lục, Annotated, 2001), Tự điển chữ Nôm (Nôm Dictionary, Editor, 2006), Kho chữ Hán Nôm mã hoá (The Hán Nôm Encoded Collection, Co-editor, 2008), Khái luận văn tự học chữ Nôm (An Introduction to Nôm Philology, monograph, 2008), Tự điển chữ Nôm dẫn giải (Annotated Nôm Dictionary, 2 volumes, 2014, nearly 2,400 pages, a personal work), Âm tiết tiếng Việt và ngôn từ thi ca (Vietnamese Syllables and Poetic Language, written with his wife, Dr. Phan Diễm Phương, currently in press). He is also the author of more than 100 research articles published in specialized journals both domestically and internationally. He has been invited to give lectures and engage in scientific exchanges in the United States, France, Japan, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

3. An Introduction to chữ Nôm Grammatology: A "Robust" Scholarly Work

The fundamental and crucial feature of this monograph is its methodological premise, which centers on philology as the core concept. This is the key distinction of the book, as previous monographs on Nôm typically placed historical linguistics of the Vietnamese language above philology when approaching the treasure trove of Nôm script. By restoring the essence of philology to the approach of Nôm research, the book addresses a historical shortcoming in Nôm studies, which often focused too much on early-era texts while neglecting those from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Based on this methodological premise, the book develops its research systematically and with a strong theoretical foundation. While research on Hán Nôm often remains at a descriptive level, Nguyễn Quang Hồng's work, with its theoretical approach, aims to analyze and explain the events, which is a significant step forward compared to the usual approach, where one might simply think “anyone could know that!” However, synthesizing these scattered and isolated pieces of knowledge into a coherent theoretical system, as the author has done in his works (including this book), is not something just anyone can achieve.

Regarding content, the work systematically and comprehensively investigates the key issues in studying the traditional scripts of the Vietnamese people, with a primary focus on Nôm. The monograph is presented in six chapters and one appendix. The first three chapters introduce the traditional writing systems in Vietnam, explore the origins and development of the Nôm script, and identify its typological characteristics in comparison to Hán and other regional scripts. Chapters four and five delve into the functional and structural aspects of Nôm, tracing their evolution over time. The final chapter examines the social functions and operational environments of Nôm, alongside its role in relation to Hán and Quốc ngữ (the national script) in Vietnamese society, both past and present. Additionally, the appendix introduces the ideas of earlier scholars who aimed to create a Vietnamese script using brushstrokes resembling Nôm but functioning as a phonetic writing system, showcasing a unique aspect of ancient philological thinking.

The book is a significant achievement in research with both breadth and depth, presenting new insights grounded in a thorough accumulation and synthesis of knowledge. As a result, it quickly became a key teaching resource for the fields of Hán Nôm studies and literature in universities, graduate schools, and research institutions.

Therefore, the academic community was not surprised when the book was awarded the State Prize, and some even lamented that the work deserved a higher-level award. Scholars know that the author has long established his intellectual stature and academic influence, and the work has been recognized for its theoretical depth and framework-building capability.

4. Scholarly Companions

The academic community in Vietnam has acknowledged the leading positions of two giants in linguistics: Professor Cao Xuân Hạo (1930–2007) and Professor Nguyễn Tài Cẩn (1926–2011). When these distinguished scholars passed away, numerous commemorative articles were written about them, and two pieces titled Hoài niệm... (Recollections) by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng are among the most notable. These writings are both heartfelt and scientific, comprehensive yet detailed, clear and coherent, and appropriately critical in their scientific evaluation.

The success of these two Hoài niệm... articles, in addition to the writer’s solid knowledge and deep emotional connection with his colleagues, I believe, also lies in the shared approach to philological research between the three scholars. They were among the few who early on recognized the shortcomings of the Eurocentric mindset that was once quite prevalent in linguistic studies and research in general in Vietnam. Perhaps this is why, in his seminal work Phonology and Linearity (French edition, 1985), Professor Cao Xuân Hạo praised a 1974 work by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng with respectful words, aligning with his shared rejection of the European "segmentalist" approach, which criticized the use of European phonological theories that only applied to inflected languages when analyzing isolating and agglutinative languages of the East, such as Chinese, Vietnamese, and Japanese.

Reading these two Hoài niệm... articles, I found myself agreeing with two terms used by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng. He described two monographs on phonology and grammar by Professor Cao Xuân Hạo as "vạm vỡ" (robust), and he evaluated the monographs by Professor Nguyễn Tài Cẩn as "lực lưỡng" (vạm vỡ). Reflecting on this, although all three scholars had small, lean physiques, they were all "powerful" and "robust" in science. That is what is truly difficult to achieve. It seems to me that Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng's An Introduction to chữ Nôm Grammatology has also reached the "powerful" and "robust" level. Therefore, I would like to borrow these two terms to describe the person who used them so aptly. This State Prize is a confirmation of the value of the book and the stature of the scholar from the perspective of national science and technology management, after it had already been acknowledged by the academic community.

Footnotes:

This article was written by Associate Professor, Dr. Nguyễn Tuấn Cường, Director of the Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies, in 2017, when Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng was awarded the State Prize in Science and Technology for his work An Introduction to Nôm Philology. The article was published in Hán Nôm Journal, Issue 1 (140), 2017. We are reprinting the article here with the permission of the author, Associate Professor, Dr. Nguyễn Tuấn Cường.

(1). See three book review articles that were published: (1) Nguyễn Tuấn Cường, “Reading An Introduction to Nôm Philology by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng,” Hán Nôm Journal, Issue 4/2009, pp. 74-78. (2) Đinh Khắc Thuân, “Reading An Introduction to Nôm Philology,” Language and Life, Issue 5/2009, pp. 44-45. (3) Trần Đình Sử, “A New Contribution to Nôm Studies,” Literature and Arts, Issue 27 (2579), Saturday, 4/9/2009.

(2). See: (1) Nguyễn Quang Hồng, “Recollections of Cao Xuân Hạo,” Language and Life, Issue 11/2007, pp. 38-39 (electronic version: http://ngonngu.net/?m=print&p=354). (2) Nguyễn Quang Hồng, “Recollections of Professor Nguyễn Tài Cẩn,” Lexicography and Encyclopedia, Issue 2/2011, pp. 78-84 (electronic version: [http://khoavanhoc.edu.vn/tintuc sukien/878-gstskh-nguyn-quang-hng](http://khoavanhoc.edu.vn/tintuc sukien/878-gstskh-nguyn-quang-hng)).

(3). Cao Xuân Hạo, Phonology and Linearity: Thoughts on the Postulates of Contemporary Phonology, National University Publishing House, Hanoi, 2001, pp. 303-306.

Introduction

Among the 56 ethnic groups living within the territory of China, the Zhuang (壯) are the second largest (after the Han), numbering 15,555,820 people (according to the 1990 census). The Zhuang live mainly in Guangxi Province, with smaller numbers in Guizhou and Yunnan. This has also long been the traditional homeland of the group, which in origin is a branch of the ancient Baiyue peoples.

Within the Baiyue community, there were two major branches in its far southern region (stretching from Guangxi to Yunnan in China and northern to central Vietnam): the Tây Âu (Western Ou) and the Lạc Việt. Broadly speaking, the Zhuang—like the Tày and Nùng in Vietnam—are primarily related to the Tây Âu group, belonging to the Tai-Kadai language family; whereas the Mường and the Vietnamese (Kinh), originally belonging to the Austroasiatic family (Mon–Khmer branch), through a process of integration with Tày–Nùng groups and possibly also Austronesian peoples, came to form the Lạc Việt. Because of this close relationship in both origin and territory, the Vietnamese and Zhuang languages have likely preserved a number of corresponding linguistic elements, whether from genetic relations or from language contact.

Based on comparative analysis of materials written in Vietnamese chữ Nôm and Zhuang sawndip (square script), the traditional scripts of these two peoples, the author observes that the two languages share many morphemes that are similar in both sound and meaning. These may stem from a common Tai-Kadai origin, or may result from mutual borrowing through contact. The purpose of this paper is simply to present a list of such morphemes, providing reference material for related linguistic research.

In this list, corresponding morphemes between Vietnamese (V) and Zhuang (Z) will be presented with the following information:

Current orthography (in Latin script). Note that Zhuang uses final consonant letters to indicate tone, unlike Vietnamese Quốc ngữ, which uses diacritics. For technical reasons, the original traditional scripts (Vietnamese chữ Nôm and Zhuang sawndip) are not reproduced here, though they are recorded in the original sources and dictionaries.

Phonetic transcription in IPA. For Zhuang morphemes, transcription is based entirely on the Sawndip Dictionary. For Vietnamese morphemes, the transcription follows common conventions, but simplified: diacritics marking glides and diphthongs are omitted, and the medial [-ṷ-] is represented as [w]. Where vowel length contrasts exist, the “short” diacritic [ˇ] is used for Vietnamese and the length mark [:] for Zhuang. Tone is indicated with numbers (7 and 8 representing “checked tones”).

Basic shared meaning between the two languages (minor semantic differences are disregarded). The word idem is used to indicate that a morpheme has the same meaning as its Vietnamese counterpart. Dictionaries serve as the main source of glosses.

Example sentences, taken where possible from available dictionaries, with additional commentary as needed. In some cases examples may be omitted.

The notation <> is used to indicate correspondences and to separate examples from the two languages under comparison.Morphemes that are clearly borrowings from Chinese into both Vietnamese and Zhuang—though heavily assimilated—are not included in the list of common Viet–Zhuang morphemes examined here.

2. Comparative Linguistic Data1. (V) au [ău1]. Màu sắc (thương là đỏ) tươi thắm. Đôi má đỏ au <> (Z) aeuj [au3] . Màu tím. Va aeuj ‘hoa tím’.

2. (V) ba [ba1]. Trong ba ba: loài rùa ở nước ngọt, mai trơn. <> (Z) ba [pa1]. Idem.

3.(V) ban [ban1]. Một khoảng thời gian trong ngày. Ban trưa. Ban chiều. <> (Z) ban [pa:n1]. Idem. Ban ringz (ban trưa).

4. (V) bậc [bɤ̆k8 ].Tầng, nấc, ngôi thứ. Bậc thang. Bậc thềm. <> (Z) mbaek [bak7] : Idem. Aen lae neix miz caet mbaek ‘Vậy là có bảy bậc’.

5. (V) bầu [bɤ̆u2] / bù [bu2]. Trái bầu, vỏ trái bầu, vật hình trái bầu.<>(Z) mbaeuj [bau3] / byuz [pju-2]. Idem. mbaeuj laeuj ‘bầu rượu’.

6. (V) bầy [bɤ̆i2]. Đám đông động vật hoặc người. Lũ, nhóm. Bầy thú, bầy chim, bầy trẻ con. <> (Z) mbaiz [ba:i2]. Idem. mbaiz moz ‘một bầy bò’.

7. (V) bèo [bƐu2]. Loài thực vật sống nổi trên nước. Băm bèo, thái rau. Rẻ như bèo. <> (Z) biuz [pi:u2]. Idem. Rin cauh biuz mbouj sanq ‘ném đá khó bề khiến cho bèo tan’.

8. (V) bẻo [bƐu3]. Trong chà bẻo, chèo bẻo: Tên một loài chim, lông đen, đuôi dài, chẻ thành hai nhánh. <> (Z) beuj [pe:u3]. Trong ciq beuj: Idem.

9. (V) bỏ [bɔ3]. Đặt, để vật vào nơi nào đó. Tiền bỏ ống. <> (Z) box [po4]. Idem. Dawz gaeu box gang ‘bỏ gạo vào chum’.

10. (V) bóc [bɔkp7]. Lột bỏ lớp vỏ ngoài. Bóc lạc. Bóc ngắn cắn dài. <> (Z) bok [po:k7]. Cởi bỏ lớp bọc ngoài. Bok ndang ‘cởi áo’.

11. (V) bón [bɔn5]. Đút cho ăn dần từng tí một. Bón trẻ ăn. Bóm từng thìa cháo cho người ốm. <>(Z) bonj [po:n3]. Idem. bonj lungdik ‘bón trẻ ăn’.

12. (V) bọn [bɔn6]. Một nhóm người, một lũ người. Bọn trẻ. Bọn con buôn. <> (Z) mbongh [bo:ŋ6]. Một số đông người. mbongh mawz ‘lũ chúng mày’.

13. (V) bọt [bɔt6]. Bong bóng nước nhỏ li ti. Bọt bèo. <> (Z) foed [fot8]. Idem. Foed fauz ‘bong bóng nước’.

14. (V) bô [bo1]. Trong bô bô: Nói to, không giữ mồm giữ miệng. Bô bô cái mồm. <> (Z) boq [po5]. Idem. Gangj boq ‘nói phét, ba hoa’.

15. (V) bố [bo5]. Người cha. Con trai giống cha. <> (Z) boh [po6]. Idem. De dwg boh gou ‘Ông ấy là bố tôi’.

16. (V) bớt [bɤt7]. Làm cho ít đi, giảm thiểu. Bớt ăn bớt mặc. <> (Z) mbaet [bat7]. Idem. Mbaet gwn mbaet yungh ‘bớt ăn bớt tiêu’.

17. (V) bớt [bɤt7]. Vết sạm hiện rõ trên da. Trên cánh tay có cái bớt. <> (Z) mbad [ba:t8] Idem. Ga hưnj mbad ‘chân lên nhọt’.

18. (V) buôn [buon1]. Mua để bán lại lấy lãi. Làm nghề buôn bán. <> (Z) buenq [pu:n5]. Idem. Guh cangh buenq ‘buôn bán nhỏ, buôn vặt’.

19. (V) bừa [bɯa2]. Nông cụ kéo lê, làm cho đất phẳng và sạch cỏ. Con trâu đi bừa. <> (Z) bw [phɯ1]. Idem.

20. (V) bươn [bƜɤn1]. Đi vội. Lang bạt khắp nơi. Bươn chải. Bươn bả. <> (Z) banh [pa:n6]. Đi lung tung, lang bạt.

21. (V) bương [bɯɤŋ1]. Loài tre ống to và thẳng. Ống đựng bằng lóng cây này. Xách bương đi tưới rau. <> (Z) mbaengq [baŋ5]. Idem. mbaengq cuk ‘ống bương đựng cháo’.

22. (V) bứt [bƜt7]. Dùng tay làm cho đứt lìa. Bứt cỏ, bứt hoa. <> (Z) mbaet [bat7] / mbit [bit7]. Hái, ngắt. Mbaet byaek ‘hái rau’.

23. (V) cá [ka5]. Động vật có xương ở dưới nước, thở bằng mang. Cá chậu chim lồng. <> ca [ɕa1]. Idem.

24. (V) cái [kai5]. To, lớn, hàng đầu. Chiêc trống cái. Ngón chân cái. <> (Z) gaij [ka:i3]. Idem.

25. (V) cái [kai5]. Tiếng trỏ đơn vị vật thể. Cái thì đỏ, cái thì vàng, cái nào cũng đẹp. <> gaiq [ka:i5]. Idem. Gaiq neix ‘cái này’.

26. (V) cám [kam5]. Chất bột do lớp vỏ lụa hạt gạo vỡ vụn ra khi giã. Cho lợn ăn cám. <> (Z) raemz [ɣam2]. Idem. Miz raemz ndei ciengx mou ‘có cám để nuôi lợn’.

27. (V) cạo [kau6]. Dùng dao làm đứt sạch lông hoặc lớp vỏ ngoài. Đầu cạo trọc lóc. Cạo khoai. <> gauq [ka:u5]. Idem. Gauq cienj ‘dao cạo’.

28. (V) cày [kăi2]. Nông cụ có cán gỗ và lưỡi sắt, cắm và đẩy đi để lật xới đất. Cày sâu cuốc bẫm. Con trâu đi trước, cái cày đi sau. <> (Z) cae [ɕai1]. Idem. Fag cae ‘cái cày’ . Haet cae moux geij naz ‘một buổi sáng cày được hơn mẫu ruộng’.

29. (V) cằm [kăm2]. Phần dưới cùng của khuôn mặt. Tay chống cằm. <> (Z) giemz [ki:m2]. Idem. Giemz zhangz ‘cái cằm’.

30. (V) cặp [kăp8]. Thành đôi. Một cặp vợ chồng. <> gaep [kap7]. Kết thành một đôi. Dox gaep guh gvan baz ‘kết với nhau thành cặp vợ chồng’.

31. (V) cầm [kɤ̆m2]. Nắm, giữ trong tay. Hai tay cầm bốn trái dưa. <> (Z) gaem [kam1]. Idem. Dawz vaiz aeu gaem boek ‘giữ trâu phải cầm lấy dây chão’.

32. (V) chà [ca2]. Cành cây nhiều nhánh nhỏ, dùng để rào hoặc thả dưới nước cho cá đến ở. Thả chà (trà). <> (Z) cah [ɕa6]. Nhành cây gai. Rào giậu. Gunz bya miz cah lai ‘trên núi có nhiều cây gai’. Cah suen byaek ‘rào vườn rau’.

33. (V) chạc [cak8]. Dây bện. Xỏ chạc vào mũi trâu. <> (Z) cag [ɕa:k8]. Idem. Cag gyang ‘dây bện bằng xơ cọ’.

34. (V) chạm [cam6]. Khắc trổ trên đồ vật. Chạm tủ chè. <> (Z) camx [ɕa:m4]. Idem. Camx sigbei ‘chạm / khắc bia đá’.

35. (V) chang [caŋ1]. Sáng trưng, sáng chói. Chói chang. Nắng chang chang. <> (Z) cangj [ɕaŋ3]. Idem. Ndong cangj ‘sáng choang’.

36. (V) chão [cau4]. Dây bện loại to, bền. Dai như chão. <> (Z) caeuz [ɕau2]. Dây xỏ mũi trâu. Dawz vaiz aeu gaem caeuz ‘giữ trâu phải nắm lấy chão’.

37. (V) cháo [cau5]. Món ăn nấu loãng từ gạo hoặc bột. Cơm ráo cháo nhừ. <> caux [ɕa:u4]. Cơm (?). Gin caux ‘ăn cơm’.

38. (V) chạy [căi6]. Di chuyển nhanh bằng đôi chân. Sấm đằng đông vừa trông vừa chạy. <> (Z) caij [ɕa:i3]. Idem.

39. (V) chăng [căŋ1] / giăng [zaŋ1]. Vây bủa. Con nhện giăng tơ. <> (Z) cang [ɕa:ŋ1]. Idem. Bae dah cang bya ‘đi sông bủa (giăng) cá’.

40. (V) chặp [căp6]. Một chốc lát. Trời mưa một chặp rồi tạnh ngay. <> (Z) yaep [jap7]. Idem. Gou yaep ndeu menh bae ‘Tôi đợi một chốc rồi đi’.

41. (V) chậm [cɤ̆m6]. Không nhanh, tốc độ thấp. Trâu chậm uống nước đục. <> (Z) yaem [jam1]. Idem. Mwngz yaem yaem byaij ‘Anh đi từ từ nhé’.

42. (V) chật [cɤ̆t8]. Nhỏ hẹp, không đủ chỗ chứa. Phố chật người đông. <> (Z) caenz [ɕan2]. Chật chội, hẹp hòi. Sim caenz ‘bụng dạ hẹp hòi’.

43. (V) chen [cƐn1]. Lấn , lách giữa đám đông. Người đi quấn áo chen chân. <> (Z) caenx [ɕan4]. Idem. Caenz haeuj bae yawj ‘chen vào xem’. Ngoenz hauw vunz caenz lai ‘Ngày chợ phiên người chen chúc nhau’.

44. (V) chếch [cec7]. Lệch, không chính giữa. Nhìn chếch sang bên trái. <> (Z) caek [ɕak7]. Idem. Aen daiz neix cuengq caek loh ‘chiếc bàn này lệch rồi’.

45. (V) chênh [ceɲ1]. Không ngang bằng, không bằng phẳng. Hai đứa chênh nhau vài tuổi. Bàn kê chênh. <> (Z) ceng [ɕe:ŋ1]. Idem. Ceng ndaej gyae ‘chênh nhau khá xa’.

46. (V) chóc [cɔkp7]. Trong chim chóc. Chim chóc đầy rừng. <> (Z) roeg [ɣok8]. Idem. Duz roeg douh gwnz faex’chim đỗ trên cây’ / cok [ɕo:k7]. Chim sẻ. Roeg cok youq lai yiemh guh rongz ‘chim sẻ làm tổ dưới mái hiên’.

47. (V) chọc [cɔkp8]. Đâm. Đẩy mạnh vào đối tượng bằng vật thẳng và cứng. Chọc quả bưởi trên cây. Chọc tiết lợn. (Z) coeg [ɕok8]. Idem. Deng oen coeg haeuj fwngz ‘bị gai đâm vào tay’.

48. (V) chớ [cɤ5]. Đừng, không nên. Ai ơi chớ bỏ ruộng hoang. <> (Z) caej [ɕai3]. Idem. Caej luenh yungh cienz ‘chớ nên tiêu tiền bừa bãi’.

49. (V) chú [cu5]. Em trai của cha. Nó lú có chú nó khôn. <> (Z) cuj [ɕu3]. Idem.

50. (V) chuối [cuoi5]. Loài cây nhiệt đới, thân cây là các bẹ lá ôm nhau, cho quả thành buồng. <> (Z) gyoij [kjo:i3]. Idem.

51. (V) cong [kɔŋm1]. Dáng uốn vòng, không thẳng, không gấp khúc. Cành cây cong. <> (Z) goeng [koŋ5]. Idem. Rap naek hanz ci goeng ‘gánh nặng đến nỗi đòn gánh cong cả xuống’.

52. (V) còng [kɔŋm2]. Lưng khom, lưng gù. Bà Còng đi chợ. <> (Z) gungx [kuŋ4]. Idem. Hwet gungx ‘lưng còng, lưng gù’.

53. (V) cóng [kɔŋm5]. Tê cứng vì rét. Rét quá, cóng cả tay. <> (Z) gongj [ko:ŋ3]. Idem. Fwngz gongj ‘cóng cả tay’.

54. (V) cổ [ko3]. Phần cơ thể nối giữa đầu và mình. Hươu cao cổ. Một cổ hai tròng. <> (Z) goz [ku1]. Idem.

55. (V) cúi [kui5]. Đầu và cổ gục xuống. Cúi chào. Cúi mặt làm thinh. (V) goz [ku1]. Idem.

56. (V) của [kua3]. Đồ vật và tiền bạc thuộc sở hữu của ai đó. Của ăn của để. <> goz [ku6]. Idem. Trong guh gaiq ‘của cải, đồ đạc’.

57. (V) cuốc [kuok7]. Dụng cụ đào xới đất. Vác cuốc ra vườn cuốc đất. <> (Z) guek [ku:k7] / gvak [kwa:k7]. Idem. Dawz guek bae guek namh ‘Mang cuốc đi cuốc đất’.

58. (V) cụt [kut8]. Thiếu hụt, mất đi đoạn cuối. Chó cụt đuôi. Chim cánh cụt. <> (Z) gud [kut8]. Idem. Ma rieng gud ‘chó đuôi cụt’.

59. (V) cứ [kɯ5]. Vẫn giữ ý định hay hành động như cũ. Đừng sợ, cứ nói. Nó vẫn chứng nào tật ấy. <> (Z) gwq [kɯ5]. Idem. De gwq riu ‘nó vẫn cứ cười’.

60. (V) cứng [kɯŋ5]. Rắn chắc. Chân cứng đá mềm. <> (Z) geng [ke:ŋ1]. Idem. Bya dai ndang geng ‘cá chết thì thân nó cứng’.

61. (V) dài [zai2]. Có trường độ tương đối lớn. Dài lưng tốn vải. <> (Z) raez [ɣai2]. Idem. Diuz cag neix caen raez ‘sợ dây thừng này dài’.

62. (V) dặm [zăm6]. Quảng đường, bước đường. Dặm về còn xa. <> (Z) yamq [ja:m5]. Bước chân, bước đi. Song yamq roen ‘hai bước chân’. Yamq din ‘dấn bước’.

63. n(V) dâm [zɤ̆m1]. Màu đen. Chỉn thấy cái hạc dâm bay liệng. <> (Z) ndaem [dam1]. Idem. Naij ndaem lumj dukrek ‘mặt đen như giẻ lót nồi’.

64. (V) dần [zɤ̆n2]. Đồ đan bằng nan tre, có lỗ nhỏ, dùng làm sạch gạo sau khi xay lúa. Nomg nia thúng mủng dần sàng. <> (Z) ranz [ɣan2]. Idem. Ndaw ranz rang mbouj lad ‘Trong nhà dần sàng đều chẳng có’.

65. (V) dâng [zɤ̆ŋ1]. Đưa lên cúng, tặng một cách cung kính. Làm lễ dâng hương. <> (Z) daengj [taŋ3]. Idem. Daengj cogoeng ‘dâng cúng tổ tiên’.

66. (V) dè [zɛ2]. Tự hạn chế, tằn tiện trong khi dùng. Ăm tiêu dè sẻn. <> (Z) ce [ɕe1]. Idem. Ciem ce ‘kiệm dè’.

67. (V) dẹp [zɛp8]. Thu gọn vào một chỗ hoặc bỏ đi. Dọn dẹp nhà cửa. <> (Z) caeb [ɕap8]. Idem. caeb conz doxgaiq ‘dọn dẹp đồ đac’.

68. (V) diều [zieu]. Diều hâu, loài chim to, thường bắt gà con ăn thịt. <> (Z) yiuh [ji:u6]. Idem.

69. (V) dỏ [zɔ3]. Trong dòm dỏ: dòm ngó vẻ dò xét. Dòm dỏ nhà người ta. <> (Z) yoj [jo3]. Dò xem. Gou bae yoj gaeuj ‘tôi đi ngó xem’.

70. (V) dòm [zɔm2]. Nhìn qua chỗ hở, vẻ dò xét. <> Bình dưa lọ muối chắt chiu nom dòm. <> (Z) ndomq [do:m5]. Idem.

71. (V) dọn [zɔn6]. Thu xếp, gom dồn lại. Thu dọn đồ đạc. Dọn dẹp nhà cửa. <> (Z) conz [ɕon2]. Idem. Ndaw ranz aeu caeb conz ‘Dọn đồ đạc trong nhà lại’. Dawz gij bwnh conz ndei Thu dọn chỗ phân bón kia lại’.

73. (V) dựng [zɯŋ6]. Đặt vật chiều thẳng đứng. Dựng cột nhà. <> (Z) daengj [taŋ3]. Dawz faex daengj hwnjdaeuj ‘Dựng khúc gỗ này lên’.

74. (V) đàng [daŋ2] / đường [dɯɤŋ2]. Lối đi lại. Đi một ngày đàng, học một sàng khôn. <> (Z) dangz [ th a:ŋ2]. Idem.

75. (V) đào [dau2]. Dùng dụng cụ moi đất lên. Đào củ mài. <> (Z) daeuq [tau5]. Idem. Daeuq duh namh ‘đào củ lạc’.

76. (V) đạp [dap8]. Giẫm chân lên. Chân đạp lên sỏi đá. <> (Z) dab [ta:p8]. Idem. Din dab hwnj daengq ‘chân đạp lên ghế’.

77. (V) đằn [dăn2]. Dùng sức hoặc vật nặng đè xuống. Khúc gỗ đằn lên chân. <> (Z) daenz [tan2]. Idem. Aeu rinbya daeuj daenz ‘Lấy đá đằn lên’.

78. (V) đâm [dɤ̆m1]. Va chạm mạnh, húc vào. Hai con trâu đâm nhau. <> (Z) daemj [tam3]. Idem. Vaiz dox daemj ‘trâu húc nhau’ / daem [tam1]. Va phải Haet dox daemj , haemh dox dengj ‘sáng va tối đụng’.

79. (V) đâm [dɤ̆m1]. Chích vào, thọc vào. Kim đâm vào tay. <> (Z) ndaemq [dam5]. Idem. Gaj mou ciuq hoz ndaemq ‘đâm thẳng vào cổ họng con lợn’.

80. (V) địu [diu6]. Dùng túi mang theo. Địu con lên rẫy. <> (Z) diuj [thi:u3]. Mang theo. Mungz diuj daeh ‘Tay mang túi vải’.

81. (V) đọi [dɔi6]. Chén, bát ăn cơm. Miếng khi đói bằng đọi khi no. <> (Z) duix [tu:i4]. Idem.

82. (V) đọt [dɔt8]. Ngọn, búp lá. Đọt chuối.<> (Z) dug [tuk8]. Idem. Song ~ byaek ‘hai đọt rau’.

83. (V) đồ [do2]. Vật dụng. Đồ đạc trong nhà. <> (Z) dox [to4]. Idem. Trong doxgaiq ‘đồ đạc’.

84. (V) đỗ [do4] / đậu [dɤ̆u6]. Dừng, nghỉ lại. Chim đỗ trên cành. <> (Z) duh [tu6] / douh [tou6]. Idem. Duzroeg duh gwnz faex ‘chim đỗ trên cành’.

85. (V) đồi [doi2]. Nơi đất đá nổi cao. Ngọn đồi trọc. <> (Z) ndoi [do:i1]. Idem. Soengq gvaq ndoi gvaq ndoeng, de song boux nanz liz ‘Tiễn nhau qua đồi lại qua rừng, hai người vẫn khó lòng chia tay’.

86. (V) đốn [don5] / đẵn [dan4]. Chặt cây, ngã gỗ. Đốn cây. Chém tren đẵn gỗ trên ngàn. <> (Z) donj [to:n3]. Chặt khúc. Go faex donj geij geh ‘một cây chặt thành mấy khúc’.

87. (V) đồng [doŋ2]. Vùng đất cày cấy, trồng trọt. Cày đồng đang buổi ban trưa. <> (Z) doengh [toŋ6]. Idem.

88. (V) đứt [dɯt7]. Lìa ra, rời ra. Nòng nọc đứt đuôi. <> (Z) daek [tak7]. Idem.

89. (V) éo [ɛu5]. Màu xanh sáng. Xanh éo. <> (Z) heu [he:u1]. Idem. Byaek heu ‘bắp cải xanh’.

90. (V) ếch [ec7]. Sinh vật cùng loài với nhái mà to hơn, ở ao hồ. Ếch ngồi đáy giếng. <> (Z) aek [ak7]. Idem.

91. (V) gà [ɣa2]. Loài gia cầm, con trống gáy về sáng. Con gà cục tác lá chanh.<> (Z) gaeq [kai5]. Idem. ~ boux ‘gà trống’.

92. (V) gác [ɣak7]. Trong gốc gác: nguồn gốc, lai lịch. Gốc gác nhà ta ở Hà Tĩnh. <> (Z) rag [ɣa:k8]. Phần rễ của cây. Rag faex ‘rễ cây’.

93. (V) gái [ɣai5]. Người thuộc giới nữ. Sinh được một gái một trai. <> (Z) gaij [kha:i3]. Idem.

94. (V) gạo [ɣau6]. Nhân hạt lúa, chứa tinh bột. Thóc cao gạo kém. <> (Z) gaeuj [khau3]. Idem. Gaeuj nu ‘gạo nếp’.

96. (V) gạo [ɣau6]. Cây cùng họ với cây gòn, cao to, hoa đỏ, quả có xơ bông. Đầu làng có cây gạo. <> (Z) reux [ɣe:u4]. Idem. Maex reux ‘cây gạo’. Va reux ‘hoa gạo’.

97. (V) gàu [ɣău2]. Chất cáu bẩn từ da đầu. Đầu có nhiều gàu. <> (Z) raeu [ɣau1]. Idem. Gwnz gyaeuj miz raeu ‘trên đầu có gàu’.

98. (V) gằm [ɣăm2]. Cúi mặt yên lặng. Xấu hổ, cúi gằm mặt xuống. <> (Z) gaemz [kam2]. Idem. gaemz gyaeuj ‘cúi đầu’.

99. (V) gắp [ɣăp7]. Dùng kẹp hay đũa cặp lấy vật gì. Gắp lửa bỏ tay người. <> (Z) gip [kip7]. Gắp, nhặt. Gip haex vaiz ‘gắp/nhặt phân trâu’.

100. (V) gặp [ɣăp8]. Cùng thấy mặt nhau tại một nơi. Người đâu gặp gỡ làm chi. <> (Z) roeb [ɣop8]. Idem. Roeb sou youq Namningz ‘gặp các ông ở Nam Ninh’.

101. (V) gắt [ɣăt7]. Nồng đậm quá mức, gây cảm giác khó chịu. Nước mắm mặn gắt. <> (Z) gaet [kat7] / get [ke:t7]. Idem. Gij laeuj neix gaet lai ‘rượu này gắt quá’.

102. (V) gật [ɣɤ̆t8]. Gục đầu ngẩng lên, tỏ ý tán đồng. Anh ấy gật một cái là xong ngay. Ông ta gật gù tán thưởng. <> (Z) ngaek [ŋak7]. Trong ngaek gyaeuj ‘gật gù’.

103. (V) gâu [ɣɤ̆u1]. Tiếng chó sủa. Chó sủa gâu gâu. <> (Z) raeuq [ɣau5]. Idem. Ma raeuq ‘chó gâu’.

104. (V) ghé [ɣɛ5]. Liếc mắt nhìn xéo. Ghé mắt trông lên thấy bảng treo. <> (Z) rez [ɣe2]. Idem. Lwgda rez gvaqbae ‘ghé mắt nhìn’.

105. (V) giàm [zam2]. Lồng chim. Nào ai đan giậm giật giàm bỗng dưng. <> (Z) camj [ɕa:m3]. Lồng gà bằng tre. Aeu camj daeuj camj gaeq ‘mang lồng tới nhốt gà’.

106. (V) giạm / dạm [zam6]. Ướm hỏi trước. Giạm vợ cho con . <> (Z) cam [ɕa:m1]. Xin hỏi. cam nuengx bae gizlawz ‘xin hỏi cô nàng đi đâu vậy’.

107. (V) giàn [zan2]. Mặt bằng được kê dựng lên cao. Giàn mướp. <> (Z) canz [ɕa:n2]. Dak haeux youq gwnz canz ‘trên giàn đang phơi thóc’.

108. (V) giày [zăi2]. Đồ dùng có đề mang kín bàn chân. Giày da Nam Định. <> (Z) yaiz [ja:i2]. Idem. yaiz baengz ‘giày vải’.

109. (V) giặm [zăm6]. Trồng tỉa xen vào chỗ trống. Giặm mạ vào ruộng. <> (Z) semz [θe:m2] / comj [ɕo:m3]. Idem. semz gyaj ‘giặm mạ’. Gumz lawz noix cix comj ‘mảnh đất còn trống kia cần phải cấy giặm mạ vào’.

110. (V) giắt [zăt7]. Nước đái tháo dây dưa từng tí một. Đái giắt. <> (Z) yaet [jat7]. Idem. Nyouh yaet ‘đái giắt’.

111. (V) giặt [zăt8]. Giũ quần áo với nước cho sạch. Nước trong, ta giặt yếm.<> (Z) saeg [θak8]. Idem. Bae haenz dah saeg buh ‘ra sông giặt áo’.

112. (V) giấm [zɤ̆m5] / rấm [ʐɤ̆m5]. Giữ, giấu kín, ủ kín. Giấm xoài cho chín. Giấm giúi trao cho nhau. <> (Z) yaem [jam1] / yaemh [jam6]. Ngầm, lén. Aeu lwgda dox yaem ‘đưa mắt ngầm mách bảo nhau’. Gou yaemh yaemh daengz henz mwngz ‘Tớ len lén đến sát bên cạnh’.

113. (V) giậm / dậm [zɤ̆m6]. Nện bàn chân xuống đất. Giậm chân kêu tời. <> (Z) caemq [ɕam5] / daemh [tam6]. Idem. Caemq din ‘giậm chân’. Lwg nyez fat heiq caemq caemq daenh daenh ‘thằng bé bực tức liên tục giậm chân’.

114. (V) giậm [zɤ̆m6]. Đồ đan bằng tre để bắt cá. Đánh giậm. Nào ai đan giậm giật giàm. <> (Z) yaemz [jam2]. Vó đánh cá. Aeu saeng bae yaemz bya ‘mang vó đi đánh bắt cá’.

115. (V) giấu [zɤ̆u5]. Cất giữ kín. Giấu kín mọi chuyện. <> (Z) caeu [ɕau1] / yaeuj [jau3]. Cất giữ. Yaeuj ceh fag guh faen ‘cất giữ những hạt thóc chắc mẩy để làm giống’.

116. (V) giun [zun1]. Loài trùng có đốt, sống chui dưới đất. Con giun xéo lắm cũng quằn. <> (Z) nduen [du:n1] / ndwen [dɯ:n1]. Idem. Dwk ndwen coq bit ‘Đào giun cho vịt ăn’.

117. (V) giương [zɯɤŋ1]. Mở rộng, căng ra, nâng cao. Giương buồm ra khơi. Giương đôi mắt ếch. <> (Z) caengz [ɕaŋ2]. Idem. Caengz da dwk yawj ‘Giương mắt nhìn’.

118. (V) gõ [ɣɔ4]. Đập nhẹ vào vật cứng, nghe thành từng tiếng. Tụng kinh gõ mõ. Nghe lạch cạch có tiếng gõ cửa. <> (Z) roq [ɣo2]. Idem. roq dou ‘gõ cửa’. roq gyong ‘gõ trống’.

119. (V) gom [ɣɔm1]. Dồn lại, tích góp lại. Thu gom tiền để mua trâu. <> (Z) rom [ɣo:m1]. Rom cienz caep ranz moq ‘gom tiền làm nhà mới’.

120. (V) gốc [ɣokp7]. Phần dưới cùng của thân cây. Vốn có ban đầu. ThằngCuội ngồi gốc cây đa. Trả nợ cả gốc lẫn lãi.<> (Z) goek [kok7]. Idem. Goek raemx ‘nguồn nước’. Saw goek ‘chữ cổ’. Miz goek cij miz lei ‘có gốc mới có lãi’.

121. (V) gối [ɣoi5]. Trong đầu gối. Mặt trước nơi ống chân khớp với đùi. Đói đầu gối phải bò. <> (Z) gaeuh [kau6]. Trong Duzgaeuh ‘đầu gối’.

122. (V) há [ha5]. Mở to miệng. Há miệng mắc quai. Há miệng chờ sung <> (Z) aj [a3]. Idem. Aj bak dwk hunghung ‘miệng há cực to’.

123. (V) han [han1]. Hỏi, hỏi han. Trước xe đon đả han chào. <> (Z) han [ha:n1]. Trả lời . De cam bae cam dauq cungj mbouj han ‘hỏi tới hỏi lui mãi mà nó cũng không trả lời’.

124. (V) háng [haŋ5]. Phần cuối của thân người, giữa hai đùi. Đứng giạng háng. <> (Z) hangx [ha:ŋ4]. Idem.

125. (V) hao [hau1]. Hao hao: vẻ giống nahu. Chị em nó hao hao giống nhau. <> (Z) haeuj [hau3]. Idem. Naj de haeuj daxboh ‘nó hao hao giống bố’.

126. (V) hằm [hăm2]. Hằm hằm; vẻ mặt tức giận. <> (Z) haemz [ham2]. Idem. Ho haemz ‘căm tức’.

127. V) hằn [hăn2]. Nổi vết. Vết tấy. Trán hằn nhiều vết nhăn. <> (Z) haenz [han2]. Idem.

128. (V) hếu [heu5]. Màu trắng bệch. Cái gáy trắng hếu. Hàm răng trắng hếu <> (Z) hau [ha:u1]. Màu trắng.

129. (V) hoẵng [hwaŋ4]. Thú rừng, giống nai, lông vàng. gvangh [kwa:ŋ6]. Idem.

130. (V) hong [hɔŋm1]. Hơ đồ vật bên lửa cho khô. Hong quần áo bên bếp lửa.<> (Z) hangq [ha:ŋ5]. Idem. Bya cuengq gwnz feiz hangq ‘hong cá trên lửa’.

131. (V) hong [hɔŋm6]. Khoang trống trong cổ, nơi tiếp giáp với miệng và thực quản. Nói rát cả cổ họng. <> (Z) hongh [ho:ŋ6]. Idem.

132. (V) hôm [hom1]. Buổi tối. Ăm bữa hôm, lo bữa mai. <> (Z) haemh [ham6]. Idem. Haemh gonq ‘đêm hôm trước’.

133. (V) kẽ [kɛ4]. Chỗ hở hẹp. Nhìn qua kẽ hở. Kẽ răng. <> (Z) geh [ke6]. Idem. Geh dou ‘khe cửa’.

134. (V) kén [kɛn4]. Chọn lựa. Kén cá chọn canh. <> (Z) genj [ke:n3]. Idem. Genj haeux ceh ‘chọn giống lúa’.

135. (V) kéo [kɛu5]. Đồ dùng để cắt, gồm hai thanh ghép với một trục quay. Dùng kéo cắt vải. <> (Z) geuz [ke:u2]. Idem.

136. (V) kéo [kɛu5]. Lôi đi. Cùng nối nhau đi theo hàng dài. Trâu kéo cày. Đàn kiến kéo nhau đi. <> (Z) geuj [ke:u5]. Idem. Hoenz geuj hwnj mbwn ‘khói cuốn lên trời’.

137. (V) kẹp [kɛp6]. Cắp, ép chặt vật vào giữa. Càng cua kẹp tay. <> (Z) geb [ke:p8]. Idem.

138. (V) kham [xam1]. Kham khổ: khổ cực, nghèo nàn. Ăn uống kham khổ. Đời sống kham khổ. <> (Z) gaemz [kham2]. Đắng. Mbei doek cauq lawz cauq lawz gaemz ‘mật rơi vào nồi nào thì nồi ấy đắng’ / goem [khom2]. Idem. Lwg goem ‘mướp đắng’ / gum [khum1]. Idem. / haemz [ham2]. Đắng . Gian nan. ~ baenz mbei ‘đắng như mật’ Gwn ~ gwn hoj ‘ngậm đắng nuốt cay’.

139. (V) khẳng [xăŋ3]. Khẳng khiu: gầy khô. Chân tay khẳng khiu. Cành cây khẳng khiu. <> (Z) gaengz [kaŋ2]. Gầy yếu.

140. (V) kiệt [kiet8]. Keo kiệt: hà tiện, bủn xỉn. Lão già keo kiệt. <> (Z) ged [ke:t8]. Idem. Mwngz ndaej ged baenzlai? ‘keo kiệt đến thế sao?’.

141. (V) là [la2]. Tiếng chỉ báo đối tượng được giải thích. Em là con gái nhà quê. <> (Z) laz [la2]. Idem.

142. (V) lăm [lăm1]. Cà lăm: nói lắp. Nó mắc tật nói cà lăm. <> (Z) laemh [lam6]. Idem. Vunzlaux gangj haengj laemh ‘ông lão nói cứ hay lặp đi lặp lại’.

143. (V) lăn [lăn1]. Quay tròn chuyển đi trên một bề mặt. Cho gỗ lăn xuống chân đồi. <> (Z) laen [lan2]. Xe cuộn lại. Aeu biz ma laen cag ‘Lấy cỏ râu rồng xe dây thừng’.

144. (V) lấn [lɤ̆n5]. Chen đẩy, vượt sang. Quân giặc xâm lấn bờ cõi. <> (Z) laenz [lan2]. Idem. laenz gvaq maz ‘lấn sang’.

145. (V) lọc [lɔkp8]. Lừa lọc: lừa dối, lường gạt. <> (Z) luk [luk7] / lok [lo:k7]. Idem. Mwngz gaej luk gou ‘mày chớ có lừa tao’.

146. (V) lòi [lɔi2]. Lợn lòi: lợn rừng. <> (Z) laih [la:i6]. Idem.

147. (V) lột [lot8]. Bóc, tách, trút bỏ lớp ngoài. Rắn lột xác. <> (Z) lot [lo:t7]. Bong da, trầy da.

148. (V) lợm [lɤm6]. Cảm giác buồn nôn. Lợm giọng buồn nôn. <> (Z) laemz [lam2]. Idem. Muz laemz: ‘buồn nôn’.

149. (V) lu [lu1]. Chum to đựng nước. <> (Z) luh [lu6]. Idem.

150. (V) luồn [luon2]. Chui qua lỗ hổng. Xe chỉ luồn kim. <> (Z) luen [lu:n1]. Idem. Duz ma luen congh ciengz ‘chó chui qua lỗ chân tường’.

151. (V) lưa [lɯa1]. Thừa ra, sót lại. Kẻ mất người lưa. <> (Z) lw [lɯ1]. Idem. Noh lw dwk baenz raeuh ‘còn lại khá nhiều thịt’.

152. (V) lưỡi [lɯɤi4]. Bộ phận mềm trong miệng, dể nếm thức ăn. Uốn ba tấc lưỡi. <> (Z) linx [lin4]. Idem.

153. (V) má [ma5]. Chó má:loài chó. <> (Z) ma [ma1]. Chó. Duz ma luen congh ciengz ‘Chó chui qua lỗ chân tường’.

154. (V) má [ma5]. Lúa má: trỏ lúa đang trồng. Ngoài đồng lúa má tốt tươi. <> (Z) max [ma4]. Lúa nương.

155. (V) mái [mai5]. Trỏ giống cái loài chim. Gà mái ấp trứng. <> (Z) maih [ma:i6]. Trỏ bộ phận sinh dục giống cái.

156. (V) mảnh [mɛɲ3]. Mẩu vỡ từ vật cứng. Mảnh chĩnh vứt ngoài bụi tre. <> (Z) meng [me:ŋ1]. Idem.

156. (V) mào [mau2]. Chốc mào: loài chim có chùm lông dựng cao trên đầu. <> (Z) mauh [ma:u6]. Roegmauh: ‘chốc mào’.

157. (V) mày [măi2]. Nhân xưng ngôi 2 số ít. <> (Z) mawz [maɯ2]. Idem.

158. (V) mận [mɤ̆n6]. Loài cây họ đào, hoa trắng, quả chua. Bây giờ Mận mới hỏi Đào. <> (Z) maenj [man3]. Idem. Mak maenj mbouj cug gwn cix soemj ‘Quả mận chưa chín ăn sẽ chua’.

159. (V) mất [mɤ̆t5]. Không còn, hết, chết. Tiền mất tật mang. <> (Z) maet [mat7]. Idem.

160. (V) mẹ [mɛ6]. Người đàn bà sinh ra con. Một lòng thờ mẹ kính cha. <> (Z) meh [me6]. Idem. Lwg gaej lumz meh ciengx ‘Làm con chớ quên ơn mẹ sinh thành’.

161. (V) mệt [met8]. Nhọc, mỏi, kiệt sức. Làm lụng không biết mệt. <> (Z) mieg [mi:k8]. Idem. Gij rengz gou mieg liux ‘Tôi đã mệt mỏi lắm rồi’.

162. (V) mịn [min6]. Bột nhỏ hạt, sờ thấy mướt tay. Khoai mịn. Mịn màng. <> (Z) mienz [mi:n2]. Idem. Gij mba haeux neix mienz lai ‘Chỗ bột gạo ấy thật là mịn’.

163. (V) mịt [mit8]. Nom không rõ, lu mờ. Mờ mịt, mịt mùng. <> (Z) myad [mja:t8]. Idem. Haemh neix ndaundeiq müo myad myad ‘Đêm nay sao trời mờ mịt’.

164. (V) móc [mɔkp7]. Sương nặng hạt. Mưa móc tưới nhuần. <> (Z) mok [mo:k7]. Idem. Haet neix mbwn laep mok ‘Hôm nay sương mù dày đặc’.

165. (V) mọt [mɔt8]. Loài trùng nhỏ đục gỗ. Con mọt sách. <> (Z) mod [mo:t8]. Idem. Mod dwk sim faex ‘Mọt đục sâu vào thân cây’.

166. (V) mối [moi5] / mai [mai1]. Sợi chỉ, dây nối. Nhện chờ mối ai. Ông mai bà mối. <> (Z) mae [mai1]. Idem. mae goenq caiq swnj ‘Sợi đứt thì nối lại’.

167. (V) mới [mɤi5]. Trái với cũ. Dọn sang nhà mới. <> (Z) mawq [maɯ5] / moq [mo5]. Idem. Guh ranz moq ‘Dựng nhà mới’.

168. (V) mừng [mɯŋ2]. Vui sướng đón nhận điều tốt lành. Tay bắt mặt mừng. Mừng anh chị tốt đôi <> (Z) maengx [maŋ4]. Idem. Lwgngez daenj buh moq gig maengx ‘Thằng bé được mặc áo mới mừng lắm’.

169. (V) mương [mɯɤŋ1]. Ngòi dẫn nước vào ruộng. <> (Z) mieng [mi:ŋ1]. Idem. Hai mieng bae coh naz ‘Khơi mương dẫn nước vào ruộng’.

170. (V) nài [nai2]. Van xin, năn nỉ. Vật nài van xin. <> (Z) naih [na:i6]. Idem.

171. (V) nào [nau2]. Tiếng tỏ ý thúc giục. Nào ta đi thôi nào. <> (Z) nauh [na:u6]. Idem.

172. (V) này [năi2]. Đây. Này là em ruột, này là em dâu <> (Z) neix [nei4]. Idem. Gij mak neix ndei gwn ‘Những quả này ăn ngon’.

173. (V) nẫu [nɤ̆u4]. Chín nục, chín ngấu, ruỗng nát. Trái chín nấu. Buồn nẫu ruột. <> (Z) naeuh [nau6]. Ruỗng nát. Vaiz dai gok mbouj maeuh ‘Trâu chết, sừng không ruỗng nát’.

174. (V) nén [nɛn5]. Đè xuống, giằn xuống, ép chặt. Nắm cơm nén chặt. Nén lòng chờ đợi. <> (Z) naenx [nan4]. Idem. Naenx gyaq ‘ép giá’ . Maenx heiq ‘giằn lòng’.

175. (V) nga [ŋa1]. Tục tằn, ngây ngô, ngớ ngẩn. Phàm gian óc chớ nga chơi. <> (Z) ngah [ŋa6]. Đần độn. Gaenz ngah ‘người ngây’.

176. (V) ngái [ŋai5]. Xa ngái: xa xôi. <> (Z) gyae [kjai1]. Xa. Byaij roen gyae ‘đi đường xa’.

177. (V) ngại [ŋai6]. E dè, không hào hứng. Đường xa chớ ngại Ngô, Lào. <> (Z) aix [a:i4]. Idem.

178. (V) ngang [ŋaŋ1]. Lưng chừng ở giữa. Mây bay ngang đèo. Ngang lưng thì thắt bao vàng. <> (Z) gyang [kja:ŋ1]. Idem. Gyang dah ‘ngang sông’. Gyang mbaek haeux ‘lưng ống gạo’.

179. (V) ngáy [ŋăi5]. Tiếng phát ra từ miệng và mũi trong khi ngủ. Đêm nằm thì ngáy kho kho. <> (Z) gyaen [kjan1]. De ninz gyaen foxfox ‘Nó ngủ ngáy pho pho’.

180. (V) ngắc [ŋak7]. Ngúc ngắc: lắc qua lắc lại, ngúng ngẩy. <> (Z) ngak [ŋa:k7]. Ngucngak : ngúc ngắc. Ndaek neix caen ngukngak ‘Cô ta cứ ngúng nguẩy hoài’.

181. (V) ngăm [ŋam1]. Màu da hơi đen. Nước da bắt nắng ngăm ngăm đen. <> (Z) gyaemx [kjam4]. Idem. Ndaem gyaemx ‘đen thui’.

182. (V) ngắn [ŋan5]. Trường độ ít, trái với dài. Bóc ngắn cắn dài. <> (Z) gaenq [kan5]. Idem.

183. (V) ngắt [ŋat7]. Cảm giác lạnh lẽo, vắng vẻ. Lạnh ngắt. Vắng ngắt. Ngàn dâu xanh ngắt một màu. <> (Z) gyaet [kjat7] / gaet [kat7]. Buốt lạnh. Gij raemx neix gyaet lai ‘Nước chỗ này lạnh lắm’. Raemx gaet ‘Nước lạnh ngắt’.

184. (V) ngậm [ŋɤ̆m6]. Khép miệng. Giữ thức gì trong miệng và khép môi lại. Ngậm như miệng hến. Ngậm bồ hòn làm ngọt. <> (Z) iemj [i:m3] / iem [i:m1]. Idem. Iemj sae ‘hến ngậm miệng’. Bak iem raemx ‘Miệng ngậm nước’.

185. (V) nghĩ [ŋi4]. Suy xét. Tưởng nhớ đến. Nghĩ người ăn gió nằm sương xót thầm. <> (Z) ngeix [ŋei4]. Idem. Ngeix boh meh aencingz ‘Nhớ tới công ơn bố mẹ’.

186. (V) nghiêng [ŋieŋ1]. Theo chiều xiêu xiên, ngả sang một bên. Vành nón che nghiêng. <> (Z) ngeng [ŋe:ŋ1]. Idem. Ninz ngeng ‘nằm nghiêng’ . Hwnq saeu mboj ndaej ngeng ‘Dựng cột đừng để nghiêng’.

187. (V) ngòm [ŋɔm2]. Màu đen đục ngầu. Đen ngòm. <> (Z) hoemz [hom2].Đục ngầu. Raemx hoemz ndei lumh bya ‘Nước đục dễ mò cá’.

188. (V) ngon [ŋɔn1]. Hợp khẩu vị, khoái khẩu. Ăn ngon mặc đẹp. <> (Z) ngonz [ŋo:n2]. Idem. Gin ngonz lai ‘Ăn ngon quá’.

189. (V) ngốc [ŋokp7]. Ngu si, đần độn. Khôn độc, ngốc đàn. <> (Z) huk [huk7]. Idem. Boux huk ‘thằng ngốc’.

190. (V) ngốn [ŋon5]. Nuốt lấy từng miếng to. <> (Z) gyan [kja:n1]. Idem. Gyan gwn ‘Ngốn lấy ngốn để’.

191. (V) ngụm [ŋum6]. Chỗ nước được hớp uống một lần. Cho xin ngụm nước. <> (Z) gaemz [kam2]. Idem. Gwn song gaemz raemx ‘Uống vài ngụm nước’.

192. (V) nhai [ɲai1]. Dùng răng nghiền thức ăn trong miệng. Tay làm hàm nhai. <> (Z) nyaij [ɳa:i3]. Idem.

193. (V) nhánh [ɲɛɲ5] / nhành [ɲƐɲ2]. Cành cây nhỏ. <> (Z) ngingh [ŋiŋ6] / nyingh [ɳeiŋ6]. Idem. Yaeb nyingh faex guh fwnz ‘Nhặt những nhành cây làm củi đun’.

194. (V) nhắm [ɲăm5]. Nhai nếm thức ăn. Nhắm rượu. <> (Z) nyaemq [ɳam5]. Idem. Nyaemq laeuj ‘nhắm rượu’.

195. (V) nhặng [ɲaŋ1]. Ruồi xanh. <> (Z) nyaen [ɳan1]. Idem.

196. (V) nhắp [ɲap7]. Nhắm mắt, chợp mắt. <> (Z) laep [lap7]. Idem. Laep da cix raen lwnz ‘Vừa chợp mắt đã thấy bóng em’.

197. (V) nhặt [ɲăt8]. Chật, dồn, mau gấp. Bắt khoan bắt nhặt. <> (Z) nyaed [ɳat8]. Idem. Vunz nyaed lai ‘người chật rồi’. Nyaed fwnx haeuj cauq ‘Đun đầy củi vào lò’.

198. (V) nhấm [ɲɤ̆m5]. Gặm từng tí và nhai kỹ. Giám nhấm quần áo. <> (Z) nyaemj [ɳam3] / yaemj [jam3]. Idem.

199. (V) nhíp [ɲip7]. Khâu chắp lại. <> (Z) nyib [ɳip8]. Idem. Nyib buh moq ‘khâu áo mới’.

200. (V) nhỏ [ɲɔ3]. Bé, trái với “to”. <> (Z) nyoj [ɳo3]. Thu bé lại.

201. (V) nói [nɔi5]. Phát ngôn thành lời, trò chuyện. Miệng nói tay làm <> (Z) naeuz [nau2]. Idem. Dingq coenz vah mwngz naeux ‘Nghe lời mày nói’.

202. (V) óc [ɔkp7]. Bộ não. Nghĩ nát óc. <> (Z) uk [uk7]. Idem. Uk gyaeuj ‘đầu óc’.

203. (V) ôm [om1]. Quàng tay giữ chặt vào lòng. Ôm rơm nhặm bụng. <> (Z) umj [um3]. Idem. Umj lwg ‘Ôm em bé’.

204. (V) phô [fo1]. Bày ra, khoe ra. Có vàng, vàng chẳng hay phô. <> (Z) boq [po5]. Khoe khoang. Gangj boq ‘nói phét’.

205. (V) phồng [foŋm2]. Phình to lên. Phập phồng. <> (Z) bongz [po:ŋ2]. Idem. Dungx bongz ‘Bụng căng phồng lên’.

206. (V) phừng [fɯŋ2] / bừng [bɯŋ2]. Rực sáng lên. Lửa chợt bốc lên. Lửa cháy phừng phừng. Bừng sáng. <> (Z) foengx [foŋ4]. Idem. Cawj byaek aeu feiz foengx ‘Luộc rau lửa phải bốc mạnh’.

207. (V) quạ [kwa6]. Loài chim lông đen. Diều tha, quạ mổ. <>(Z) ga [ga1]. Lamjbwn roeg ga duzduz ndaem ‘Khắp nơi quạ đều đen như nhau’.

208. (V) quảy [kwai3]. Gánh một bên, bên còn lại tì tay cho cân bằng. Quảy thúng đi mua thóc. <> (Z) gvaij [kwa:i3]. Idem.

209. (V) quanh [kwɛɲ1]. Bốn bề. Vòng quanh. <> (Z) gvaengx [kwaŋ4]. Idem. Seiq gvaeng ‘chung quanh’.

210. (V) quăng [kwaŋ1]. Vứt đi. Vung ra xa. Bủa lưới quăng chài. <> (Z) gveng [kwe:ŋ1]. Idem. Gveng roengz daemz bae ‘Vứt xuống ao cho rồi’.

211. (V) què [kwɛ2]. Chân bị tật, khó đi. Gà què ăn quẩn cối xay. <> (Z) gvez [kwe2]. Idem. Ga gvez ‘chân què’.

212. (V) quét [kwɛt7]. Dùng chổi làm sạch rác. Con sãi ở chùa thì quét lá đa. <> (Z) gvet [kwe:t7]. Idem. Gvet nyapnyaj ok bae ‘Quét cho sạch rác đi’.

213. (V) rám [ʐam5]. Nắng hoặc lửa thiêu cho đỏ hoặc đen đi. / sạm [şam6]. Đen sẫm lại. Da rám nắng mà sạm đen. <> (Z) ramj [ɣa:m3]. Đốt cháy. Gaej gwn ngaiz haue ramj ‘Đừng ăn cơm đã cháy đen’.

214. (V) ràng [ʐaŋ2]. Dùng dây quấn buộc xung quanh. Ràng buộc lấy nhau. <> (Z) rangh [ɣa:ŋ6] / riengh [ɣi:ŋ4]. Nối với nhau. Rangh cieg ‘nối dây thừng’. Lumj maesei dox riengh ‘Dường như dây tơ chắp nối’.

215. (V) rêu [ʐeu1]. Loài tảo mọc nơi ẩm ướt (chân tường, vách đá). Hòn đá xanh rì lún phún rêu. <> (Z) reuz [ɣeu1]. Idem. Byaek reuz cauj noh ‘Quơ rêu nướng thịt’.

216. (V) riu [ʐiu1]. Đồ đan để xúc bắt tép. Đi riu tép. Tép riu. <> (Z) yiuz [ji:u2]. Loài tôm nhỏ, tép.

217. (V) rò [ʐɔ2]. Nước rỉ ra ngoài. Nước rò ra từ chân đê. <> (Z) roh [ɣo6]. Idem. Fwn doek ranz cix roh ‘Vừa mưa mái nhà đã dột’.

218. (V) rõ [ʐɔ4]. Hiểu ra, nhận thấy được. Hai năm rõ mười. <> (Z) rox [ɣo4]. Idem. Mwngz rox mbouj rox ‘Mày đã rõ hay chưa rõ’.

219. (V) rộc [ʐokp8]. Ruộng ở khe núi. <>(Z) lueg [lu:k8]. Idem.

220. (V) rống [ʐoŋm5]. Tiếng kêu của động vật to. Tiếng chó sủa, tiếng trâu rống. <> (Z) rongx [ɣo:ŋ4]. Idem. Vaiz rongz ‘trâu rống’. Guk rongz ‘hổ gầm’.

221. (V) rộng [ʐoŋm6]. Có kích cỡ lớn, sức chứa nhiều. Hai ống quần rộng thùng thình. <> (Z) loengz [loŋ2]. Idem. Geu buh neix loengz lai ‘Bộ áo quần này rộng quá’.

222. (V) rốt [ʐot7]. Cuối chót. Một trai con thứ rốt lòng. <> (Z) yot [jo:t7]. Idem. Boh meh gyaez lwg yot ‘Bố mẹ cưng chiều con út’.

223. (V) rưới [ʐɯɤi5]. Rách rưới: quần áo cũ nát, tơi tả. Rách rưới như gã ăn mày. <> (Z) lwiz [lɯ:i2]. Cũ nát. Vaj lwix ‘mảnh vải cũ’.

224. (V) sao [şa:u1]. Tinh tú trên trời. Trông cá cá lặn, trông sao sao mờ. <> (Z) ndau [da:u1]. Idem. Ndau gwnz mbwn ‘sao trên trời’.

225. (V) sàng [şaŋ2]. Đồ đan bằng nan tre, có lỗ (thưa hơn dần) để làm sạch gạo sau khi xay thóc. Công em xay giã dần sàng. <> (Z) raeng [ɣaŋ1]. Idem. Ndaw ranz raeng mbouj lad ‘Trong nhà dần sàng đều chẳng có’.

226. (V) sai [şai1]. Nhiều, dày đặc (quả). Vườn cam sai quả. <> (Z) seiq [θe:i5]. Nhiều, đông đúc. Aen mbanj neix vunz seiq ‘dân cư bản này thật đông đúc’.

227. (V) sém [şɛm5]. Bị bắt lửa cháy ở rìa hoặc bề mặt. <> (Z) remj [ɣe:m3]. Quá lửa cháy khô. Cawj byaek remj loh ‘Rau nấu bị cháy sém rồi’.

228. (V) sét [şɛt7]. Hiện tượng phóng điện giữa mây và mặt đất, gây tiếng nổ to. Giữa đường mụ bị sét đánh chết <> (Z) deg [te:k8]. Idem.

229. (V) soi [şɔi1] / rọi [ʐɔi6]. Chiếu sáng. Ánh trăng soi sáng muôn nơi. Ngọn đuốc rọi thẳng vào hang. <> (Z) coij [ɕo:i3]. Idem. Ndit coij ‘Ánh nắng chiếu rọi’.

230. (V) suối [şuoi5]. Khe nước trong rừng. Dòng suối nhỏ chảy ra sông. <> (Z) guij [khu:i3]. Idem.

231. (V) sượng [şɯɤŋ6]. Củ luộc rồi mà chưa thật chín, hoặc không mềm. Sắn này không bở, sượng lắm. <> (Z) swnx [θɯn4]. Idem. Aen sawz neix lij swnx ‘Khoai này sượng lắm’.

232. (V) tày [tăi2]. Kiểu chào ngày xưa, hai bàn tay úp lên nhau, hơi nâng cao và đưa về phía trước. Ngươi Trung Ngộ rảo đến trước tày rằng. <> (Z) sax [θa4]. Idem.

233. (V) tăm [tăm1]. Bọt khí trong nước. Sông dài cá lội biệt tăm. <> (Z) cimq [ɕim5]. Idem.

234. (V) tí [ti5]. Một chút. Đợi một tí. <> (Z) deij [tei3]. Idem. Mwng byaij heih deij ‘Mày mau mau lên một chút’.

235. (V) thét [thɛt7]. Kêu to, quát to. Gào thét vang trời. <> (Z) sek [θe:k7]. Idem. sek vaiz ‘Thét mắng con trâu’.

236. (V) to [tɔ1]. Có kích cỡ lớn. Lớn mật to gan. Tai to mặt lớn. <> (Z) daeu [tɑu1]. Idem.

237. (V) tơi [tɤi1]. Áo chằm bằng lá, mặc che mưa. Mang tơi đội nón ra đồng. <> (Z) se [θe1]. Idem.

238. (V) trai [tʂai1]. Người thuộc giới nam. Một trai con thứ rốt lòng. <> (Z) sai [θa:i1]. Idem. Boux sai ‘đàn ông’.

239. (V) trái [tʂai5]. Bên tả, ngược với bên phải. Nó thuận tay trái. <> (Z) soix [θo:i4] / swix [θɯ:i4]. Idem. Mungz soix ‘tay trái’. Fwngz swix ‘tay trái’.

240. (V) tro [tʂɔ1] / gio [zɔ1]. Tàn than còn lại sau khi cháy. Bôi tro trát trấu vào mặt. <> (Z) gyoq [kjo6]. Idem. Gyoq feiz ‘tro tàn’.

241. (V) tròn [tşɔn2]. Hình phẳng hoặc hình khối khép vòng, không có cạnh. Yêu nhau trái ấu cũng tròn. Đêm rằm trăng tròn. <> (Z) luenz [lu:n2]. Idem. Luenz lujluj ‘tròn vành vạnh’.

242. (V) trống [tşoŋm5]. Nhạc cụ làm bằng gỗ (tang trống), hai đầu bịt da (mặt trống). Tùng tùng trống đánh ngũ liên. <> (Z) gyong [kjo:ŋ1]. Idem. Aen laz baengh aen gyong ‘Tiếng cồng phải hòa với tiếng trống’.

243. (V) trơn [tşɤn1]. Bề mặt có độ ma sát thấp, dễ trượt. Trời mưa đường đất trơn như mỡ. <> (Z) conj [ɕo:n3]. Trượt. Conj roengz ‘trượt xuống’ / lwenq [lɯ:n5]. Trơn bóng. Gwnz rin gig lwenq ‘Mặt đá thật trơn’.

244. (V) trùm [tşum2]. Bao phủ lên trên. Bóng cây trùm mái nhà. <> (Z) gyuem [kju:m1] / rumj [ɣum3]. Idem. Haemh ninz yaek gyuem denz ‘Đêm ngủ phải đắp chăn’.

245. (V) ức [ɯk7]. Phần ngực của loài chim, thú. Con gà chân cao, ức nở. <> (Z) aek [ak7]. Ngực. De enj aek dwk byaij ‘Nó ưỡn ngực mà đi’.

246. (V) ưỡn [ɯɤn4]. Vươn ngực lên phía trước. <> (Z) enj [e:n3]. Idem. De enj aek dwk byaij ‘Nó ưỡn ngực mà đi’.

247. (V) ửng [ɯŋ3]. Hơi đỏ lên. Đôi má ửng hồng / hửng [hɯŋ3]. Hơi sáng lên. Trời hửng nắng <> (Z) wenj [ɯ:n3]. Trời quang tạnh. Trời rực sáng. Mbwn wemj ‘trời tạnh’. Daeng ngoenz wenj vangjvangj ‘Trời nắng rực rỡ’.

248. (V) vác [vak7]. Đặt đồ lên vai mang đi. Nhà nông vác cuốc ra đồng. <> (Z) mbeg [be:k8]. Idem.

249. (V) vai [vai1]. Phần cơ thể giữa cổ và cánh tay. Lưng dài vai rộng. Áo vắt vai, quần hai ống ướt. <> (Z) mbaq [ba5]. Idem. Rap dwk mbaq hwnj daw ‘Gánh nhiều vai chai cả đi’.

250. (V) vải [vai3]. Vật liệu để may áo quần, dệt từ sợi bông. Mà nay áo vải cờ đào <> (Z) baix [pha:i4]. Idem.

251. (V) vẩy [vɤ̆i3]. Vung vẩy: bàn tay cử độmg liên tục . Chó vẩy đuôi mừng. <> (Z) vae [wai1]. Idem.

252. (V) vẹo [vɛu6]. Nghiêng lệch sang một bên. Dáng đi xiêu vẹo. <> (Z) mbeuj [be:u3]. Lệch, không ngay ngắn. Naengh mbeuj loh ‘Ngồi lệch rồi’. Faex mbeuj gawq mbouj baen benj ‘Gỗ cong vẹo không xẻ thành ván được’.

253. (V) vịt [vit8]. Loài gia cầm bơi trên nước. Khách đến nhà, không gà thì vịt. <> (Z) bit [pit7] / baet [pat7]. Idem.

254. (V) vứt [vɯt7]. Ném đi, quăng đi. Vứt tiền qua cửa sổ. <> (Z) vut [wut7]. Idem.

255. (V) xiên [sien1]. Nghiêng chéo một bên. Ánh nắng chiếu xiên xuống sân. <> (Z) cienx [ɕi:n4]. Idem. De byaij ngauz cienx cienx ‘Nó đi dáng xiêu vẹo’.

256. (V) xổ [so3] / sổ [ʂo3]. Thoát ra, buông ra, tháo ra. Con sáo sổ lồng. <> (Z) coq [ɕo5]. Buông, thả, tháo. Coq haeux roengz rek ‘Bỏ gạo vào nồi’. Haemh neix gou bae coq raemx ‘Tối nay tôi đi tháo nước vào ruộng’.

257. (V) xống [soŋm5]. Quần, váy. Áo xống. <> (Z) congz [ɕo:ŋ2]. Bộ (áo quần). Daenj congz buh ndeu ‘Mặc bộ quần áo’.

3. General Observations

1. Most of the Vietnamese and Zhuang morphemes listed above correspond on a one-to-one basis. However, in some cases, one form in one language may correspond to two or three forms in the other. Such coexisting forms may represent cognates that have undergone slight semantic shifts, or they may simply be phonetic variants.

2. The majority of the Vietnamese and Zhuang morphemes considered here are monosyllabic and can be used independently in sentences. Nevertheless, there are cases where a morpheme is monosyllabic and independent in one language, while in the other its counterpart is not an independent morpheme (often appearing only in reduplicated forms).

3. The phonological correspondences between common Vietnamese and Zhuang morphemes are highly diverse and complex, reflecting different historical layers of linguistic development. Leaving aside tone and rhyme correspondences, we may make a preliminary comparison of the relationship between initial consonants in the two languages. Based on the data presented above, a few observations may be noted:

a. There is an almost complete one-to-one correspondence for the Vietnamese initials l [l-], m [m-], and n [n-] with Zhuang. However, viewed from the Zhuang side, there are slight divergences: three Zhuang morphemes with initial l [l-] correspond respectively to Vietnamese nh [ɲ-], r [ʐ-], and tr [tʂ-].

b. Some Vietnamese initials correspond primarily to a limited number of initials in Zhuang. For example:

- (V) b [b-] <> (Z) mainly b [p-], mb [b-]; occasionally f [f-].

- (V) c/k/q [k-] <> (Z) mainly g [k-]; occasionally c [ɕ-], r [ɣ-].

- (V) ch [c-] <> (Z) mainly c [ɕ-]; occasionally y [j-], r [ɣ-], gy [kj-].

- (V) đ [d-] <> (Z) mainly d [t-]; occasionally nd [d-].

- (V) g [ɣ-] <> (Z) mainly g [k-], r [ɣ-]; occasionally g- [kh-], ng [ŋ-].

- (V) h [h-] <> (Z) mainly h [h-]; occasionally g [k-], or zero [∅-].

- (V) zero [∅-] <> (Z) mainly zero [∅-]; occasionally h [h-].

(In the data presented above, zero-initial [∅-] has been omitted for convenience.)

Other Vietnamese initials exhibit more scattered correspondences with Zhuang initials and are not listed here.

The data and general observations presented here are, of course, not yet exhaustive. They may still require correction and supplementation with additional materials.

References

- de Rhodes, Alexandre. Từ điển Annam-Lusitan-Latin. Roma, 1651. Bản dịch tiếng Việt của Thanh Lãng, Hoàng Xuân Việt, và Đỗ Quang Chính. Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh: Nxb Khoa học Xã hội, 1991.

2. 古壯字字典 (Sawndip Sawdenj), sơ cảo. Quảng Tây: Quảng Tây Dân tộc Xuất bản Xã, 1989.

3. Hoàng Phê, chủ biên. Tự điển tiếng Việt. 7th ed. Hà Nội – Đà Nẵng: Nxb Đà Nẵng – Trung tâm Từ điển học, 2000.

4. Huình Tịnh Của. Đại Nam quấc âm tự vị (Dictionarie Annamite). Saigon, 1895 (tập I); 1896 (tập II).

5. Nguyễn Quang Hồng, chủ biên. Tự điển chữ Nôm (Sơ thảo). Hà Nội: Nghiên cứu Hán Nôm, 1995.

6. Nguyễn Quang Hồng. “Hiện tượng đồng hình giữa chữ Nôm Việt và chữ vuông Choang.” Tạp chí Hán Nôm, no. 2 (1997).

7. Nguyễn Tài Cẩn. Giáo trình lịch sử ngữ âm tiếng Việt (Sơ thảo). Hà Nội: Nxb Giáo dục, 1995.

8. 张公谨 等著. 民族古文献概览. 北京: 民族出版社, 1997.

9. 张元生 等编. 古壯字文献迭註. 天津: 天津古籍出版社, 1992.

10. 徐松石. 傣族 撞族 越族 考. In 民族学研究著作五种 (上). 广东: 广东人民出版社, 1993.

11. 王力. 同源字典. 北京: 商務印書舘, 1982.

Note: This article by Prof. Dr. Sci. Nguyễn Quang Hồng was originally presented as a report at the 5th Southeast Asian Linguistics Conference, Ho Chi Minh City, 2000. It was later published in the journal Ngôn ngữ (Language), 2001, no. 13. We have received the author’s permission to republish this article on the Digitizing Vietnam website.

Chữ Nôm constitutes a salient phenomenon in the historical development of Vietnamese culture. In essence, it is a script that appropriated the graphic forms and principles of character construction from the Chinese writing system to transcribe the Vietnamese language—yet in doing so it embodied a remarkable degree of indigenous creativity.

A question long debated by scholars is: when did Chữ Nôm first emerge? Some suggest that as early as the beginning of the Common Era, with the introduction of Chinese script into Vietnam, isolated “Nôm” graphs were created to represent local toponyms, personal names, and native products, inserted sporadically into Chinese texts. However, this does not imply that Nôm, as a coherent logophonetic system for Vietnamese, was already in existence at that time. The transformation from scattered, provisional characters to a structured and functional script was a protracted process. On the basis of extant research, it is now generally accepted that by the Trần dynasty (13th century), Nôm had achieved the status of a recognizable writing system with the capacity for independent use.

Familiar Yet Unfamiliar

Readers literate in Chinese often assume, at first glance, that they can easily comprehend a Nôm text. Closer examination, however, reveals their surprise at finding it largely unintelligible. This paradox stems from the fact that while Nôm characters retain the outward form of Chinese graphs, their modes of construction are uniquely innovative. Beyond conventional methods such as semantic–phonetic compounding, Nôm also employs associative principles, semantic linkages, and what scholars have termed “submerged–emergent” structures, which defy the expectations of readers trained only in Chinese.

The Structure of Chữ Nôm – Some ‘Keys’ to Decipherment

Scholarly inquiry into the structure of Nôm has yielded various classificatory schemata. Rather than rehearse these in detail, it is useful to underscore several critical insights.

Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng distinguishes between “Nôm giả tá”—instances where Chinese characters were borrowed wholesale or with only minor phonetic shifts, which need not concern structural analysis—and those instances where characters were adapted or created with modification. In such cases, structural analysis becomes essential. Examples include reduction, as in the character Một 殳, traced to 没 but with a component elided; and augmentation, as in Đĩ 𡚦, created by adding a dot to the graph 女 (“woman”).

Even more complex are characters created through phonetic amalgamation. Such characters have no precedent in Chinese and epitomize Nôm’s distinctiveness. As Nguyễn Quang Hồng notes, these include:

Phonetic compounds (hội âm): characters combining two phonetic elements, e.g. Trăng/Giăng < blăng 𢁋 (巴 ba + 陵 lăng), Trước 𨎟 < klươc (略 lược + 車 cư), reflecting the preservation of complex consonant clusters (bl, ml, tl) in Vietnamese prior to the seventeenth century.

Radical assignment by associative linkage: some characters exhibit radicals that seem semantically incongruous unless viewed relationally. For example, Lỡ (𧾷+呂) in the line “Tối tăm lỡ bước đến đây” (Lục Vân Tiên) gains explanatory force only when juxtaposed with the following character Bước 𨀈 (𧾷+北). Similarly, the use of the “shell” radical 貝 in Gần 𧵆 becomes intelligible only in its semantic pairing with Xa 賒, which itself carries the radical 貝.

Submerged–emergent structures: certain characters conceal part of their phonetic basis, leaving visible only partial indicators. For instance, variants of Mười/Mươi (𨒒, 辻, 𨑮) contain the radical ⻍ (“walk”), traceable to the fuller phonetic base 迈 (mại). Here, the overt (emergent) structure coexists with an implicit (submerged) structure, a duality crucial for understanding the logic of Nôm character formation.

Such phenomena reveal both the structural “instability” of Chữ Nôm and, at the same time, the ingenuity, adaptability, and resourcefulness of its users. By situating these characters within broader networks of phonetic, semantic, and contextual associations, one gains access to the interpretive keys necessary for engaging with Nôm texts.

Thus, the study of Chữ Nôm not only illuminates the inventive capacities of Vietnamese literati but also demonstrates how local cultural agency appropriated and transformed foreign models into a distinctive script responsive to the phonological and semantic demands of the Vietnamese language.

(Based on “Some Issues and Aspects of the Study of Nôm” in the collected volume Language. Script. Literature by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng)

On the afternoon of October 7, 2025, Prof. Dr.Sci. Nguyễn Quang Hồng—who devoted his life to the studies of the Vietnamese language and the Hán–Nôm heritage—passed away, entering the vast silence beyond all language.

To the Professor, time—time lived—was the precious condition that made possible his reflections on that singular human invention: language. "The author sat at his desk and typed this monograph for more than a year. Yet the period during which he pursued the questions posed in the work adds up to over twenty years,” he confides in the preface to An Introduction to the Grammatology of Chữ Nôm, recalling his tireless pursuit of the great questions of Vietnamese and its writing. That unceasing research journey crystallized into major works gathered in the collection Language · Writing · Philology on Digitizing Vietnam—only “the tip of the iceberg,” layered over decades of reflection, investigation, and painstaking scholarly labor: concerns ranging from system to detail, from phonetics to literature, from antiquity to the present—all to reach the uttermost of the Vietnamese story.

In his scholarly rigor, the author rarely spoke about himself. The long, winding road—surely with many rough stretches—into the “uttermost ends” of the Vietnamese language is summed up by him in two sentences: “The author is a linguist who, together with linguistics, entered the study of Chữ Nôm and Hán–Nôm texts and works. Viewed in general, then, the author is someone passionately devoted to the work of our national philology.”

Prof. Dr.Sci. Nguyễn Quang Hồng was born in 1940 in Trà Kiệu village, Duy Xuyên district, Quảng Nam province. 1960–1965: studied in Beijing, graduated B.A. in Philology (Peking University, 1965). 1970–1974: graduate studies in Moscow; defended the Candidate of Philological Sciences (Moscow State University & the USSR Institute of Oriental Studies, 1974). 1982–1985: research fellow; defended the Doctor of Philological Sciences. He was appointed Associate Professor in 1984 and Professor in 1991.

The Language · Writing · Philology collection brings together Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng’s studies in linguistics, scriptology, and philology. Among them, Vietnamese Syllables and Poetic Language is a monograph co-authored with Dr. Phan Diễm Phương. The studies are diverse, spanning many phenomena and problems, and can be grouped into two main strands: (1) Linguistics and Vietnamese language studies; (2) Philology and Hán–Nôm studies. Digitized items in Digitizing Vietnam’s repository include:

❃ Syllables and Types of Language

❃ Language · Writing · Philology

❃ An Introduction to the Grammatology of Nôm

❃ Explanatory Notes on Truyền kỳ mạn lục

❃ Vietnamese Syllables and Poetic Language

❃ The Inscriptions of Dâu Pagoda: Cổ Châu lục – Cổ Châu hạnh – Cổ Châu nghi

SKETCHING A PORTRAIT OF VIETNAMESE IN LINGUISTICS: WHEN LINGUISTIC SENSIBILITY GUIDES SCIENTIFIC THOUGHT

Looking at Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng’s linguistic work on Vietnamese, we see not only weighty findings with wide interdisciplinary impact, but also a meticulous comparative program tracking movements within a language and across languages to find the right “frame” for analyzing Vietnamese. Alongside broad engagement with existing models is a guiding “linguistic sensibility”—a keen effort to reconstruct, scientifically, the inner psycholinguistic reality, rather than mechanically imposing a fashionable model.

From this foundation, he established that the tone-bearing syllable (syllabeme) is the minimal meaning-bearing unit of modern Vietnamese; the syllable’s structure is viewed as onset – rime (rime = nucleus + coda), while tone and the medial glide are properties of the whole syllable. Within this framework he situated Vietnamese in a comparative–typological context with other tone languages of East and Southeast Asia (Việt–Mường, Tai–Thai, Sinitic, Tibetic…), treating the syllable as central and analyzing in detail onset – rime – tone; he also bridged phonology and poetics, using verse (especially The Tale of Kiều) to test rhyme, distinguish full rhyme/allowable rhyme, and explain the aesthetic of “harmonious sound.”

In comparison with Chinese, he showed that intra-syllabic segmentation is clearer in modern Vietnamese (and Middle Chinese) than in modern Beijing Mandarin. Vietnamese is rich in reduplication (nhí nhảnh, bồi hồi…) and metathesis/wordplay; Middle Chinese had a comparable phenomenon (“fanqie-like manipulations”), whereas modern Beijing Mandarin tends toward full-syllable repetition (mànmànr, lànlànde), reducing intra-syllabic variation. Reading the Professor’s meticulous comparisons, one seems to step into a linguistic laboratory where diverse syllables are dissected and set in motion under the absorbed gaze of a scientist.

RESEARCH ON CHỮ NÔM: CONNECTING WITH THE WISDOM AND HEART OF GENERATIONS

One cannot speak of Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng without the now-classic studies of Chữ Nôm, such as An Introduction to the Scriptology of Chữ Nôm and the Explanatory Dictionary of Chữ Nôm.

An Introduction to the Scriptology of Chữ Nôm is a foundational work treating Nôm through historical linguistics – comparative scriptology – textual scholarship. It establishes a basic conceptual toolkit (language/script; tục tự, thổ tự, phương tự; “non-standard” Chinese characters; what “Chữ Nôm” is), situates Nôm within Vietnam’s traditional scripts (Cham, Thai; Dao Nôm, Ngạn Nôm, Tày Nôm…), and traces the origins and conditions of Nôm through Việt–Sinitic contact, Sino-Vietnamese readings, Lý-dynasty epigraphy, and hypotheses about its emergence. On that basis, he presents the Chinese character model (structure, formation, morphemes), contrasts typological traits of Nôm with other Sinitic-based scripts, distinguishes borrowed Chinese characters from Nôm creations, and proposes a general classification for Vietnamese Nôm.

The Explanatory Dictionary of Chữ Nôm marks a major advance in the study and explication of Nôm, illuminating the creativity and self-reliant spirit of the Vietnamese in language. Based on 124 classical works/texts, each entry has clear provenance with contextual examples.

“By engaging with the Hán–Nôm heritage, we simultaneously engage with the intellect and the heart of countless generations of our forebears across every sphere of our country’s social life in the past.”

The Professor emphasized: “Language—and with it, script—is not merely a vehicle for transmitting information, but a vehicle for transmitting culture, especially from one generation of the nation to the next.”

For him, researching Chữ Nôm was not only a scholarly passion but also a connecting mission, so that generations of Vietnamese might feel the intellect and singular creativity of their ancestors beyond the bounds of time.

SOLVING EVERYDAY RIDDLES WITH SCHOLARLY WIT: THE SHORT i AND THE LONG y

Alongside academic works, Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng wrote with humor and grace about everyday language puzzles. A widely loved essay is the story of the short i and the long y. It began with a letter from a technician who types on-screen text for Bình Thuận Television. Unsure whether to write công ti or công ty (“company”)—the director said one thing, the department head another—he asked if there was a rule.

A small matter that isn’t small: Prof. Nguyễn Quang Hồng answered in detail—over four pages—patiently moving from Ministry of Education rules (a syllable ending in the vowel i is written with i, except after u/y as in duy, tuy, quy) to conventions formed over centuries (long y in Sino-Vietnamese words; short i in native words). For the technician’s question, the Professor refused to clamp Vietnamese into a rigid right/wrong vise; instead he showed the calm vision of a scholar who has gone deep enough into the language to trust its resilient flexibility:

“I think that in actual writing practice we should not be too rigid, insisting on applying at once what has been propagated in school. Moreover, what we have learned in school must be tested in social reality; only then can we find more appropriate standards that we hope will be accepted by everyone. If necessary, I am also ready to write ‘công ty’ to suit the ‘taste’ of your supervisor—which may also be the wish of the company that is your agency’s partner!”

He also gently corrected the writer for qui định instead of quy định (“regulation”): “As for quy, I don’t understand why you follow some others in writing qui. Granted, whether you write quy or qui you still pronounce it q + uy, but writing with -ui veers off from the series of words that all rhyme in -uy: duy, huy, luy, tuy, suy, nguy, etc.” The rigor of the linguist led him to catch an “error” not against external rules but against the internal dynamics of the language. “In this case—even if my boss threatened to dock my pay or fire me—I would still write Quy, and would by no means ‘shorten’ it to Qui, mind you,” he quipped—reminding the technician to safeguard Vietnamese, signing off with the colloquial đâu nghe (“mind you”) like a gentle word to a friend. In the stately pages of Language · Writing · Philology, that letter and those two words seem to reveal another face of the author—warm, familiar, simple: a Vietnamese who loves Vietnamese.

The “patchwork rustic words” above can hardly capture the roving dedication of Prof. Dr.Sci. Nguyễn Quang Hồng—a man who went to the farthest reaches of language, touching the finite frontier of a human life. Recall the word “hundred years” in Kiều’s line “Trăm năm trong cõi người ta,” meaning a human lifetime in this world: the character “hundred” (bách 百) set beside lâm 林—the finite beside the infinite. Digitizing Vietnam hopes to join readers in connecting with this finite collection and to grant the work a new “hundred years” of life—to carry the finite toward the infinite.

👉 Read the Language · Writing · Philology Collection:

https://www.digitizingvietnam.com/vi/our-collections/ngon-ngu-van-tu-ngu-van

👉 Read Tự điển Chữ Nôm Dẫn giải:

https://www.digitizingvietnam.com/vi/tools/han-nom-dictionaries/tu-dien-chu-nom-dan-giai

❀ Our deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr.Sci. Nguyễn Quang Hồng (1940–2025) for the legacy he leaves to posterity.